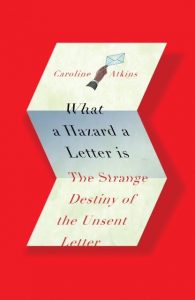

What A Hazard A Letter Is: The Strange Destiny Of The Unsent Letter

I’ve always been fascinated by letters. Listening to Sylvia Plath’s being read on Radio 4 reminds me just how powerful they are, how swiftly they take us back into former lives – our own and other people’s. And for biographers, letters are like buried treasure. The American author and journalist Janet Malcolm describes them as ‘fossils of feeling’, because when we dig them up we find the past, just as it was, unfiltered by time or interpretation.

I’ve always been fascinated by letters. Listening to Sylvia Plath’s being read on Radio 4 reminds me just how powerful they are, how swiftly they take us back into former lives – our own and other people’s. And for biographers, letters are like buried treasure. The American author and journalist Janet Malcolm describes them as ‘fossils of feeling’, because when we dig them up we find the past, just as it was, unfiltered by time or interpretation.

She trawled through fascinating correspondence in her brilliant book The Silent Woman, about Sylvia Plath’s relationship with Ted Hughes. Read Plath’s letters from Cambridge, recounting her early impressions of Hughes – ‘half French half Irish, with a voice like the thunder of God…Ted is incredible, mother…wears always the same black sweater and corduroy jacket with pockets full of poems, fresh trout and horoscopes’ – and you get a more immediate sense of the man, and of her feelings for him, than any observer could have described.

Everyone should read The Silent Woman – it’s unputdownable. But there’s an incident towards the end of it that lodged itself in my mind and wouldn’t go away. In the process of researching Plath’s life, Janet Malcolm writes a letter to another biographer, which she then decides on reflection not to send. Even more interesting, aware that the letter, just by being written, now has its own place in the world, she files it away rather than tearing it up. ‘The genre of the unsent letter might reward study,’ she says. ‘We have all contributed to it.’

Which is what gave me the idea for What a Hazard a Letter is: The Strange Destiny of the Unsent Letter. Especially when I realised, going back through old diaries, that I had contributed several of my own (one of them, embarrassingly, in turquoise ink – which perhaps marked it out as ‘not to be sent’).

The problem, of course, was how to track down examples when I didn’t know that they existed in the first place. If a letter hasn’t been sent, how do you know where to find it? Some sprang to mind straight away – Beethoven’s famous letter to his Immortal Beloved; Emily Dickinson’s Master Letters, to an unidentified 19th-century crush.

Others involved a bit of lateral thinking and the help of my publisher, Graham Coster of Safe Haven Books: checking out prolific letter-writers who might have left one or two unsent (we hit the jackpot with Virginia Woolf’s Middlebrow letter to the New Statesman), scanning the introductions and indexes of collected correspondence and diaries for possible leads to follow. The London Library was an invaluable resource for this, stocked with every possible author and enveloping me in leather-bound memories of past lives.

People soon caught on, and almost every time I mentioned what I was working on, someone would say, ‘Oh, my family has one of those.’ Including the friend who sent me a photograph of the letter that his great-uncle, an officer with the Seaforth Highlanders, wrote home from the Trenches to his commanding officer in April 1917. It was found on him when he was killed a couple of days later, still unsent, with its poignant PS: ‘Do you see any prospect of a fairly early termination of hostilities?’

And when I started hunting through history and literature, I found them everywhere. US presidents from Lincoln to Truman frequently used unsent letters as a way of letting off steam – having a private rant before calming down and filing the document away (whereas now, of course, we have a president who Tweets to the world at all hours, apparently without a second thought). In more recent political history, letters that weren’t sent include the one Boris Johnson wrote to Andrea Leadsom after the EU Referendum, offering her a top job in his cabinet if he won the leadership election that following David Cameron’s resignation.

Because the letter remained unsent, she withdrew her support and decided to stand for the leadership herself, the Johnson campaign imploded and Theresa May was handed the premiership on a plate.

The book’s title comes from a letter – later turned into a poem – of Emily Dickinson’s. She was thinking of the way letters can (or could, in the days before social media) deliver earth-shattering news, but I wanted to explore the additional hazards of a letter being misdirected or otherwise lost in transmission. Which brings us to all those letters from fiction, that form key plot devices or leave powerful feelings unsaid.

The one Tess pushes under the door to Angel Clare in Tess of the d’Urbervilles, not realising that it’s also gone under the carpet on the other side. The one that Robbie in Atonement leaves on his writing desk, only realising as he hands over the envelope that it contains the earlier, frankly erotic first draft that he didn’t mean to send. The one Dexter writes to Emma in David Nicholls’ One Day, asking her to join him in India – but then leaves unsent in a backpackers’ bar so that it’s another 11 years before they finally get together.

I loved having such a good reason to revisit old favourites of mine. Dorothy L Sayers’ Gaudy Night, in which Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane agonise over how much to admit their feelings for each other. And Anthony Buckeridge’s school stories: the postcards that Jennings and Darbishire attempt to write home to their parents are sheer joy – the kind of ever-reliable pleasure that you dig out to brighten your glummest day.

Books that lead you into other books are extra satisfying. I was reminded of that recently when I read Susan Hill’s Jacob’s Room is Full of Books, and I hope readers will enjoy discovering some of the wonderful novels I come across while researching What a Hazard. Paul Wilson’s Mouse and the Cossacks, where an 11-year-old girl who hasn’t spoken for years regains her voice by reading a cache of undelivered letters found in her new house; Olaf Olafsson’s Walking Into the Night, in which the narrator writes desperate, guilt-ridden letters that he will never send, to the wife he deserted 20 years earlier; and Claire Fuller’s Swimming Lessons, which is scattered with letters hidden inside books, to be chanced upon in random order…

Exploring all these letters, the circumstances that led to them being unsent or mis-sent, and the consequences, was endlessly fascinating. I’ll be on the lookout for more examples from now on – and I’ll probably not send a few of more my own, too.

—

Caroline’s book What A Hazard A Letter Is: The Strange Destiny of the Unsent Letter is published by Safe Haven, £14.99. ‘A charming book, witty, original and wise’ – Christopher Hart, Sunday Times

• Caroline Atkins is a writer, editor and painter. She works as a freelance editor for the Mail on Sunday’s YOU magazine and contributes regularly to Country Living and Modern Rustic. She has written several books on interior design and shown paintings in London galleries including the Mall Galleries and the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. More information about her work at carolineatkins.wordpress.com Twitter: @CaroAtkinsBooks

What a Hazard a Letter Is: The Strange Destiny of the Unsent Letter

Why would anyone write a letter and then not send it? What a Hazard a Letter is, wrote the poet Emily Dickinson, thinking of the Hearts it has scuttled and sunk. Once sent, a letter cannot be taken back: it is like a depth charge dropped into the future, into other people s lives.

Why would anyone write a letter and then not send it? What a Hazard a Letter is, wrote the poet Emily Dickinson, thinking of the Hearts it has scuttled and sunk. Once sent, a letter cannot be taken back: it is like a depth charge dropped into the future, into other people s lives.

The moment they are written, letters become, as Janet Malcolm puts it, fossils of feeling: they fix and freeze the sentiments we had at the time, though our lives may quickly move on and we may all too soon have second thoughts. But what if, once written, a letter is not sent or never arrives?

What a Hazard a Letter is is the first book to look at the strange phenomenon of the unsent letter. It collects together some of the most remarkable examples, from fiction and from real life, and explores the fascinating reasons why they came to be unsent, and the consequences sometimes farcical, sometimes agonisingly poignant, and sometimes actually changing the course of history.

Here, then, are authors from Ian McEwan to Iris Murdoch, Abraham Lincoln to Ernest Hemingway, and Virginia Woolf to Van Gogh: magnificent tirades written in the red mist of rage, delicious to read but all the better for not being mailed; letters whose non-arrival sets a novel s plot careering down a new track; and tender words of love that never quite got said all, in their way, a little more eloquent for being unsent.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing