Rethinking Revenge: Injustice, Empathy, and Common Ground on a Bridge over the Thames

The plot for Down a Dark River leapt at me from a contemporary story that I couldn’t put out of my head.

The plot for Down a Dark River leapt at me from a contemporary story that I couldn’t put out of my head.

Some years ago, I read an article about race and the law in the US that included an account of a young Black woman in the South who jaywalked across a quiet street. She was hit by a white man who was driving too fast and under the influence of alcohol, although under the legal DUI limit. Her injuries kept her in the hospital for months, but a judge awarded her damages of only $2,000—ostensibly because she had been jaywalking. The appalling injustice clawed at me. But even more striking to me was the extralegal fallout: her angry father threatened not the judge but the judge’s daughter.

I could only imagine that the father did so to make the judge understand what it was to almost lose a daughter. As I continued to reflect on this story, I began to consider that revenge is significantly more complicated than the brief phrase “an eye for an eye” suggests.

In this young woman’s case, legal justice failed at the level of the symbol (which is what monetary compensation, or language such as a verbal apology, or a guilty verdict is because none of them materially reverses the damage of broken bones). On one level, the father’s “revenge” can be read as an attempt to communicate his painful experience not via language (which is symbolic and didn’t work), but via physical violence (which is material) to someone who, out of a lack of empathy, or out of ignorance or willfulness, refused initially to acknowledge it.

So what is it about revenge that satisfies us—at least in our imaginations? Why does a desire for revenge often feel so deep that it razors our hearts? What precisely is satisfying about the fantasy of causing someone else the same pain we are feeling or felt? (Why do I name villains in my books after girls who tormented me in middle school? Do I imagine that those girls will feel a pang of guilt or regret, a mild version of the pain they once caused me?)

In her insightful work on intimacy, the psychologist and researcher Brené Brown says that our deepest need is for communication and connection to others, which includes both speaking our truth and being seen and heard by another. Given that the desire for revenge feels awfully deep when we’re in it, is it possible that revenge is sometimes a desperate, indirect, second-rate, non-verbal (and problematic) attempt at communicating and connecting with someone who is refusing to acknowledge our experience, our pain, our reality?

I’ve come to believe that when we are in pain, particularly if our pain is caused by someone else, there is part of us that still wants to connect and communicate with that person, to have him or her see and hear us. We want that person to feel what we are feeling—literally, to stand in our shoes, to stand on common ground with us. Empathy is the voluntary response to this wish, of course. In empathizing, we willingly draw upon whatever similar experiences we have had, combined with our imagination, to understand someone else’s situation. However, revenge—metaphorically shoving someone into our shoes, forcing someone to stand beside us on common ground—is what happens when empathy fails.

I’ve come to believe that when we are in pain, particularly if our pain is caused by someone else, there is part of us that still wants to connect and communicate with that person, to have him or her see and hear us. We want that person to feel what we are feeling—literally, to stand in our shoes, to stand on common ground with us. Empathy is the voluntary response to this wish, of course. In empathizing, we willingly draw upon whatever similar experiences we have had, combined with our imagination, to understand someone else’s situation. However, revenge—metaphorically shoving someone into our shoes, forcing someone to stand beside us on common ground—is what happens when empathy fails.

In mysteries, we authors tend to work toward an ending that sets the world right—often through a combination of “legal justice” and “poetic justice.” Now, a fictional villain might be so wealthy as to be beyond the reach of the law courts, so “legal justice” fails. But “poetic justice” can be even more satisfying: out of horror at what the villain has done, his heiress wife deserts him, and he is rendered as destitute and powerless as his victim once was, perhaps forced to beg for work or mercy from the very person he once injured.

In Down a Dark River, I wanted to explore the role that empathy plays in allaying the desire for revenge, and to explore “legal justice” and “poetic justice” in 1870s London, a city full of inequities and cruelty.

My novel is shaped by my belief in the transformative power of empathy, which for me begins with remembering our similarities—namely, that most of us are doing the best we can; and while we all make mistakes, we are evolving beings, and it usually isn’t fair to judge someone by their single worst action. (Frankly, if I were judged solely by my worst actions, I’m not sure I’d have any friends.) Finding empathy requires that we resist reducing people to one aspect of their identity and avoid those ugly binary terms of “us” versus “them.”

Often this simply requires us finding common ground—which is one reason I chose Blackfriars Bridge over the Thames for the most important scene in Down a Dark River. One man speaks, and another listens with empathy—and in my fictional world, the craving for revenge diminishes, a measure of justice is found, and as the dark river sweeps under the bridge, there is some hope of healing for those left behind.

—

Karen Odden earned her PhD in English from New York University and subsequently taught literature at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She has contributed essays to numerous books and journals, written introductions for Victorian novels in the Barnes & Noble Classics series, and edited for the journal Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge UP). Her first three Victorian mysteries, all set in 1870s London, have won awards for historical fiction and mystery. Her fourth, Down a Dark River, will be published in November 2021 by Crooked Lane Books. A member of Mystery Writers of America and Sisters in Crime and the recipient of a 2021 grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts, Karen lives in Arizona with her family and her rescue beagle, Rosy.

Connect with Karen at www.karenodden.com.

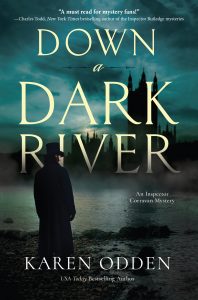

DOWN A DARK RIVER

In the vein of C. S. Harris and Anne Perry, Karen Odden’s mystery introduces Inspector Michael Corravan as he investigates a string of vicious murders that has rocked Victorian London’s upper crust.

In the vein of C. S. Harris and Anne Perry, Karen Odden’s mystery introduces Inspector Michael Corravan as he investigates a string of vicious murders that has rocked Victorian London’s upper crust.

London, 1878. One April morning, a small boat bearing a young woman’s corpse floats down the murky waters of the Thames. When the victim is identified as Rose Albert, daughter of a prominent judge, the Scotland Yard director gives the case to Michael Corravan, one of the only Senior Inspectors remaining after a corruption scandal the previous autumn left the division in ruins. Reluctantly, Corravan abandons his ongoing case, a search for the missing wife of a shipping magnate, handing it over to his young colleague, Mr. Stiles.

An Irish former bare-knuckles boxer and dockworker from London’s seedy East End, Corravan has good street sense and an inspector’s knack for digging up clues. But he’s confounded when, a week later, a second woman is found dead in a rowboat, and then a third. The dead women seem to have no connection whatsoever. Meanwhile, Mr. Stiles makes an alarming discovery: the shipping magnate’s missing wife, Mrs. Beckford, may not have fled her house because she was insane, as her husband claims, and Mr. Beckford may not be the successful man of business that he appears to be.

Slowly, it becomes clear that the river murders and the case of Mrs. Beckford may be linked through some terrible act of injustice in the past—for which someone has vowed a brutal vengeance. Now, with the newspapers once again trumpeting the Yard’s failures, Corravan must dredge up the truth—before London devolves into a state of panic and before the killer claims another innocent victim.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips