From Your Friend, Carey Dean Letters from Nebraska’s Death Row: Excerpt

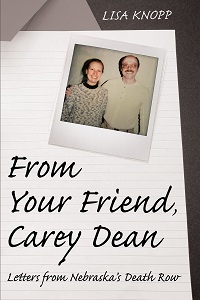

Lisa’s newest book, From Your Friend, Carey Dean: Letters from Nebraska’s Death Row (2022), is a memoir/biography. In 1995, when Lisa visited Nebraska’s death row with other death penalty abolitionists, she became acquainted with one of the inmates.

Lisa’s newest book, From Your Friend, Carey Dean: Letters from Nebraska’s Death Row (2022), is a memoir/biography. In 1995, when Lisa visited Nebraska’s death row with other death penalty abolitionists, she became acquainted with one of the inmates.

For the next 23 years, through visits, phone calls, and letters, a remarkable, platonic friendship flourished between Lisa, an English professor, and Carey Dean Moore, who’d murdered two Omaha cab drivers in 1979 and for which he was executed by lethal injection in 2018.

From Your Friend, Carey Dean, tells two other stories, as well. One is that of a broken correctional system (Nebraska’s prisons are overcrowded, understaffed, and underfunded, and excessive in their use of solitary confinement), and what it’s like to be incarcerated there, which Carey frequently spoke and wrote about. The other is the story of how a double murderer was transformed and nourished by his faith in God’s promises. Though Carey and Lisa were different types of Christians (he was a Biblical literalist and an evangelical; she is a Biblical contextualist with progressive leanings), they shared an abiding faith in God’s love and grace.

EXCERPT

From the Preface

I’d had no intention of writing a book about my friend until the last several months of his life, so it never occurred to me to follow up on some of the subjects that he had written about, either in face-to-face conversations or in my return letters. But that’s the way it is with personal correspondence. If he’d written about four or five topics in one of his letters, I might respond to but a few of those items and devote the rest of my letter to what was going on in my life. Carey did the same when answering my letters. When I drafted the book, I encountered many instances when it seems I should have known something that I didn’t. When he was in solitary confinement, did he have his Bible with him or not? What became of the correctional officer who Carey said had “poisoned” the water jugs that the men on death row drank from? During his last few months, Carey answered my questions until we ran out of time. . . .

During the last three months of Carey’s life, when we knew that he would not fight his pending execution, I wrote fast drafts—sketches, really—of nine chapters of the book so that I could present, for his scrutiny, an annotated table of contents. He weighed in on the titles, on what I proposed to cover in each chapter. And he advised me on how to approach the material: “If there’s anything juicy you might like to write about it, just ask . . . It can’t hurt. You should write about ‘some’ sensitive areas from both of us, which should keep readers interested and some comical or funny things [ . . . ]. What do you think?” (June 20, 2018).

Early in the writing process, I realized that I couldn’t just tell Carey’s story. Because our letters chronicle the story of a friendship, I had to include myself. Consequently, the book had to be a blend of biography and memoir, with the balance weighted more toward the former than the latter. For the most part, I expose myself in order to reveal my subject or our friendship. I kept copies of fewer than 20 percent of the letters that I wrote to Carey, so it was challenging to know what to say about myself. Fortunately, before Carey responded to my letters, he quoted a sentence or two of mine so that I’d remember what I’d written to him. This helped me recall “who I was” at different points in our long friendship. . . .

I went into this project not knowing if my subject would be dead or alive when I wrote the last page. Though Carey and I knew that an execution would have provided the tidiest ending, I assured him that he didn’t have to die for me to finish the book. To end with him, a sixty-year-old man who’d spent thirty-eight years on death row, watching as yet another execution date came and went, is an ending that would have represented his life as long as I’d known him, as well as the circumstances of others in Nebraska and beyond awaiting the fulfillment or commutation of their death sentences. In fact, when it seemed more likely than not that his execution would be stayed, I drafted a final chapter called “Sixty,” which was Carey’s age throughout most of 2018. I thought that when I completed that chapter, he would have received yet another stay and have returned to what he called “living in limbo.” In the final pages of that book, I would have explored how that made him feel. But that wasn’t the ending that he and I were given.

The most vexing question I had to answer during the writing was, who was I? A friend who wanted to tell the life story of a man who inspired her so that others would be inspired by it, too? An activist who had seized an opportunity to address a social issue in order to effect change? An artist who took pleasure, as Annie Dillard said, in fashioning a text from the material at hand? Or an opportunist who was using a friend’s afflictions as the subject of a book with her name on it? Perhaps I was all of these.

On the day of Carey’s execution, I knew no peace until that evening, when I started writing the final chapter. Then, I knew with clarity and certainty who I was. I was the friend who wanted to commemorate a remarkable person and turn his suffering into good. I was the activist who wanted to end capital punishment in Nebraska, the United States, and the world. And I was the artist who found relief and comfort from a crushing sorrow by fashioning a text about it.

—

Lisa was born and raised in Burlington, Iowa, a Mississippi River town. She was educated at Iowa Wesleyan College, Western Illinois University, and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Since 2005, she’s been a professor of English at the University of Nebraska-Omaha where she teaches courses in creative nonfiction, including food writing, travel writing, and a seminar in experimental forms. She’s a certified Reiki practitioner, and she enjoys mentoring children and adults at Heartland Big Brothers Big Sisters, Lincoln Literacy, and TeamMates Mentoring Program. Lisa lives in Lincoln, Nebraska with her two cats, Morwenna and Janko Noam Chomsky.

Lisa was born and raised in Burlington, Iowa, a Mississippi River town. She was educated at Iowa Wesleyan College, Western Illinois University, and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Since 2005, she’s been a professor of English at the University of Nebraska-Omaha where she teaches courses in creative nonfiction, including food writing, travel writing, and a seminar in experimental forms. She’s a certified Reiki practitioner, and she enjoys mentoring children and adults at Heartland Big Brothers Big Sisters, Lincoln Literacy, and TeamMates Mentoring Program. Lisa lives in Lincoln, Nebraska with her two cats, Morwenna and Janko Noam Chomsky.

Category: On Writing