Literary Sex Change, Using a Male Pseudonym

Rosemary Friedman has published more than 26 titles, initially under a male pseudonym. She explains to WWWB what made her decide to do so.

Rosemary Friedman has published more than 26 titles, initially under a male pseudonym. She explains to WWWB what made her decide to do so.

Literary Sex Change, Using a Male Pseudonym

On the 13th of November 1956, having tentatively sent my first novel, No White Coat, to mainstream publisher Hodder & Stoughton I received the following letter (no email then).

`We have safely received the typescript of your novel and will give it a careful reading. We hope however that you will not be too disappointed if we have to decide that we cannot make you an offer for its publication, as our lists are so full for many months to come that we have to be extremely selective in adding to them.’

I heard nothing more until February 5th (my birthday) 1957. Hodder & Stoughton liked my novel for its qualities of `kindness, feeling and humour’ and enclosed a Memorandum of Agreement to publish it. I had submitted the manuscript under a male pseudonym and the covering letter, from the chairman of the firm, Ralph Hodder-Williams, was addressed `Dear Sir’!

What led me to pass myself off as a man is a question frequently put. In No White Coat the male doctor’s account of his first year in general practice would, I thought, sound more authentic if the reader were to believe that the author and the narrator were one and the same.

There was another reason. Then, and to a lesser extent, now, many male readers would not deign even to pick up a book written by a woman which led me to consider whether women write differently from men and if there is really such a thing as a `woman’s book’.

As long ago as 600 BC Sappho and her contemporaries were turning out poetry on their Greek island, but from that time on – with certain notable exceptions – there was a deafening silence from female writers in England until the end of the 18th century. Given the fact that women at that time were not only denied education, but were frequently knocked about by their husbands, this is not surprising.

The circumstances were hardly favourable to creative expression. It was not until women had a little money, a little leisure, and, if they were lucky, the proverbial `room of one’s own’ that the well-springs were uncovered and the talent gushed forth. Was women’s situation apparent in their writing? Consider the following example:

`During the interval between dinner and the arrival of the guests, she felt as a young soldier feels before going into action. Her heart throbbed violently and she could not keep her thoughts fixed on anything.’

This passage was in fact written by Leo Tolstoy and his ability to write convincingly as a woman was echoed by Flaubert who had no difficulties in writing as both man and woman, both lover and mistress.

In adopting a male pseudonym it was not my intention either permanently to adopt a male persona or to deceive my readers.

I did not want to `change my sex’ without having the advantages of male writers such as Trollope who worked on Barchester Towers with a pencil then `…Rose made a copy in ink afterwards…’; Kipling whose household was taken over by Carrie Balestier to `protect’ him from visitors; or Anthony Burgess whose wife drove him round Europe while he got on with his novel in the back of the Dormobile.

My deception however was taken in good part by Hodder & Stoughton and was later exploited on a TV book programme when I was billed as `Robert Tibber’ and – unknown to me – the camera honed in on my ankles and worked its way upwards.

The use of pseudonyms by writers is as rich and varied as the history of literature itself. Every author has his or her own reason for adopting a pen name and there was a time when female writers were led to believe that it was their gender that prevented their work from being taken seriously.

The Bronte sisters, who started their writing life as Ellis, Acton and Currer Bell, had the impression that `authoresses are liable to be looked upon with prejudice’, while by using initials (not even her own as she has no middle name) J.K. Rowling bowed to her publisher’s belief that the Harry Potter books would not be as popular with boys if they realised that they had been written by a woman. Their subsequent success revealed that a woman doesn’t need a man’s name to set the literary world ablaze.

Perhaps the most successful example of literary sex change was that of Mary Ann Evans, more widely known as George Eliot, who used a male pseudonym in order to make sure that her work was validated and that she would not be written off as another `romantic novelist’.

In my own case, and with hindsight, adopting a male pseudonym was a rash and foolish decision. While Hodder & Stoughton encouraged me – for publicity purposes – to stick with Robert Tibber for subsequent books, especially those about my `doctor’, I felt increasingly fraudulent and uncomfortable and by the time my tenth novel The Life Situation was published I had resorted to my proper name and gender.

When the chips are down, however, it doesn’t really matter what name is used nor what arcane writing ritual is involved. The important thing is getting the words on to the paper at which point, as American newspaper columnist Robert Benchley succinctly put it, the writer will be paid `Per word, per piece, or perhaps.’

—

Rosemary Friedman has published 26 titles (including 3 non-fiction and 2 children’s books) several of which have been translated and serialised by the BBC. Her 50 short stories have been syndicated worldwide.

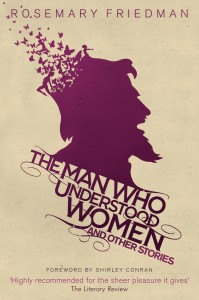

By her latest book, The Man Who Understood Women and Other Stories HERE

Visit her website www.rosemaryfriedman.co.uk and follow her on twitter @RFriedmanAuthor

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing, Women Writers

Comments (7)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post

- Harrison Ford, Literary Sex Change, & More! - Suzanna Linton | March 13, 2015

I always had mixed feelings about the concept of using a male pseudonym. While I’m happy that women writers (biggest example I can think of is J.K Rowling) can disguise their names with the intention of appearing to be a male writer and thus have a best selling series.. It’s sad that in our society a woman feels that they don’t have as good of a chance using their real name on the cover.

“Deafening silence from women until the 18th century”? You skip over Marie de France, who set the tone for the greater part of Arthurian fiction in the 12th century. She’s got that name because, while originally from France (Brittany) she’s living in England, probably in the court of Henry II. Her influence and popularity were strong.

It’s more oblique to argue for Margery Kempe, whose autobiography was written down by a month early in the fifteenth century, but Julian or Norwich was certainly dictating her own Showings in the late fourteenth century, her fame so strong that Margery made sure to visit her and get her blessing for her own unconventional life.

Outside England there were other women too, from Hildegard of Bingen to Christine de Pisan.

Apart from that, I would add that among my noms de plume is a male name, Graham Wynd, for noir writing as the readership and self-appointed poobahs are mostly male and seldom read (or lionise) women. It’s irksome.

For “month” read “monk” >_<

Extremely interesting article. I plan to write from the male perspective once my first novel is complete and I also plan to use my initials only – L.G so that people don’t know if I’m male or female. They can make their mind up as they read the book (if it’s ever in publication!).

Thanks for this thought provoking piece.

Great story Rosemarie, and I especially loved your walk through history. Thank you very much for sending this essay our way! – Anora McGaha, Editor

What an interesting perspective. I’ve always found in curious that Nora Roberts publishes under JD Robb. While not a male name, directly, I think it was used to blur the gender and be able to broaden the market. Of course, everyone now knows the duo name and accepts her books because they are fun reads.