The Sentence

I, who love words so much, am surprised to find myself newly enchanted with the sentence as a unit of language. Sentences in all their delicious variety, some with many clauses, dipping in and out, amplifying a theme before it brings itself, sharply, to a halt. Or long sentences that make you think, having to puzzle out their meaning, like digging into a pomegranate to get the sweet, juicy seeds. Laborious, but usually worth it. Then there are the short, declarative sentences that command attention. Look up! they say.

The lowly sentence, which all of us use every day, is the building block of prose. It is the framework into which we fit all our lovely words, creating the rhythm and the tempo of our work. Our sentences are music, giving a sound to our creative impulse. They’re the time signature of the music we create with our words. Brief sentences are in 4/4 time, beating out their meaning with a regular clap. They follow the injunction of French author Stendhal, who said of writing, “I see but one rule: to be clear.” Let’s simply say what we mean, such writing proclaims. You can trust me. I’m not going to embellish anything.

This is the form I chose to use once in a story about my tense interaction with a car salesman. After I started bargaining he snapped, “We don’t deal with women who have printouts.” Then he called his manager. “Problem here.”

“What seems to be the problem?” the manager snarled at me.

“I’d just like to know the actual selling cost. Not the sticker price.”

“We have families!” He screamed. “To feed!”

“Fine, make a profit. I have a right to know dealer cost. And then I’ll add $500 for you.”

“I don’t bring my salespeople here to be abused. By people like you.”

People like me? A middle-aged woman with checkbook in hand. Eager to buy. Today.

“Get out!” he shouted.

As I passed their plate glass window I imagined the sound of shattering glass. Ah, if I’d only had a rock in my hand.

It was a simple story, one that resonated with women facing similar disrespect. Or with anyone often condescended to in public. The brief sentences of my account carried a blunt weigh. I wanted to bludgeon the reader as I’d been bludgeoned by the men’s hard voices. Men who’d rather lose a sale than be “Jewed down,” they said, by a woman in possession of facts.

Some writers prefer more complex, full-bodied sentences with which to express life’s ambiguities. Perhaps as we get older a bit of compassion for complexity is what many of us feel after the certainties of youth have fled. “Oh, if only I were Queen of the World,” I used to imagine in my twenties. “I’d make everything alright. No more war, no more poverty. I’d redistribute everything.” It took awhile to learn that creating economic equality isn’t quite that simple, and that deep-seated prejudices and distorted ideas are like weeds: you pull them up one season, but the next, there they are again. Persistent little devils. It’s difficult to communicate subtlety in brief sentences designed to stun the reader.

Now I’m more apt to want to seduce readers with language and invite them into a broad web of reasoning, hoping to parse a helpful truth. While my principles of equality remain as they were decades ago, my thinking has expanded, and to convey such growth I often need a longer elaboration. If I’m writing about the heartbreak of endless war in Afghanistan, for instance, and the anguish there, my short, direct sentences may not be able to adequately convey that particular geography of grief and hope. The resilience, decade after decade, of Afghanis who keep opening schools for girls only to have them brutally shut, shines such a light on the irrepressible buoyancy of the human spirit that it inspires me even as I mourn for generations of girls—and their brothers–who’ve known only war all their lives.

Sentences have the flexibility to function as either a blunt instrument or a nuanced argument. Their structures are infinite. Sentences can end with a period, an exclamation or question mark; they can contain one clause or two or three or even more. They may be injunctions, issuing commands. They may be questions, or fragments. They can sound demanding, pleading, joking, or mysterious, and much of the voice comes from their structure.

In writing prose we are often advised to vary sentence structure and length to hold reader interest. Whether we follow this advice depends on the rhythm we wish to create: the staccato effect of multiple short bursts of words, or a smooth lyrical sense, like a meandering river gently burbling over stones. Or maybe we want to pose questions, hoping to elicit reader curiosity.

Whatever sentence structures you choose, become aware of them as tools of your trade, as powerful as words in transmitting your meaning. Play around with different lengths. Try simple and then compound sentences to see how the tone shifts. Once you are conscious of the options, you have one more instrument at your disposal.

May your writing flourish, and all your sentences be grand!

# # #

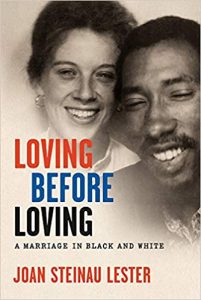

Joan Steinau Lester is an award-winning commentator, columnist, and author of five critically acclaimed books, including Mama’s Child and Black, White, Other. Her writing has appeared in such publications as USA Today, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Chicago Tribune, Cosmopolitan, and Huffington Post. Her memoir Loving Before Loving: A Marriage in Black and White is available for pre-order from University of Wisconsin Press (May 18, 2021).

LOVING BEFORE LOVING: A MARRIAGE IN BLACK AND WHITE, Joan Steinau Lester

“This book is the real deal, the way it was. A good book for folks to grow on. I love it! Bravo!”—Alice Walker, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Color Purple

Committed to the struggle for civil rights, in the late 1950s Joan Steinau marched and protested as a white ally and young woman coming to terms with her own racism. She fell in love and married a fellow activist, the Black writer Julius Lester, establishing a partnership that was long and multifaceted but not free of the politics of race and gender. As the women’s movement dawned, feminism helped Lester find her voice, her pansexuality, and the courage to be herself.

Committed to the struggle for civil rights, in the late 1950s Joan Steinau marched and protested as a white ally and young woman coming to terms with her own racism. She fell in love and married a fellow activist, the Black writer Julius Lester, establishing a partnership that was long and multifaceted but not free of the politics of race and gender. As the women’s movement dawned, feminism helped Lester find her voice, her pansexuality, and the courage to be herself.

Braiding intellectual, personal, and political history, Lester tells the story of a writer and activist fighting for love and justice before, during, and after the Supreme Court’s 1967 decision striking down bans on interracial marriage in Loving v. Virginia. She describes her own shifts in consciousness, from an activist climbing police barricades by day and reading and writing late into the night to a woman navigating the coming-out process in midlife, before finding the publishing success she had dreamed of. Speaking candidly about every facet of her life, Lester illuminates her journey to fulfillment and healing.

“Exceptional. It is a real challenge to write a memoir that is intellectually deep, psychologically

sophisticated, and politically principled that is also engaging, accessible, funny, and tender. Loving before Loving certainly is all that. What a remarkable ride.” —Becky Thompson, author of A Promise and a Way of Life

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips