How Do You Know? On Dubious Faith And Intermittent Certainty In Writing

We eat with our eyes, the saying goes, but our eyes are unreliable gauges of appetite and we often order more than we want. We believe in science, we say, but I read somewhere recently that it is impossible to ‘believe’ in science, which is itself fact and thus requires no articles of faith. Actually. (As a sometime humanist, I felt a bit slapped after reading that, to be honest.) For writers, there is no science, there is only faith in the words and the endless question of ‘how do you know?’

We eat with our eyes, the saying goes, but our eyes are unreliable gauges of appetite and we often order more than we want. We believe in science, we say, but I read somewhere recently that it is impossible to ‘believe’ in science, which is itself fact and thus requires no articles of faith. Actually. (As a sometime humanist, I felt a bit slapped after reading that, to be honest.) For writers, there is no science, there is only faith in the words and the endless question of ‘how do you know?’

How do you know it is the right idea, the right character, the right voice, the right decision, the right ending, the right edit? If right is the endless unknown, then wrong is its polar opposite – the dogs in the street can spot wrong from a mile away.

In 2013, Tim Minchin gave a graduation speech at the University of Western Australia (available online and well worth your 12 minutes). Full of warmth and wisdom, what stood out for me is his advice to ‘be hard on your opinions.’ I think of that every time I sit down to edit a story. Questioning and interrogation have no place in first drafts but by the time you’re coming back for round two, you’re working to figure out what exactly your story is and such scrutiny is not only useful, it is essential.

Being hard on your beliefs is equally important (although significantly tougher) when someone else gives you their critique. Let it sit. Let it settle. See if it sticks. You might find that it goes right to the little voice that already had doubts about that very thing they’ve singled out. When you look again, with a less bruised spirit, you might even find their take is now holding hands with the bit of you that suspected that plot point was convenient, that character under-used, that setting thin.

Underneath the dread of the work it will take, you may even find yourself energised at the idea of the changes that will need to be made. I once cut one-third of a novel on a flight between Cork and London. I sat down to do a routine edit and by the time we landed, I had decided to get rid of one character’s point of view. It would be months of work but I knew I was right and that keeping the character would tilt the story in a direction I didn’t want. If you’re resisting cuts and changes, whether your own or those of a trusted early reader, be sure that it because you have thoroughly interrogated your reasons for keeping whatever it is and you are prepared to stand over it. Don’t fight feedback just because you don’t want to do the work.

Which raises the question: how do you know something is right? This is a tricky one and answers are likely to feature some variation on what we are told when we ask about love: ‘you just know’. True, maybe, but also enormously unhelpful when you’re at your desk or in your car or wherever else you go to hang out inside your mind. Well, when it comes to knowing whether or not something is right for a story, here’s how I know: I feel a kind of quickening, as if I’ve been holding my breath, and at the same time a kind of settling.

A certainty that is the very opposite of free-floating anxiety. If anything, it feels like recognition, as if the right thing – the idea or phrase or character or theme – was just waiting for me to happen upon it. I studied Applied Psychology many moons ago, back when cognitive psychology – the nature of the mind and thought and memory – was the big thing.

At the time, short-term memory was believed to be able to hold a certain number of chunks of information (seven plus or minus two, which I roped my friends into lab experiments to prove) and those chunks had to be transferred into the separate storage system of long-term memory if they were to be retained and retrieved a week later, or a month later, or beyond that again.

One theory of déjà vu that appeals to me is that it is the brain catching itself in the act of transcribing information from short-term into long-term memory, so the long-term memory seizes on it as something from the past even while it is still happening. Catching a glimpse of our own brain mechanics at work, as it were.

While theories of memory have moved on, whenever I think about how I know whether or not something is right for a story, this mechanistic theory of déjà vu is what I think of: an idea that has been floating in the background as the product of all the work and thought and love and life that goes into creating a story. The feeling of quickening and recognition is simply me catching my unconscious mind in the act of pushing something into a space where I can find it.

As writers, we have to decide on the balance of reliability and uncertainty in our paper worlds. Everyone can – and will – tell you what wrong looks like but right is something only the writer themselves can know, whether as an emotional resonance or a reverberation or a gleeful leap-out-of-the-bath certainty. The least we owe our readers is the certainty that our decisions have been made in good faith – and then roundly interrogated.

Social media

Twitter: @GraMurphy

Instagram: @gramurphywriter

—

Gráinne is an Irish writer who grew up in Cork and has now returned there to write, read and drink coffee. She writes long and short fiction, and occasionally poetry, when big emotions need to be safely contained. A winner of the Irish Writers’ Centre Novel Fair 2019, her novels have been shortlisted for the Caledonia Novel Award 2019 and Blue Pencil Agency First Novel Award 2019 and longlisted for the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize 2018 and Mslexia Novel Award 2017. Her short stories have appeared in the Fish Anthology 2020, RiPPLE Anthology 2017 and Nivalis 2015. Gráinne is chiefly interested in family and identity, in those bittersweet moments where we have to stare life down and choose who we want to be.

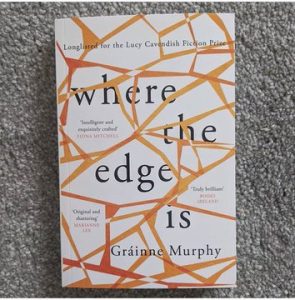

Gráinne’s debut novel Where the Edge Is was published by Legend Press in September 2020. The Ghostlights is due in 2021, also from Legend Press.

WHERE THE EDGE IS

‘A suspenseful, beautifully crafted debut, which is written with feeling and tenderness’ Irish Examiner

‘A suspenseful, beautifully crafted debut, which is written with feeling and tenderness’ Irish Examiner

‘A truly brilliant debut’ Emily Mazzara, Books Ireland

‘With sentences that you will want to cut out and keep, this is an intelligent, exquisitely crafted debut’ Fiona Mitchell

‘Original and shattering’ Marianne Lee

As a sleepy town in rural Ireland starts to wake, a road subsides, trapping an early-morning bus and five passengers inside. Rescue teams struggle and as two are eventually saved, the bus falls deeper into the hole.

Under the watchful eyes of the media, the lives of three people are teetering on the edge. And for those on the outside, from Nina, the reporter covering the story, to rescue liaison, Tim, and Richie, the driver pulled from the wreckage, each are made to look at themselves under the glare of the spotlight.

When their world crumbles beneath their feet, they are forced to choose between what they cling to and what they must let go of.

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips