On the “Critical vs. Creative” Divide

As an English instructor, one of the most common claims I hear from students is that they are either “critical” or “creative” writers. Academic writing is dry and logical and difficult, they insist; by contrast, fiction writing is freeing, enabling, liberating. Sometimes they put the two into a relationship: creative writers make the art, and critics analyze it. Or, as one of my undergraduate creative writing instructors put it, “it’s like we’re the ones who make the furniture, and they’re the ones who sit in it!”

As an English instructor, one of the most common claims I hear from students is that they are either “critical” or “creative” writers. Academic writing is dry and logical and difficult, they insist; by contrast, fiction writing is freeing, enabling, liberating. Sometimes they put the two into a relationship: creative writers make the art, and critics analyze it. Or, as one of my undergraduate creative writing instructors put it, “it’s like we’re the ones who make the furniture, and they’re the ones who sit in it!”

This view is understandable. We live in an age of intense specialization, after all, where creative writing and essay writing and technical writing and journalism are all taught as different forms. Often, academic essays remind students of the stultifying timed writing they performed in middle and high school, where they learned to cough up short essays with little reflection or personal investment. And the marketing categories we encounter in bookstores and through online retailers—categories like “Literary Fiction,” “Literary Criticism,” “Genre Fiction,” and so on—only confirm our belief that writing falls into neat categories.

Still, I believe that this view – that there is a strong difference between “critical” and “creative” writing – is deeply flawed. Even worse, people who hold this view miss out on crucial opportunities to deepen and improve their creative writing.

For one, this view ignores the vast scores of writers who write both critically and creatively: Alice Walker, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Oscar Wilde, Toni Morrison, and Viet Thanh Nguyen, to name just a few.

Even more worryingly, this view implies that there is a stark difference between the analytical and the creative mindset: that one cannot be an analyst and an imaginative thinker simultaneously.

It is true that the processes of brainstorming, outlining, and drafting critical and creative work can feel radically different. One comes entirely from research and deep reflection and often analyzes some other art form—a book, a film, a performance—the other, perhaps, comes from a personal experience heightened and distorted into fiction, or from a plot or character that stems entirely from the imagination, or from a single image or word or encounter.

But, these general differences aside, academic writing has the potential to enrich creative writing more than people think. Academic writing is really about ideas: ideas that range from gender and sexuality and race and ethnicity and history and war to family life and kinship and travel and artificial intelligence and space exploration and more.

It is about setting aside one’s preconceived notions about a subject in order to explore it more fluidly, more openly. It is about being your best thinking self, so that you can communicate surprising and unexpected angles to others, to challenge or question what readers already assume or know. And what is more important, more crucial for a writer, than the ability to be open to new possibilities, to encounter new ideas?

Some readers dislike academic writing because of its perceived difficulty and inaccessibility to non-academics. I will concede that many academic essays are saturated with difficult language–a product, in part, of the intense disciplinary specialization I mentioned above. Yet not all academic writing fits this description. My students often express pleasure and surprise at the momentum and accessibility of classic critical works like Chinua Achebe’s “An Image of Africa” or Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s A Madwoman in the Attic because these exciting, well-written pieces challenge their preconceived notions of what academic prose should sound like.

Other readers complain that critical writing has too much jargon. People who make this complaint often forget that all professional, vocational, and creative communities have their own specialized vocabularies. The academic essay shares this in common with the legal brief and the mechanic’s report. Scientists use specialized vocabulary to describe their findings, psychologists use specialized vocabulary to treat their patients, and sports newscasters use sports-specific jargon to narrate plays throughout a game. Why should critics who write essays be any different?

Finally, we can’t ignore the social and political contexts of our attitudes towards writing. Exalting the creative process and putting it on a pedestal can feed into a Romantic cult of genius—one that seeks to legitimize or dismiss abusive and unethical behavior. This myth of the solitary genius can also fuel exclusionary notions of the Author-with-a-capital-A whose work is wholly individual, not collaborative or profoundly intertwined with the writing and thinking of others. (For a challenge to this myth, check out the open-access digital resource developed by Amardeep Singh, James McAdams, and Sarita Mizin at Lehigh University, “The Kiplings and India.”)

Working through a piece of academic writing can teach you patience and concentration. And patience and concentration are essential parts of any writer’s life. It can teach you humility, the importance of holding yourself open to other perspectives, and the importance of not settling for easy or simple or preconceived answers. Like any encounter with words, it can heighten your receptiveness and sensitivity to the nuances of language and ideas. And the process of drafting and re-drafting an essay, of distilling your idea into its clearest and most exciting form, is good practice for the kind of perseverance and light detachment you need to read and revise your own fiction.

So, the next time you are tempted to dismiss critical writing as difficult or irrelevant, I urge you to reconsider. You might check out writers like Maggie Nelson and bell hooks, writers whose prose seems to slide effortlessly between critical and creative modes, or research a topic you’d like to understand better, or even think about the kind of specialized language you encounter every day. You just might be surprised at what you can write when you are alive to all of the genres and modes of expression, to a full range of writerly forms.

-Barbara Barrow

Follow her on Twitter https://twitter.com/dustyoldbagz

Find out more about her on her Website https://www.barbarabarrow.com/

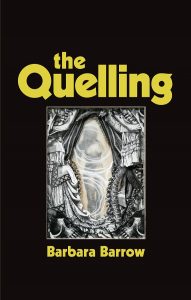

Addie and Dorian have always been together: the two sisters have spent most of their lives in a locked ward after being diagnosed with a rare psychiatric condition and accused of murder as children. Now on the cusp of adulthood, Addie plans to start a new family to replace the one she lost, while Dorian struggles with her own violent tendencies to help raise her sister’s child. But Dr. Lark, the supervisor of their ward, sees these patients as the key to his revolutionary Cure. As his “treatments” become increasingly bizarre, Addie and Dorian are increasingly unsafe, and a ward nurse may be their only lifeline.

Addie and Dorian have always been together: the two sisters have spent most of their lives in a locked ward after being diagnosed with a rare psychiatric condition and accused of murder as children. Now on the cusp of adulthood, Addie plans to start a new family to replace the one she lost, while Dorian struggles with her own violent tendencies to help raise her sister’s child. But Dr. Lark, the supervisor of their ward, sees these patients as the key to his revolutionary Cure. As his “treatments” become increasingly bizarre, Addie and Dorian are increasingly unsafe, and a ward nurse may be their only lifeline.

>“The Quelling—ferocious, tender, astonishing—lays bare our animalistic drives toward violence and love, and our human impulse to cure and to control. Barbara Barrow‘s story of the sharp sisters Addie and Dorian, and the strange and transgressive Dr. Lark, brims with terrifying insights and the eerie intimacy of dreams.”

Pre-order now:

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips