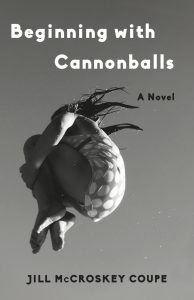

Interracial Friendship in Fiction By Jill McCroskey Coupe

In my novel Beginning with Cannonballs, two infant girls, Hanna and Gail, share a crib in Gail’s parents’ house, where Hanna’s mother is the live-in maid. This is in the 1940s in segregated Knoxville, Tennessee, where I grew up. Despite having to attend different schools, the girls become close childhood friends. After that, it’s not so easy.

In my novel Beginning with Cannonballs, two infant girls, Hanna and Gail, share a crib in Gail’s parents’ house, where Hanna’s mother is the live-in maid. This is in the 1940s in segregated Knoxville, Tennessee, where I grew up. Despite having to attend different schools, the girls become close childhood friends. After that, it’s not so easy.

My MFA thesis, a novella, written decades ago, was also about an interracial friendship. A group of my classmates, all of them white, insisted that, as a white person, I could not, should not write about black characters.

Although I disagreed with them, I put my thesis away and haven’t looked at it since. But I never gave up on the idea, and, about eight years ago, I decided to try again. Beginning with Cannonballs tells a completely different story, with entirely new characters. Only the scene in an empty swimming pool bears any resemblance to my first effort.

Remembering the criticism I’d received, I was curious to know how others have handled this. A fairly thorough search revealed that most books about interracial friendship have been written by white women, with children and young adults as the intended audience.

Luckily, I was able to find four beautifully-written novels for adults. In one way or another, each harkens back to the Jim Crow era. Without giving away the endings, I’ve provided brief descriptions of these novels below.

In Stranger Here Below (Unbridled Books, 2010), by Joyce Hinnefeld, two young women become friends when they room together in the 1960s at Berea College in Kentucky. Maze (short for Amazing Grace) is an outgoing Appalachian gal, while Mary Elizabeth is the reserved, musically talented daughter of a black preacher. When Mary Elizabeth gives up on her music and leaves school, the friendship falters. Years later, however, the women attempt to resurrect it.

Calling Me Home (St. Martin’s, 2013), by Julie Kibler, is the story of a road trip from Texas to Ohio and back prompted by Isabelle, an elderly white woman, who asks Dorrie, her thirty-something black hairdresser, to be her driver. The two are already friends, but there’s a lot about Isabelle that Dorrie doesn’t know. The friendship deepens when Isabelle reveals the reason for their trip.

Absalom’s Daughters (Henry Holt, 2016), by Suzanne Feldman, is another road-trip novel, this one involving two teenagers in 1950s Mississippi: Cassie, who’s black, and Judith, her white half-sister. When the girls learn that they have the same father, they decide to drive from Mississippi to Virginia to claim what they believe is their share of the family fortune he’s about to inherit. Along the way, they encounter incidents of racism, which also affects their budding relationship.

Melting the Blues (Gold Fern Press, 2016), by Tracy Chiles McGhee, differs from these first three novels in two respects: the author is black, and the friendship here is between two men. Augustus Lee Rivers, a black guitarist and farmer in fictional Chinaberry, Arkansas, dreams of hitting the big time in Chicago, even though this would mean leaving his half-white wife, Pearl, and their three children behind. David Duncan, a member of the town’s wealthiest white family, loves music, especially the bluesy tunes of Hummin’ Gusty Rivers, David’s nickname for his good friend Augustus. The year is 1957, and members of the “N. Double A.C.P.” are urging change in Chinaberry. Just as in Feldman’s Absalom’s Daughters (above), this novel has a touch of magical realism.

I feel very fortunate to have discovered these books. I’ve since met one of the authors, and all four of them are now my Facebook friends. Of course white authors can write about black characters, and vice versa!

But I’ll let New Yorker writer and critic Hilton Als have the final word here. While doing research for my next novel, I was looking through Sally Mann’s book of photographs, A Thousand Crossings (National Gallery of Art/Abrams, 2018), and, on page 167, came across the following passage by Mr. Als:

“I think the question should be both more pointed and more general: Who gets to speak for Americanness? To ask who gets to speak for blackness feels segregationist, as if black people, events, history, lore, voices, are somewhere ‘over there,’ separate from the larger issue of America as a whole. How can this be when blacks–like Native Americans, Latinos, women, Jews–are endemic to a country that has long tried shut them out?

I think the artists who ‘get to’ speak are those who do justice to the country’s complexity, in work that is as complex, dense, strange, and incomprehensible as the country that made them . . .”

—

Jill McCroskey Coupe is the award-winning author of two novels about unlikely friendships, Beginning with Cannonballs (2020) and True Stories at the Smoky View (2016), both published by She Writes Press. Her MFA in Fiction is from Warren Wilson College. A former librarian at Johns Hopkins University, Jill lives in Baltimore. Please visit her online at jillmcoupe.com and at www.facebook.com/jillmccroskeycoupe

Find her on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/jillmccroskeycoupe/

Follow her on Twitter https://twitter.com/coupe_jill

BEGINNING WITH CANNONBALLS

In the 1940s, in segregated Knoxville, Tennessee, Gail (white) and Hanna (black) shared a crib in Gail’s parents’ house, where Hanna’s mother, Sophie, was the live-in maid. When the girls were four, Sophie taught them to swim, and soon they were gleefully doing cannonballs off the diving board, playing a game they’d invented based on their favorite Billie Holiday song.

In the 1940s, in segregated Knoxville, Tennessee, Gail (white) and Hanna (black) shared a crib in Gail’s parents’ house, where Hanna’s mother, Sophie, was the live-in maid. When the girls were four, Sophie taught them to swim, and soon they were gleefully doing cannonballs off the diving board, playing a game they’d invented based on their favorite Billie Holiday song.

By the time they’re both in college, however, the two friends have lost touch with each other. A reunion in Washington, DC, sought by Gail but resented by Hanna, sets the tone for their relationship from then on. Marriage, children, and a tragic death further strain the increasingly fragile bond. How much longer can the friendship last?

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: On Writing