Putting Descartes In His Place

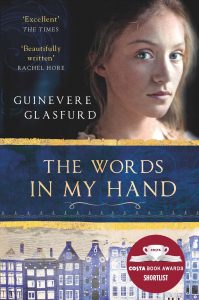

I want to tell you about the book that almost wasn’t written. The book I nearly gave up on before a word had been placed on the page. That book, my first book, has since been published in seven territories and was recently shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award 2017. All of this has been a source of near continual surprise.

I want to tell you about the book that almost wasn’t written. The book I nearly gave up on before a word had been placed on the page. That book, my first book, has since been published in seven territories and was recently shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award 2017. All of this has been a source of near continual surprise.

Let’s begin at the beginning, at the moment I realised I wanted to write about Descartes. I had this vague idea of three connected stories, each in some way relating to Descartes. Why? Because I had come across a reference to something he’d said or written or something – see, I told you it was vague – that ‘everything connects’. It seemed strikingly modern. But goodness, Descartes? Really? What did I think of when I imagined him? I shuddered a little, I think.

But where to begin when fictionalising the life of a known historical figure like Descartes? Someone once told me that a good starting point was this: ‘Don’t liable the dead.’ It’s sound advice. It did not mean that I could not cast a critical eye over the evidence. It did not mean I should fall at the feet of my characters. It did not mean I would let history off the hook. As I researched Descartes, as the pile of histories and scholarly articles on my desk grew higher, I began to see that clichés exist as much in history and in biography, as they do in fiction.

But I still did not know where to begin.

Then, as in all good stories, something happened. I came across a one-line reference to a Dutch maid, Helena Jans, and to the affair she had with Descartes. That was it. One line, before she was dismissed and the the focus returned to Descartes, his work, his essential ‘greatness’.

It’s startling, shockingly so, when a woman’s historical significance is dismissed in this way. There I was, laptop on knee, agog. At that moment, I knew I wanted to tell Helena’s story and to write the novel from her point of view. Of course, in telling her story, I would need to tell Descartes’ too. I would need to fictionalise him.

There were times, when I was writing my novel, when I was struck by an incapacitating fear. It was this: who was I to put words in Descartes’ mouth? More than once, this fear of speaking for Descartes, of fictionalising him, brought me to an abrupt halt. I backed away from the work, intimidated by it and by him.

I remembered my first meeting with my writing mentor, novelist, Katharine McMahon. We had talked about the difficulty of fictionalising known historical figures and why she had decided not to do so in her writing. She is by no means alone. Novelist, Helen Dunmore, has said that writers stray into ‘dangerous territory’ when they fictionalise real people.

I remembered my first meeting with my writing mentor, novelist, Katharine McMahon. We had talked about the difficulty of fictionalising known historical figures and why she had decided not to do so in her writing. She is by no means alone. Novelist, Helen Dunmore, has said that writers stray into ‘dangerous territory’ when they fictionalise real people.

But if I wanted to tell Helena’s story then I had no choice but to fictionalise Descartes. I could not tell her story without, in part, telling his. I faced the page with new resolve. But this determination to tell her story, in itself, was not enough to set me back on track.

As I thought about it, I realised that part of the problem seemed to be the pull that Descartes’ character had on the narrative, as though I’d set a magnet to one side of the page, and my words, like iron filings, were flying towards it, and him. This wasn’t the book I wanted to write. I had to elbow Descartes away. I rewrote a whole chunk of the book, not just holding him at arm’s length, but pretty much shutting the door to him. Then bolting it. And I told myself, again and again, so that I would not forget – this is Helena’s story, not his.

I used Descartes’ Correspondence as a way to find his voice and to escape the clichés that exist about him. I discovered a witty, acerbic, impatient, ambitious man; a man who did not tolerate fools. I found something gentle in his letters too: advice to friends, his grief. I fell a little in love with him in the end.

The evidence, although scant, is tantalising. I believe Helena mattered to Descartes. And I saw that Descartes, in the 1630s, was a considerably more uncertain man, not the towering figure of modern philosophy we now understand him to be. I realised that history could go only so far and that fiction was a means, (an equally valid one at that), of interrogating the past. Realising that was profoundly liberating.

I was able to put Descartes in his place and it set me free to write him. It set me free to write the book.

—

Guin Glasfurd’s short fiction has appeared in Mslexia, the Scotsman and in a collection from The National Galleries of Scotland. The Words In My Hand, her first novel, was written with the support of a grant from Arts Council England. She also works collaboratively with artists in the UK and South Africa and her work has been funded under the Artists’ International Development Fund, (Arts Council England and the British Council).

She manages the Words and Women Twitter feed, a voluntary organisation representing women writers in the East of England and can be found online at guinevereglasfurd.com and @guingb. She lives on the edge of the Fens, near Cambridge. Rights to the novel have sold in Germany (Ullstein Buchverlage), France (Livre de Poche), Netherlands (Luitingh-Sijthoff Amsterdam) and Spain (Siruela).

Find out more about her on her website https://guinevereglasfurd.com/

About The Words In My Hand

17th century Amsterdam.

A young maid desperate to learn.

An ambitious philosopher in search of the truth.

An unexpected affair – both of the mind and the body – that could ruin them both….

The Words in my Hand is the reimagined true story of Helena a 17th century Dutch maid, desperate to educate herself and use her mind, in an era where women were kept firmly in their place.

Helena works for an English bookseller who rents out a room to the mysterious ‘Monsieur’. On his arrival, ‘Monsieur’ turns out to be René Descartes. For all his learning, it is Helena he seeks out as she reveals the surprise in the everyday world that surrounds him. Descartes and Helena form an unlikely bond which turns from teaching into an affair.

Weaving together the story of Descartes’ quest for reason with Helena’s struggle for literacy, The Words in my Hand follows Helena’s journey across the Dutch Republic as she tries to keep their young daughter secret. Helena and Descartes worlds overlap yet remain sharply divided; the only way of being together, is living unseen. However, they soon face a terrible tragedy, and ultimately have to decide if their love is possible at all.

The Words in my Hand tells Helena’s story – a woman who yearned for knowledge, who wanted to write so much that she made her own ink from beetroot and used her body for paper.

‘Excellent’ The Times (Book of the Month)

‘A striking debut’ The Sunday Times

‘Wonderfully atmospheric’ Good Housekeeping

‘An absorbing and moving read’ Woman’s Weekly

BUY THE WORDS IN MY HAND HERE

Category: On Writing