The Kitchen is My Refuge, By Meera Ekkanath Klein

Self-reliance and simplifying one’s life has never been more attractive. With Shelter-in-Place orders, there seems to be a need to find that magical inner combo of Marie Kondo and wise grandmother. Old-time wisdom, especially in the kitchen, is in high demand right now.

Self-reliance and simplifying one’s life has never been more attractive. With Shelter-in-Place orders, there seems to be a need to find that magical inner combo of Marie Kondo and wise grandmother. Old-time wisdom, especially in the kitchen, is in high demand right now.

I’m a product of my family and so when I need inspiration or a dose of commonsense, I turn to my ancestors for motivation and meaning. From my mother to my great-granny I have a treasure trove of advice to help me cope with pretty much any situation.

The kitchen is where my mother’s influence shines. Just like my mother, I mutter a prayer to Agni (Lord of Fire and Household) before I add rice or pasta to boiling water. My mother never tasted her cooking; she relied on her nose to tell her when the spices were roasted.

In this, she was a lot like my late mother-in-law Betty who never used the kitchen timer when baking her famous apple pies. Somehow her nose knew when the pie was ready. Her apple pie was sprinkled liberally with cinnamon and love.

When there was a flour shortage, I remembered my mother’s trick of adding cooked potato (or other vegetables such as cauliflower or beets) to roti dough to make more from less. Chickpea flour makes a cheap and nutritious sauce for vegetables, grains and stews and replaces butter, milk and cheese.

So in an age of uncertainty and unease, the kitchen has become a refuge for me (like many others). In our kitchen I dig deep into my memories for recipes and tips on cooking without waste.

I admit I learned a lot from watching women role models like my mother and my mother-in-law work their magic. In my childhood kitchen there were no cookbooks or recipes. Along with the cooking lessons there were stories of bygone ancestors my mother liked to share as she made spice blends or toasted cashew bits in warm ghee.

I admit I learned a lot from watching women role models like my mother and my mother-in-law work their magic. In my childhood kitchen there were no cookbooks or recipes. Along with the cooking lessons there were stories of bygone ancestors my mother liked to share as she made spice blends or toasted cashew bits in warm ghee.

Stories about granny Pearl’s kindness and compassion and her skill as a pastry cook. Her nimble fingers were able to twirl the chickpea dough into a huge circle, in some cases 101 times around, without a single breakage.

The pastry circle was made of chickpea flour flavored with cumin seeds, red chili pepper powder and sea salt. The completed pastry or muruku was air dried and then deep fried for a melt-in-your mouth treat.

Another granny Ammalu was a story-teller, a lover of hot tea and spicy lentil snacks. She used to take us to the local tea stall for a session of gossip and hot tea. The tea stall owner served us tiny glass tumblers of sweet tea, topped with milky foam. He created the foam by pouring the hot beverage from one container to another. I was always fascinated by the long stream of never-ending liquid undulating like a pale-orange snake. I always waited for him to spill the tea but the long stream stayed unbroken until he poured it into the glass tumblers. The tea was served with spicy lentils, crunchy with bits of onion, green chili and ginger.

Mother told me about our great-granny who was fearless and a staunch defender of the weak. She saved many a dog from being harmed, bullocks from being beaten and little children from being punished unfairly. When a villager died, Great-Granny was called to sit with the dead. She kept a lonely vigil with the corpse, with just an oil lamp for company. The dead are not scary, she used to say, it is living you have to fear.

These life lessons from my mother’s frugal kitchen are more than just a way to cook with thrift; it is a connection to my past and to my ancestors. With my mother, Granny Pearl, Granny Ammalu and Great-Granny to keep me company, my kitchen is never lonely.

—

Meera Ekkanath Klein is the author of two novels and lives in California. Check out her website: http://meeraklein.com

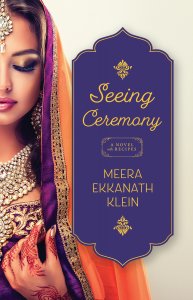

SEEING CEREMONY

This feel-good sequel to the award-winning My Mother’s Kitchen is all about family, good food, love and finding the way back home. Since the death of her husband three years ago, Meena’s mother has wanted to see her oldest daughter married and so she organizes Meena’s “seeing ceremony,” a ritual associated with arranged marriages. However, eighteen-year-old Meena is not ready to be married and wants to leave her hilltop home in Mahagiri, south India, and attend college in California.

This feel-good sequel to the award-winning My Mother’s Kitchen is all about family, good food, love and finding the way back home. Since the death of her husband three years ago, Meena’s mother has wanted to see her oldest daughter married and so she organizes Meena’s “seeing ceremony,” a ritual associated with arranged marriages. However, eighteen-year-old Meena is not ready to be married and wants to leave her hilltop home in Mahagiri, south India, and attend college in California.

The ceremony is a disaster. Her four years in America soon comes to an end and Meena is eager to return home and share her newly-acquired knowledge of agriculture and tea production with her family. On her journey back to India, Meena meets handsome businessman Raj Kumar with whom she has an instant connection. They end up talking for hours in the airport lounge. When they part at the departure gate, Meena doesn’t think she’ll ever see Raj again. Back in Mahagiri, her mother faces a threat to her home and livelihood. Meena could avert this disaster by agreeing to an arranged marriage. Will Meena have to go through yet another “seeing ceremony?”

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: On Writing