Why Writing Can Save Lives

Inspired by the many teachers who mentored and encouraged me during my own school years, I became an educator and enjoyed a rewarding fifty-year career, teaching upper elementary school students as well as preparing future teachers in my role as a college professor. Fifty years sped by, as I was propelled by a mission: to “pay back” those angel-teachers who had influenced me and who made me feel important every day. Even though I was a poor kid from the projects, they sent me the message that I could do anything I put my mind to. And so, I did. My teachers were my role models, my mentors, and I felt it important for me to treat each of my own students as my teachers had treated me: with dignity, respect, and high expectations.

Inspired by the many teachers who mentored and encouraged me during my own school years, I became an educator and enjoyed a rewarding fifty-year career, teaching upper elementary school students as well as preparing future teachers in my role as a college professor. Fifty years sped by, as I was propelled by a mission: to “pay back” those angel-teachers who had influenced me and who made me feel important every day. Even though I was a poor kid from the projects, they sent me the message that I could do anything I put my mind to. And so, I did. My teachers were my role models, my mentors, and I felt it important for me to treat each of my own students as my teachers had treated me: with dignity, respect, and high expectations.

Upon retirement, I signed up for a Creative Non-Fiction class, remembering how much I loved to write, starting with my stint as Managing Editor of my junior high school newspaper, The Wilsonian, and continuing throughout my professional career. In one of the early classes, the teacher presented the prompt, “Hair.” I put pen to paper and out poured a poem that I later titled “The Beating.”

The first beating comes when I am seven.

“You’re just like your father,” she screams.

“No good. Taking, taking.”

Her voice is shrill. She snatches me by my arm.

Yanks me off the crate.

Flings me onto the floor.

Kicks me in my side.

I curl into a ball and cry.

Whoosh! A flood escapes from between my legs.

I piddle all over the floor.

She kicks me again and

grabs my hair as she

pulls me through

the wet mess.

wiping the floor

with me,

a mop.

My voice broke as I read my poem to the others in the writing class. It was then that I realized it was time to write my memoir. I was ready. Finally.

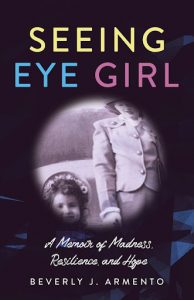

A decade after “The Beating,” Seeing Eye Girl: A Memoir of Madness, Resilience, and Hope is complete and will launch on July 5, 2022. It’s a story of growing up in a physically and emotionally abusive home, the complex story of survival, of inventing ways of being resilient and of seeking glimmers of hope. It’s the story of Strong Beverly, who showed up at school and church: outgoing, gregarious, smart, funny, a leader—always with a smile on her face and a skip in her step. But at home she was Weak Beverly, cowed by her mother’s rage and violence. There she was silent, obedient, cautious, on guard, and a caretaker for her siblings and the household.

While Seeing Eye Girl is uniquely my story, my way of surviving a chaotic childhood, I realize there are many others whose lives resonate with mine: that is, they are also among the Invisible Walking Wounded, those who present themselves to the world with a cheerful façade while hiding painful secrets and the emotions and fears that come from “Adverse Childhood Experiences” or ACEs.

Adverse Childhood Experiences include emotional, physical, sexual abuse; living in a home where alcohol, drug addiction, or violence occurs; losing a parent or guardian; being food-insecure, and many other factors that contribute to stress, anxiety, and depression. When the Surgeon General of the United States, Vivek Murthy (December, 2021) says there is a mental health crisis among the nation’s children and young adults, it is time to pay attention. The Covid-19 Pandemic has resulted in academic, attendance, access to education issues for many children, especially the poorest, as well as increased anxiety, social isolation, and depression. Addiction rates have increased during the pandemic, and almost 200,000 children/adolescents in the United States have lost a parent or caregiver to Covid-19 over the last several years (December 9, 2021, Report by Covid Collaborative, CDC).

My growing-up years were from the 1940s-1960s. Then, there was little attention to ACEs, both in the literature and in practice. Today, researchers and practitioners are finally asking: What are the relationships between Adverse Childhood Experiences and cognitive, health, and behavioral issues? And what are the implications for practice in medical, educational, community, religious settings?

During the late 1990s, the CDC in collaboration with Kaiser Permanente, conducted one of the first major studies of the effects of ACEs (results published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 1998, 14(4): “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults”). Using a self-report questionnaire, adult respondents were asked about seven categories of adverse childhood experiences: psychological, physical, or sexual abuse; violence against the mother; or living with household members who were substance abusers, mentally ill, suicidal, or ever imprisoned. More than half of the respondents (almost 10,000) reported being exposed to at least one of these ACEs, with one fourth of the respondents being exposed to two or more ACEs. The higher the exposure to ACEs, the greater the health risk of the person for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, suicidal attempts, sexually transmitted diseases, heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and obesity.

Since the time of this initial investigation on ACEs and adult health, many interdisciplinary researchers have expanded the scope of study to include the effects of childhood trauma on developmental issues, cognitive functioning, school readiness, brain development, mental health problems, and memory deficits (see especially the work of Sara McLean at the Australian Institute for Family Studies). Currently there is little research on the effects of interventions on the recovery of cognitive or memory skills or on the strengthening of resilience in children living in stressful homes, but these are emerging fields of inquiry.

Since the start of the worldwide Covid-19 Pandemic, new researchers have examined the effects of the pandemic on students, schools, teachers, family structures, and communities. In addition, a number of interventional programs have been developed to assist students who have fallen behind academically or who suffer from depression during long periods of social isolation. The many stress factors originating from the pandemic, the rise in opioid addictions, and the increase in suicides only add to the ongoing toxic factors that have long brought heartache to children and adults. In 2021, more people around the world googled “how to maintain mental health” than ever before.

The Surgeon General’s “crisis” announcement called for a swift and coordinated response to mental health challenges in children and young adults. However, such responses are hard to come by, as trauma occurs behind closed doors and many young people adapt by suppressing their sorrow and despair and not talking about their abuse. Thus, the true size of the problem is really unknown. In addition, large scale approaches to mental health, changes in medical care, teacher/mentor preparation, the structure and nature of schooling and parent-education take resources and political will. For example, there is no national directory of children who have lost their parents to Covid, and the simplifying of the Suicide Hotline (from a 10 to a 3-digit code—988) occurs state by state, with approval followed by the need for funding. Thus far, only a handful of states have passed or even introduced legislation to build their 988 systems.

Here is not the place to fully explore the literature or discuss the implications for practice, but I did want to give you a sense of the size and nature of the issues potentially raised by Seeing Eye Girl. I don’t portend to represent or speak for those many Invisible Walking Wounded who are hurting and hiding their trauma behind smiles. I can only tell one story, my own. But by telling this story, my hope is that it will prompt us into larger discussions about the nature of Adverse Childhood Experiences and the implications for families, educators, medical professionals, and community agencies. How can we help parents, teachers, and community leaders be sensitive to and recognize trauma in children, and how can we create supportive, caring environments for young people where they can practice resilience skills and develop meaningful relationships with one another and with adults?

While teachers were my primary mentors, schools and educators cannot carry the total burden posed by young people traumatized by adverse childhood experiences. We’ll need a village of caring adults who are willing and able to show kindness, at the minimum, to the many Invisible Walking Wounded amongst us.

—

Beverly J. Armento is Professor Emerita at Georgia State University and holds degrees from The William Paterson University, Perdue University, and Indiana University. Seeing Eye Girl: A Memoir of Madness, Resilience, and Hope is her debut book, and will be published by She Writes Press on July 5, 2022. Find out more about her at www.beverlyarmentoauthor.com.

Seeing Eye Girl: A Memoir of Madness, Resilience, and Hope

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

As the “Seeing Eye Girl” for her blind, artistic, and mentally ill mother, Beverly Armento was intimately connected with and responsible for her, even though her mother physically and emotionally abused her. She was Strong Beverly at school—excellent in academics and mentored by caring teachers—but at home she was Weak Beverly, cowed by her mother’s rage and delusions.

As the “Seeing Eye Girl” for her blind, artistic, and mentally ill mother, Beverly Armento was intimately connected with and responsible for her, even though her mother physically and emotionally abused her. She was Strong Beverly at school—excellent in academics and mentored by caring teachers—but at home she was Weak Beverly, cowed by her mother’s rage and delusions.