Readers – Should Novelists Protect Them?

Someone in the publishing trade said to me, “A good writer cannot protect their readers or their characters.”

Someone in the publishing trade said to me, “A good writer cannot protect their readers or their characters.”

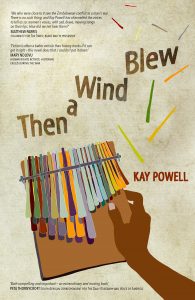

At the time, I was working on the outline for the story that became Then a Wind Blew – published by Weaver Press (Zimbabwe) and told by three women caught up in the final brutal years of the Rhodesia/Zimbabwe war in the late 1970s – and I was musing about the sensitivities of the potential readership.

At that stage, the concept of ‘protecting your characters’ was an alien one. I hadn’t written fiction before and was unaware of the way the characters you create tend to want to let go of your hand at some point and evolve in ways you hadn’t planned. And, for the novel to work, you have to let them go.

But ‘protecting your readers’ was something I’d given thought to. I wanted to tell a story about a time and place I knew well, a story that would be difficult to read in parts, but would be as true to people and events, attitudes and actions, as my research and my memory dictated.

The potential readership would be very divided. In one corner, those who’d been caught up in the war, as fighters, supporters, victims, onlookers. In the other corner, those who knew little, if anything, about the war or the country in which it played out. So, differences in knowledge and understanding within the readership would be immense.

More than that, the knowledge held by the group who’d been in or close to the war would have been coloured by propaganda. All wars come with propaganda, this one was no different. I’m talking here not only of the powerful propaganda machines built by the white government and its opposing black guerrilla forces, but also of the propaganda put out by the foreign media, which often took sides and suppressed what showed its ‘side’ up in a poor light. Thus, for years afterwards, many people still had difficulty separating fact from propaganda fiction. Some, whatever ‘side’ they were on, still do.

By the time I’d written the final outline of Then a Wind Blew, and was ready to start writing, I’d done a great amount of research, re-reading everything I had on the subject, reading all that the British Library and other sources had to offer on the subject (including memoirs of people who’d fought in the war, on either ‘side’), and meeting and corresponding with people who’d researched the period. I felt as certain as I could be of the facts. Putting flesh on the bones of those facts meant creating a credible plot and a cast of credible characters, and for that I drew largely on first-hand experience.

It wasn’t long before I started to ask myself questions about whether I should compromise on this character, that fact, so as to soften the edges a little, paint a less painful picture, a less distasteful character. I hadn’t set out to shock or upset, only to tell the truth as I now understood it, but whenever I tried to temper events or dilute characters, the prose rebelled, sounded contrived.

At that point, someone said, “A good writer cannot protect their readers or their characters.” And I saw that I had to rise above ‘protecting’ my readers and stay true to my characters and to the time and place they inhabited. And so on I went, knowing that if/when the novel was published, some would find in it much they knew but would have preferred left unsaid, others would learn new things and either wish they hadn’t or be glad they had. And there’d be those, inevitably, who’d continue to dispute the facts. “Lay the worst atrocities at their door, not ours.” “There was no sexual harassment in the camps.” “The story that we distributed lethally poisoned clothing among them is nonsense.” “Cutting off the lips and limbs of own people? – no, that was not our way.” And so on.

War creates its own culture. It sucks everyone within reach into that culture, distorting norms, corrupting values, infecting everything, including truth. For some, as the author Brian Chikwava noted in his review of Then a Wind Blew, “coming to terms with the realisation that the capacity for brutality is not an exclusive feature of one group of people can be overwhelming.”

When Then a Wind Blew was published earlier this year, typical responses from readers who knew little about the war or the country included: “A thought-provoking and memorable book, which both shocked and educated me in relation to the history of Rhodesia/Zimbabwe.” “It exposed to me how little I knew of life in that country at the time, something I should really rectify.”

Of those readers who’d been close to the war, some found the book enlightening and asked why they hadn’t known more. “It’s not an easy book to read, but it shouldn’t be. It should make us uncomfortable. It should be harrowing. Why didn’t we know more about what was happening?” wrote a book blogger who’d assumed she’d known quite a lot about what was happening.

Also wishing he’d known more was Matthew Parris (correspondent for The Times, brought up in Rhodesia): “We who were close to it saw the Zimbabwean conflict as a man’s war. There is no such thing, and Kay Powell has channelled the voices to tell us so: women’s voices, with sad, brave, moving songs on their lips. How did we not hear them?”

Among other readers for whom Zimbabwe was – and in some cases still is – home, the issue was not what they did or didn’t know, but whether or not I’d offered a balanced picture.

Some said ‘no’. “I got the impression that you ‘had an agenda’ to present the colonization of the country as nothing but a Bad Thing, that the only good whites were expats, and that all the blacks were subjugated into poverty.” “In her novel she calls the whites ‘settlers’ – you can tell what side she was on.”

Some said ‘yes’. “This was an excellent albeit distressing read… Kay Powell writes like an artist who paints not because she wants to sell her paintings, but because it is an expression of truth.” “Fiction is often a better vehicle than history books if it can get it right – this novel really does that.” “The tragedy of the war for Zimbabwean independence seen from both sides – a great work.”

There were also those who could not read the book because the idea of going back to those times was too distressing. Interestingly, the people I know personally who have reacted this way all still live in Zimbabwe and are all women. Among them is Judith Todd (daughter of a former Prime Minister, Sir Garfield Todd; she was imprisoned by the Smith government). For her and others in this group, the wounds of that war are still raw, and seeing its repercussions still playing out all around them doesn’t help the healing.

The truth can be difficult to absorb and difficult to tell. That was certainly the case with this novel. But the feeling I got when I’d finished writing it, knowing that I hadn’t compromised on the characters or the readership, was a good one. And it has stayed with me.

Iris Murdoch knew this feeling when she wrote: “Art is the telling of truth and is the only available method for the telling of certain truths.”

—

Watch a SHORT VIDEO of an interview with the author, Kay Powell, and readings of excerpts from the book by leading actors in Zimbabwe (Charmaine Mujeri and Michael Kudakwashe) and the UK (Robin Ellis and Christine Kavanagh) here: https://youtu.be/WclsQb6Ej8U

‘We who were close to it saw the Zimbabwean conflict as a man’s war. There is no such thing, and Kay Powell has channelled the voices to tell us so: women’s voices, with sad, brave, moving songs on their lips. How did we not hear them?’

MATTHEW PARRIS Columnist for The Times, and radio and TV presenter

‘Kay Powell’s novel about women trapped in the brutality of war is both compelling and important – an extraordinary and moving book.’

PETA THORNYCROFT South African-based correspondent for The Daily Telegraph and Voice of America

‘A fascinating, ambitious and brave novel that will leave a lasting impression on the reader.’

BRIAN CHIKWAVA Winner of 2004 Caine Prize, author of acclaimed Harare North (Jonathan Cape)

‘This novel asks us to look away from images of war as an expression of male heroism in order to hear women tell the bitter truths about war.’

BRITTLE PAPER US online magazine for African literature

Kay Powell was born in Zambia and grew up in Rhodesia. In 1968 she went to university in the UK and became a social worker. She returned to Rhodesia for a few years in the 1970s, and her two daughters were born there. After a stint at Faber & Faber in London, she returned to Zimbabwe in 1981, first working for Macmillan, then co-founding Quest, a publisher of non-fiction titles.

Kay Powell was born in Zambia and grew up in Rhodesia. In 1968 she went to university in the UK and became a social worker. She returned to Rhodesia for a few years in the 1970s, and her two daughters were born there. After a stint at Faber & Faber in London, she returned to Zimbabwe in 1981, first working for Macmillan, then co-founding Quest, a publisher of non-fiction titles.

Emigrating to England in 1988, Kay set up an agency to provide publishing services to international development organisations. In 2008, her book on the use of English in the workplace, What Not To Write, was published by Talisman, Singapore, and became a bestseller. Then a Wind Blew is Kay’s first novel. She lives near Cambridge, UK, with her husband, who is also a novelist.

For more, see: kay-powell.net and Twitter @JIMandKAYPowell

THEN A WIND BLEW

Then a Wind Blew is set in the final months of the war in Rhodesia, before it became Zimbabwe, and the story unfolds through the voices of three women. Susan Haig, a white settler, has lost one son in the war and seen her other son declared ‘unfit for duty’. Nyanye Maseka has fled with her sister to a guerrilla camp in Mozambique, her home village destroyed, her mother missing. Beth Lytton is a nun in a church mission in an African Reserve, watching her adopted country tear itself apart.

The three women have nothing in common. Yet the events of war conspire to draw them into each other’s lives in a way that none of them could have imagined. This absorbing and sensitive novel develops and intertwines their stories, showing us the ugliness of war for women caught up in it and reminding us that, in the end, we all depend on each other.

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips