Looking Back to Look Forward: Or, Why We Read Historical Fiction

By Carrie Callaghan

By Carrie Callaghan

This is a true story.

In the winter of 1938, before Hitler invaded anything, Milly Bennett sat in a room in New Jersey and looked out the window. Seven or eight children dressed warmly laughed and pulled their sleds in the snow. She typed, “I have looked into the future and it is catastrophic unless — The hate and murder and destruction that is growing and spreading and over-running Europe is stopped, somehow.”

Milly had just returned from Spain, where she worked as a propagandist for the besieged, leftist Spanish government and an independent war correspondent reporting on the civil war. It must have been in her freelance capacity that she went to the Valencia morgue one night in 1937 after an air raid. Candle in hand, she counted the bodies, while nearby family members screamed upon finding their dead. “Sixty three, sixty four, sixty five,” she counted.

“This girl is eight,” Milly guessed, looking at one small body. “with her face turned sideways as if away from the light.”

“I must go on counting, I must get a telephone line quickly to London, to my news agency office,” she wrote later. “I must tell the world about this useless, needless slaughter of little children and old folks.”

Milly lived at an uncertain moment, when a nation tired of war and economic malaise prayed that its statesmen could negotiate well enough to keep a second war at bay. They couldn’t, of course, and she suspected as much, having seen the slaughter waged by Fascist forces in Spain. But no one knew, not like how we now know, with the benefit of hindsight.

There is a magic in unknowing our history and seeing the past through the eyes of those who lived it. We can do that by reading their words: their diaries, letters, and books. But so often, that feels like only half a bridge, like knowledge floating away from understanding. Because contemporary readers are so firmly anchored in our moment, and wondering about what our future holds for us, we yearn for stories that explain the past in a way that connects those past lives to our current ones.

Historical fiction can do that. Writers today cannot leave behind our worries about politics or climate change or prejudice, and the stories we tell are influenced by those concerns. But those stories are also driven by the past, by the truth of wanting to tell what happened to people like Milly Bennett and the poor eight-year-old girl whose body she found in a Valencia morgue.

History lets us learn the billions of other ways humans have lived their lives, and fiction invites us into those lives through the beguiling magic of story. No life is ever one single story, and nearly every earnest story has truth to it. The more stories we learn, the more truth we absorb.

Milly could do little to alter the catastrophic future she saw on the horizon, but perhaps her writing still saved some lives: maybe she drove people to donate to Spain, to provide food and medical care for victims. She told her truth, both in her newspaper articles and in her letters and personal papers. I wrote what I hope is part of her truth too: the novel about her life that she couldn’t finish in her own time.

In a time when we grapple with the very existence of truth, amid the cries of fake news and lying politicians, perhaps there is something to be gained by walking back along the bridge of history to look at the life of a woman who wrote optimistic stories about a doomed society. Milly Bennett couldn’t always discern what the truth was either, but she spent her life trying to find it and share her stories. She and all the ghosts of the past hold out their hands to us.

—

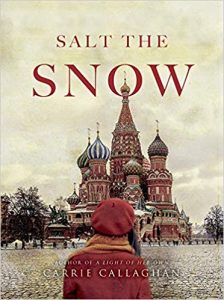

Carrie Callaghan is the author of “Salt the Snow,” (Amberjack, Feb. 4, 2020), her second novel. She lives in Maryland with her family, and she drinks altogether too much tea.

Find out more about her on her website http://www.carriecallaghan.com/

Follow her on Twitter @CarrieCallaghan

SALT THE SNOW

American journalist Milly Bennett has covered murders in San Francisco, fires in Hawaii, and a civil war in China, but 1930s Moscow presents her greatest challenge yet.

American journalist Milly Bennett has covered murders in San Francisco, fires in Hawaii, and a civil war in China, but 1930s Moscow presents her greatest challenge yet.

When her young Russian husband is suddenly arrested by the secret police, Milly tries to get him released. But his arrest reveals both painful secrets about her marriage and hard truths about the Soviet state she has been working to serve.

Disillusioned and pulled toward the front lines of a captivating new conflict, Milly must find a way to do the right thing for her husband, her conscience, and her heart. Salt the Snow is a vivid and impeccably researched tale of a woman ahead of her time, searching for her true calling in life and love.

Category: On Writing