Q&A with Marly Youmans

Marly Youmans is an award-winning writer, poet and the author of 13 books. Recent poetry books include a long narrative, THALIAD (“mesmerizing…a work of genius”–Lee Smith), and two collections, THE FOLIATE HEAD and THE THRONE OF PSYCHE.

Marly Youmans is an award-winning writer, poet and the author of 13 books. Recent poetry books include a long narrative, THALIAD (“mesmerizing…a work of genius”–Lee Smith), and two collections, THE FOLIATE HEAD and THE THRONE OF PSYCHE.

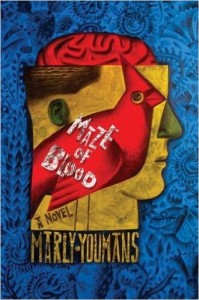

Her recent novels are GLIMMERGLASS (“resonant, beautiful”–Margo Lanagan) and A DEATH AT THE WHITE CAMELLIA ORPHANAGE (“controlled lyrical passion…the finest, and the truest period novel I’ve read in years”–Lucius Shepard), and most recently, MAZE OF BLOOD (September, 2015, Mercer House), which is based on the life of pulp fiction writer Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan the Barbarian. Maze of Blood is a Foreword Reviews’ 2015 INDIEFAB Book of the Year Award Finalist.

Youmans has been called the best kept secret among American Writers and is known for collaborating with other artists in the production of her books. Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ work figures prominently in her last two novels.

Marly lives in Cooperstown, NY where she and her husband have raised three children. She maintains an enchanting website called The Palace at 2 a.m. where she blogs about art, poetry, her books, and the magical power of words. We’re excited to welcome Marly to WomenWritersWomen[‘s]Books.

How did your upbringing influence your writing? What were your teen years like?

My parents were a librarian and an analytical chemist (he also wrote poetry and fiction), and we had lots of books. I’d just as soon not consider my teen years, though I was very happy when we moved back South when I was thirteen. (My three years in Delaware were demoralizing–that’s where a teacher thought me mentally deficient. That drawl, y’all!) But I wrote a great deal of poetry as a teen. And I’m still close to some of my friends from those years.

How did you decide on writing about Robert E. Howard? Are you a pulp fiction fan in general or was it something specific about his story?

The figure of Conall Weaver [protagonist] comes out of my desire to do something new every time I write a novel. I like to make something that I have never thought about making before, something that I will have to master in a new way. And I had never used an existing life as a kind of template.

Howard was a curious character, a worthy subject, and I felt kin to him in certain ways. Like me, he wrote both poetry and fiction, but I felt literally kin to him–he reminded me of certain unusual people and tendencies in my family tree.

The dusty places I returned to over and over again in the summers–little Collins and the tiny dot of Lexsy (near Swainsboro) in Georgia–had some strong parallels with Cross Plains. Back then, they were not the sort of locations that had the leisure or the desire for an artist in their midst. Both were places notable for heat, hard work, low Protestant churches, porch laughter and storytelling, and a focus on essential practical activities like making clothes or food preservation.

My Georgia summers, more than a little time spent in Texas, made me feel that I knew the highs and lows of the rural and small-town social scale, as well as what spoken and unspoken pressures could be brought to bear on a young person who wanted to be something very different than what the neighbors thought a child should be.

And any writer can figure out and understand another writer’s disappointments and sense of unfairness about how the world of publishing sometimes operates.

Did you always start out unraveling the story backward or how did that structure evolve?

Did you always start out unraveling the story backward or how did that structure evolve?

Maze of Blood was drafted during a stay at Yaddo back in 2007. Afterward, I sat on the book a long time before relinquishing it to a publisher who asked for a manuscript. About a year later, I asked for its return. I fiddled with it, feeling that something was not quite right.

Another request, another publisher, another year…

One morning, I woke up feeling that I knew exactly what to do to the book. I hadn’t thought consciously about the manuscript in months but must have dreamed a solution. Perhaps my sleeping mind was more intent on diving deeper than the waking one. I asked for the book’s return again.

The book was meant to say something strong and joyful about life and art, despite all the protagonist’s unmet longings… It was meant to insist on that strong, joyful gift–to shout out creation as an inextinguishable flame and a yes, yes, yes in the face of Conall’s despair, sense of failure (something all writers experience, as perfection can never be reached), anguish, exhaustion, and no.

How did you “know” the book was trying to say more? Do you see this in the outlining process or as you are writing?

Clearly I didn’t know what to do about Maze of Blood right away. I wrote the first version quickly and didn’t even know it wanted to be more when I finished the draft. And I can’t say that I reasoned out the idea that the book could be larger in its implications if I structured it differently. Certainly I came to feel that the book was meant to be more joyous–despite the crabbed culture, despite the blackness of suicide and dark of illness–than it was in the early incarnations

But I can’t say that I had worked out what to do; instead, my sleeping, dreaming self managed the business and determined the shape and new frame around the whole. The dream-me evidently knew how the book could say something that the life could not, would not say. That instinct arriving by dream should settle a problem may be slightly odd, but it is just as valid as any other mode.

You talk about the book like it’s a living entity, and I’ve heard that once or twice from other authors. How are you sure Maze of Blood wanted to be this? Is there ever another possibility that would have been equally as complete?

No book ever reaches the golden dream in the head, and there are surely many ways to lean toward that dream. I suppose deciding on a shape is not markedly different from working with a plant that can be trained to be espaliered, become an unusual topiary, or grow in a natural way. Many possibilities exist. The more you work with the plant, the fewer options remain. The more you work on a book, the more you close off the range of possibilities until you have chosen just one.

You’ve spoken in interviews before about a book telling you what it wants to be. Advice to first time novelists trying to figure out what their book wants to be?

Don’t try to figure it out. Daydream about your characters. Follow where story goes without attempting to force a direction. Pay attention to causal events. Then don’t be afraid to re-work and slash. Figure out where a story really begins (often not where the writer thinks it does.)

With the many years you worked on this manuscript, can you remember a specific “aha” moment?

Well, I don’t have those, not exactly–not an “aha” moment but sometimes a feeling of having worked everything out when I wake up in the morning, if it’s a big thing. I woke up with Thaliad burning in my head one morning, for example. And I had no idea of the story prior to that morning. It arrived at an extremely inconvenient time for me, but it was there all the same, tugging at me. I enjoy the sensation of new directions in a story leaping into the mind, but I can’t say that I am one who struggles to find the next step. Instead, I have much more of a sense of characters moving through time and space, and of running to keep up with them.

Again, I don’t think it matters how you go about writing, or whether you reason out a plot or move by instinct. What matters in the end is the book.

I suppose the main “aha” in my life is simply the ongoing desire to make poems and stories. The dream in my head is like the glimmering girl in “The Song of Wandering Aengus”–all crazy, bright transcendentals of beauty and goodness and truth. I can’t catch the ideal in this life; if I did, I would be done as a writer.

You’ve made me want to reread portions now. Conall glories in his imagination and storymaking despite the hardship this presents to him in real life. You also say you felt kinship, literal and figurative, with Howard. What hardships or difficulties does being a writer present for you either now or as you were growing up? (If that’s too personal, feel free to interpret however you’d like.)

I suppose there aren’t any genuine hardships for me in terms of the writing. Sometimes I might wish for more time, but writing leads me to a place of joy and freedom and pleasure. I like playing with words; I love the sense that language is streaming through me.

Publishing is another matter, and the situation is at least somewhat of a puzzle for all writers who do not have a push from a major publisher–that is, for writers with books that are not awarded lead or near-lead status in the Big 5. I’ve been with major New York publishers, university presses, and small presses, and they all present different sorts of benefits and hurdles. As a result of going in that direction, I’ve had books that look exactly as I wish; however, university and small presses tend to have a smaller staff and a thinner purse, and so they necessarily present difficulties to a writer in terms of promotion and bookstore reception.

Do you feel that storytelling is gift or craft, or a mixture of both?

It depends on what sort of writer you describe, I suppose. For some, it is one thing, some another. For me, putting words together still feels as magical as childhood’s reading and writing, and I would put storytelling firmly in the gifts category. The deep pleasure of words pouring through the mind is unlike most pleasures in my life, and it is not something that I would willingly do without. For me, making poems and stories has been a high, impractical, and life-altering calling. It has meant a devotion to praise for and joy in creation, without being untrue to human suffering and death. In his homage to Yeats, Auden said the poet must follow “To the bottom of the night” and “With your unconstraining voice / Still persuade us to rejoice.” I liked those lines when I was a girl, and I still like them. O’Connor said something similar when she wrote in a letter, “You have to cherish the world at the same time you struggle to endure it.”

For other writers, storytelling may be something more practical, and that doesn’t bother me a bit. It’s a big world, with room for other ways to be and other ways to think about making stories and poems out of words. Of course, revision with its tweakings and prunings and polishings appears much closer to writing as craft.

Are you ever stymied?

The one time I was stymied was the time a colleague–did we talk about this another time?–asked me what the world needed with another poem. That teasing, innocent question stopped the poems for a year. Imagine some children damming a stream with stones. The water cannot be held in, and seeps out to run away in a new direction. You could say that’s why I started writing stories. The water was my words, and they wanted to come out somehow, somewhere. So I suppose that I must bless my friend Tony for that tossed-off remark.

What does the process of noodling through the difficulties look like for you in tangible terms? For example, do you free write about a certain character issue or story structure issue?

No, I never free write like that. Maybe it would be better if I did! But I don’t, and don’t want to–I do all my exploration through the storytelling. Sometimes that means I am wasteful and throw away a good portion of a book. Poets like to cut, and so when a poet starts fooling around with novels, there will be sharp instruments and slashing of pages!

How do you tell if something wants to be a poem or a novel?

By the shape. Like a newborn, it is what it is upon arrival. Perhaps why it takes a certain shape is a mystery.

Do you have an average length of time you’ll give to a project?

My first agent, Thomas Epley, always told me never to tell how long I spend on a first draft. He thought I was too fast. But really, I am not so sure. It’s probably just that my hours are crammed together, that I am obsessive and will go without sleep in order to do what I have to do for my family but also progress on a book.

I have no idea how much time I spend, though everyone seems to think I am quick. But the other side of that thought is that I don’t sit in my chair to write every day, and that I spend great swaths of time writing only poetry (and so writing less often.) Writing for me is often a wasteful activity; I need time to be fallow and time to dream, and I want to be a poet as well as a fiction writer.

Have you ever abandoned a project? If so, why?

In a way, I have abandoned one book. Back when I was first working on a computer, I kept cutting a novel until it disappeared. I didn’t save all the versions, though I should have. My agent really liked that one, too, so it’ll have to be the mythical bird that burned itself up. Maybe it will come back again in some form, some day.

There’s much in the news about women writers being marginalized in traditional literary journals these days. Any thoughts on the plight of the female writer?

As far as journals go, I am certainly guilty of not having pursued requests and invitations as I should have, and not sending when invited to re-submit. It’s reported that men are far more forceful about such things. A lot of that has to do with having three children, being busy, and sometimes letting chances sift through the cracks. I’ve even been bad about not pursuing bites on larger things like movie options. I’ve been wayward since parting with my second agent.

I don’t fester over obstacles; we all have them, no matter what color or gender we are. While I may wish for my books to be better known than they are, I’m clear-eyed about the times, the general rage for entertainment and glitz, and the fact that it’s usually only lead books from big publishers that become well known. And I’m a little too occupied to try and alter the world.

Does the current challenge of commercial publishing ever cause regret for the time invested in a project?

Oh, I can be disappointed when I see that a publisher is not marketing a book, and that it will be nearly lost in a clamor of better-promoted books. But I can’t say that I’ve regretted any of my books in that way, or not for so long that I was tempted to stop writing or attempt to be more commercial. I just go commune with Dickinson, say, or Hawthorne and Melville, and afterward I feel pretty sure that a writer should simply make the most beautiful, strong work that she can make.

Thank you for spending time with us, Marly. It’s a pleasure to share your work with the WWWB group! Stay warm up there in Cooperstown and we wish you continued success and bountiful inspiration. Can’t wait to see what your imagination has in store for us next!

Favorite Books of 2015, Books and Culture Magazine

“This is one of the strangest books I have read in a long while, and also one of the best.” –Wilson’s Bookmarks, Christianity Today, 11/2015

“Maze of Blood is a haunting tale, but one so beautifully crafted by Youmans, unraveling in short chapters like prose poems constructed from spare dialogue, the dusty Texas landscape, a sudden flash of vibrant nature, and the sweep of a starlight sky… A haunting tale of dark obsessions and transcendent creative fire, rendered brilliantly in Youmans’ richly poetic prose.” –Midori Snyder, award-winning author

“Marly Youmans is the best-kept secret among contemporary American writers. She writes like an angel—an angel who has learned what it is to be human.” –John Wilson, editor, Books & Culture Magazine

“Marly Youmans is a novelist and poet out of sync with the times but in tune with the ages.”—-First Things

MAZE OF BLOOD is available –

Interviewed by –

Suzanne M. Brazil writes essays, interviews authors, reviews books, blogs about writing, and contributes to several other websites as well as the Chicago Daily Herald newspaper

Suzanne M. Brazil writes essays, interviews authors, reviews books, blogs about writing, and contributes to several other websites as well as the Chicago Daily Herald newspaper

She is a member of the Women’s Fiction Writers Association, Chicago Writers Association, National Book Critics Circle, and her local margarita-swilling book club.

Her work has appeared in national and regional publications. She is currently at work on her novel-in-perpetual-revision. Her other pursuits include ballroom dancing, the next lesson in her Older Beginner piano tutorial (who names these things, seriously?), dogsitting with her husband for their newlywed daughter’s rescue pups or sending care packages to her son in college. You can find her on her website, Facebook, and Twitter, where she loves interacting in all things bookish.

Category: Interviews