A Lab Of One’s Own, Science And Suffrage In The First World War

Sharpley, Edith Margaret and Archer-Hind, Laura. ‘War Work, 1914-18.’ Manuscript at Newnham College, Cambridge. Photograph by Will Peck.

Serendipity is my favorite word and my guiding principle for research. Coined by society gossip Horace Walpole in the eighteenth century, it originated from an ancient Persian fairy tale about three princes from Serendib (now Sri Lanka), who travelled in new directions by taking advantage of whatever chance happened to throw at them. About five years ago, fortune rolled my personal dice and led me into an archive at Cambridge University, where the librarian proudly showed me a beautiful hand-made book with an embroidered linen cover.

Intrigued, I opened it to discover that almost a century ago, two women had recorded the activities during World War One of around six hundred female academics and students. Immediately, I sensed that this unique volume, so lovingly created and preserved, was offering me a glimpse into the vital contributions of scientific women who had been unjustly ignored.

Inscribed in exquisite red and black lettering were the names of chemists who developed explosives, biologists who researched into tropical diseases, mathematicians recruited for intelligence work, and doctors who operated at the Front. The very first page included a physicist who ran hospital X-ray departments, a mathematician who travelled to Serbia, and a scientist who survived a typhus epidemic abroad but died of pneumonia in London soon after returning home. Many had been rewarded with government or military honours, not only from Britain but also from Serbia, France, Russia, Belgium and Romania.

Gingerly leafing through the pages, I wondered why I recognised none of the names. Why did I know about self-sacrificing nurses such as Vera Brittain and Edith Cavell, but not the seven-women team who experimented with tear gas in experimental trenches dug in the gardens of Imperial College London? Why does Britain not commemorate the female doctors who ran hospitals under atrocious conditions in Salonika, or the London University professor of botany who headed the women’s army in France? Why were these extraordinary women absent from the numerous books detailing scientific, medical and technological advances spurred by the War?

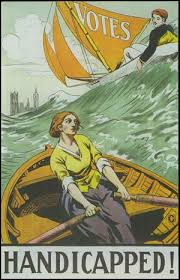

Duncan Grant, ‘Handicapped!’, 1909

Published as a poster by the Artists’ Suffrage League

Printed by Carl Hentschel

Archive of the Artists’ Suffrage League is at the Women’s Library, LSE Wikimedia Commons

Those questions continued to haunt me. A few days later, serendipity struck again. I was walking past the University Library – an imposing but uninspiring twentieth-century edifice – when I noticed a sculptor carving a memorial plaque. Apparently, the Library had been the wartime site of Cambridge’s military hospital – and then by another coincidence, I heard a radio interview with an elderly woman who had volunteered to help when she was a science undergraduate. Two weeks later, she was in charge of administering anaesthetics in the makeshift operating theatre, and then she trained as a doctor.

Abandoning the project I should have been doing, I resolved to create my own tribute to these scientific pioneers who had helped to win the War as well as the vote. There were already many marvellous books about the female ambulance drivers, munitions workers, and bus conductors who effectively ran Britain for four years while their menfolk were away.

I was determined to ferret out some more unusual and less familiar stories about highly-trained female scientists, engineers and doctors. Before long I had unearthed women monitoring industrial fatigue, carrying out ballistics calculations, inspecting factories, investigating how vitamins might be preserved in sun-dried vegetables, testing radio valves, improving high-quality glass, making artificial limbs, and compiling statistics on sugar production.

Although relatively few in number, they had a huge impact, yet their activities have been eclipsed. For four years, these trained and dedicated women proved not only that they could take over the work of men, but also that they could often do it better.

After the War, in science as in other fields, men returning from the Front reclaimed jobs that women had been competently carrying out in their absence.Yet although the old stereotypes and prejudices re-emerged, there were more possibilities for scientific women than before because the government was pouring money into science, industry and education. They were still not getting their fair share, but at least the cake was larger. Women had proved themselves capable of carrying out work traditionally reserved for men, and – try as reactionaries might – that unprecedented sense of achievement and power and possibility could not be obliterated.

British society had been indelibly altered, so that although the future seemed unsettled, there was no going back to the fixed and oppressive certainties of the past.

Marie Stopes in her laboratory, 1904 Wikimedia Commons

What happened a century ago is important for understanding the present. My mother was born in 1918, the year British women over 30 gained the right to vote, and she inevitably passed on to me the hopes as well as the fears of her generation. Like many of my own contemporaries, I have tried to continue the initiatives of my predecessors and improve the position of women in science.

I wrote A Lab of One’s Own as a paean to the pioneering scientists and doctors whose lives have been obscured, but who collectively made my own professional career possible. Traditional prejudices still resonate through society, and glass ceilings still restrict women’s rise to the top. The pace of change remains frustratingly slow, but I like to hope that the scientists and doctors so carefully listed in that linen-covered book would have been gratified by the progress that has been made.

Exploring the past is important for understanding how we have reached the present – and for me, the whole point of doing that is to improve the future.

—

Patricia Fara is currently President of the British Society for the History of Science and a Fellow of Clare College, University of Cambridge. She has written numerous books on the history of science, including her prize-winning Science: A Four Thousand Year History, which has been translated into nine languages. As well as giving many public lectures every year, she appears regularly on TV and radio programs such as the BBC’s In our Time.

Patricia Fara is currently President of the British Society for the History of Science and a Fellow of Clare College, University of Cambridge. She has written numerous books on the history of science, including her prize-winning Science: A Four Thousand Year History, which has been translated into nine languages. As well as giving many public lectures every year, she appears regularly on TV and radio programs such as the BBC’s In our Time.

About A LAB OF ONE’S OWN

Patricia Fara unearths the forgotten suffragists of World War I who bravely changed women’s roles in the war and paved the way for today’s female scientists.

Patricia Fara unearths the forgotten suffragists of World War I who bravely changed women’s roles in the war and paved the way for today’s female scientists.

Many extraordinary female scientists, doctors, and engineers tasted independence and responsibility for the first time during the First World War. How did this happen? Patricia Fara reveals how suffragists including Virginia Woolf’s sister, Ray Strachey, had already aligned themselves with scientific and technological progress, and that during the dark years of war they mobilized women to enter conventionally male domains such as science and medicine. Fara tells the stories of women including mental health pioneer Isabel Emslie, chemist Martha Whiteley, a co-inventor of tear gas, and botanist Helen Gwynne Vaughan. Women were carrying out vital research in many aspects of science, but could it last?

Though suffragist Millicent Fawcett declared triumphantly that “the war revolutionized the industrial position of women. It found them serfs, and left them free,” the truth was very different. Although women had helped the country to victory and won the vote for those over thirty, they had lost the battle for equality. Men returning from the Front reclaimed their jobs, and conventional hierarchies were re-established.

Fara examines how the bravery of these pioneers, temporarily allowed into a closed world before the door slammed shut again, paved the way for today’s women scientists.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing