On Writing and Early Motherhood

On Writing and Early Motherhood

Photo by Rosalind Hobley

‘You’ll never have time to read.’ The first time I heard it, it sounded strange, remote from my life. The second, third times, it began to sink in. And there were more. ‘You’ll find it a challenge just to get through the day.’ ‘You’ll develop “mummy brain.”’ If you’ve ever been expecting a baby, you’ll probably have heard similar predictions.

I know these comments weren’t meant to be as discouraging as I found them. The women who voiced them – all mothers themselves – were trying to reassure me that, after giving birth, it would be normal for me to struggle to do many of the things I took for granted before, and that I shouldn’t feel bad about it.

But I did feel bad about it. My problem was that, not only would I be delivering my baby in the summer, I had a book to deliver in the autumn. I’d pitched a group biography about six unlikely Victorian superstars, whose once immense fame and cultural influence was founded on their apparent abilities to contact the dead. With American and British women as my featured subjects, the book not only required substantial research on both sides of the Atlantic, it was projected to be over 80,000 words. Never mind finding the time to read, I also needed to find time to write.

With hindsight – and with a finished copy of Out of the Shadows safely on a shelf in my study – I now know that I spent far too much of my pregnancy worrying about the things other people said. However, I was at least able to channel this worrying into a couple of practical steps, which helped me feel that I had a semblance of control over my destiny.

Crucially, I made a plan to which I broadly stuck, mapping out all the research that needed to be undertaken – particularly focusing on anything that involved significant travelling – and how much of the book had to be written before my baby arrived. As a result, I was able to achieve my goal of completing a first draft before I gave birth. In fact, I managed this with a whole luxurious week-and-a-half to spare! This gave me a few glorious days of rest before a labour that lasted a gruelling 30 hours.

The other thing I did was discuss my situation frankly with the people who would be directly involved in bringing my book to completion. My publisher agreed to push the delivery date for the manuscript back a few months, to winter. I also made it clear that, going forward, I would need to fit my writing around childcare responsibilities and that, although I’d be able to meet every commitment, I would need plenty of advance warning about deadlines and the like. Additionally, since I have a partner, he and I came up with our own plan about how we would share the care of our baby while making sure that we each had time to work, too.

After the joy of my daughter’s arrival, I took the summer off, but by the autumn I was back at my study desk – or in the reading rooms of academic libraries with a breast pump in my locker – for at least part of each weekday. I was lucky that my husband was able to take shared parental leave, and that he worked very different hours to me. This meant that he was able to keep doing a daily share of the childcare even once he’d returned to his job. Although there were days, especially if my little girl had kept me up for hours at night, when keeping to this routine was exhausting, the process of revising the book, and seeing it gradually improve with each draft, kept me going.

I was also pleasantly surprised to discover that so-called ‘mummy brain’ was not merely the sorry state of absentmindedness of which I’d been warned. Of course, especially given the early sleep deprivation, there were times when I found myself missing appointments or forgetting where I’d put things. On the other hand, I became super-organised with my time and, rather than my brain turning to mush, for me anyway, motherhood gave me a different perspective on the world and opened up new parts of my creativity.

I also began to pay fresh attention to the careers of women who combined caring roles with creative work. And I didn’t have to look further than my current research for one such example. Victoria Woodhull, a childhood clairvoyant who became a rising star on Wall Street and America’s first female presidential candidate, also wrote for and edited a weekly newspaper.

Woodhull combined these achievements with mothering two children – including a son with profound learning disabilities, whom she looked after at home until the end of her life. In more recent times, commenting on how motherhood can actually focus the mind, the poet Kate Clanchy has said: ‘I found if I had three hours, and really concentrated, that was enough.’ Author Alice Walker, in contrast, has suggested that such concentration has its limits. Once asked whether female artists should have children, she replied that they should, ‘assuming this is of interest to them—but only one. Because with one you can move. With more than one, you’re a sitting duck.’

I very much hope that, for me, Walker’s words will prove as untrue as the other warnings I received two-and-a-half years ago. In six weeks from now, I am expecting a son – a fitting end, perhaps, to my journey of the past few years, with its twinned experiences of carrying my babies and my hopes for my book, giving birth to both, and carrying on.–

–

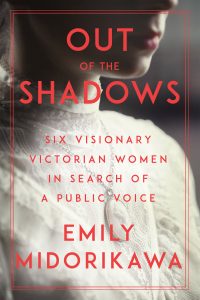

Emily Midorikawa is the author of Out of the Shadows: Six Visionary Victorian Women in Search of a Public Voice, published by Counterpoint Press in May 2021. She is also the co-author of A Secret Sisterhood: The Hidden Friendships of Austen, Brontё, Eliot and Woolf (written with Emma Claire Sweeney, and with a foreword by Margaret Atwood). Emily is a winner of the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize. Her journalism has been published in, among others, the Daily Telegraph, the Paris Review, The Times and the Washington Post. She teaches on the writing programme at New York University London.

Follow Emily on Twitter https://twitter.com/EmilyMidorikawa

Website https://emilymidorikawa.com/

Out Of The Shadows: Six Visionary Women In Search of a Public Voice

Out of the Shadows: Six Visionary Victorian Women in Search of a Public Voice tells the stories of six enterprising women whose supposedly clairvoyant gifts granted them fame, fortune, and astonishing levels of influence, as they crossed rigid boundaries of gender and class as easily as they passed between the realms of the living and the dead.

Out of the Shadows: Six Visionary Victorian Women in Search of a Public Voice tells the stories of six enterprising women whose supposedly clairvoyant gifts granted them fame, fortune, and astonishing levels of influence, as they crossed rigid boundaries of gender and class as easily as they passed between the realms of the living and the dead.

The Fox sisters inspired some of the era’s best-known political activists and set off a transatlantic séance craze. While in the throes of a trance, Emma Hardinge Britten delivered powerful speeches to crowds of thousands. Victoria Woodhull claimed guidance from the spirit world as she took on the millionaires of Wall Street before becoming America’s first female presidential candidate. And Georgina Weldon narrowly escaped the asylum before becoming a celebrity campaigner against archaic lunacy laws. Drawing on diaries, letters, rarely seen memoirs and texts, Emily Midorikawa illuminates a radical history of female influence that has been confined to the dark until now.

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips