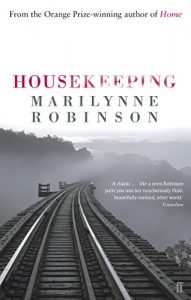

The Present Absent and the Figurative Literal: A Craft Lesson from Marilynne Robinson’s Classic Novel Housekeeping

The Present Absent and the Figurative Literal:

A Craft Lesson from Marilynne Robinson’s Classic Novel Housekeeping

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson has been hailed a classic, defining the contemporary novel for writers and readers of our time. First published in 1980, the book, a debut novel, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and awarded the PEN/Hemingway Award for best first novel. Using female archetype and metaphor in a different sort of coming-of-age story, the novel informed a generation of writers and readers in its use of clean simple style that somehow captured so many layers of complexity in its seemingly transparent prose and characterization of female coming-of-age and identity bathed in cosmic realism. In the novel’s cosmic realism, thought (interiority) holds dominance, influence, and authority over action (externalization) and the connection among primary characters is defined by loss, trauma, and absence in a way to make life seem transient and people ephemeral.

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson has been hailed a classic, defining the contemporary novel for writers and readers of our time. First published in 1980, the book, a debut novel, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and awarded the PEN/Hemingway Award for best first novel. Using female archetype and metaphor in a different sort of coming-of-age story, the novel informed a generation of writers and readers in its use of clean simple style that somehow captured so many layers of complexity in its seemingly transparent prose and characterization of female coming-of-age and identity bathed in cosmic realism. In the novel’s cosmic realism, thought (interiority) holds dominance, influence, and authority over action (externalization) and the connection among primary characters is defined by loss, trauma, and absence in a way to make life seem transient and people ephemeral.

Now that the young writers Housekeeping influenced have emerged and come of age and now that so much time has passed since the novel was first published in 1980 and notions of gender are so much more complex in terms of contemporary literature and society, how does Housekeeping hold up today? Is it still as influential as it once was, and what does Marilynne Robinson offer in terms of craft and influence for writers today?

In the spring of 2022, I addressed these questions when I was presented a talk in an official AWP (Association of Writers & Writing Programs) Panel in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This panel was titled “Retrograde Radical: Marilynne Robinson’s Cosmic Realism.” In this panel, innovative novelists, all seasoned fiction workshop leaders, discussed how Robinson achieves her remarkable effects, engaging women’s and men’s lives, race, Christianity, and American cultural history in novels simultaneously unadorned and complicated, regional and universal, and reminding us that novelists can be our public intellectuals. Panelists teased out how Robinson does what she does and what we can learn from this work, with insights for both pedagogy and our own writing.

My contribution to this panel was a presentation in the form of a craft talk on Robinson’s influential first novel, Housekeeping. In this craft talk, by isolating key aspects of the novel’s unique creative methods, I connected innovative craft points in the novel to its enduring legacy as a contemporary classic. The following essay is from my AWP craft talk on Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping.

* * *

As a writer, I have been amazed by the haunting beauty of Marilynne Robinson’s first novel, the contemporary classic, Housekeeping. The novel has been celebrated for its voice: precise, clear language expressing the inaccessible in seemingly accessible ways, elegant sentences exposing tragedy through lyricism in an internalized language of quiet characters equally ordinary and disturbing.

Housekeeping was part of my pathway as a young writer finding my voice. When I first became serious about learning my craft, I set out to read and analyze contemporary fiction that moved me and was recommended by writers I admired. Housekeeping was the novel most recommended to me as a “writerly novel”—a character-based “serious” work of literary fiction that moved its reader through voice rather than plot or action. It was also entirely female in its world, yet nevertheless complicated enough to escape the label of “chic lit” as so many contemporary novels by women writing about women were often categorized and therefore dismissed.

While reading Housekeeping, I slowed down to savor its prose but also to analyze it, to take it apart, and study it in a writerly quest to understand: How did the author write this? The world Robinson creates is realism, but not typical realism. It is a sort of cosmic realism shaped by deep interiority where a character’s lived experience is defined by inherited memory, recurring archetypal elements mapping both real landscape and the subconscious landscape of character psychology in an interiority that invites the analysis of dreams.

This analysis of dreamlike elements seems tied to interiority of the first person through a sort of implied inherited memory among generations of female characters: recurring archetypal elements mapping both the real landscape and the subconscious landscape of character psychology inviting analysis of dreams in nightmarish deaths (train wrecks, suicide) followed by dreamlike revisiting (more ghostly than ghosts in that these recurring dead return through memory as the living characters reconcile with loss). All the while, a dark lake swallows a grandfather, a mother, a town before invading the characters’ house so that Housekeeping seems to be an act of fighting the dark lake of death, evicting it from the family home, even as it continues to invade, slowly through generations in reality and dream.

As a young writer, I made notes, attempting to identify the fictional techniques that allowed Housekeeping to capture cosmic realism. I wanted to comprehend and to capture the writerly magic of Marilynne Robinson, who was retrograde in her plain language and insistence on capturing the ordinary and yet also radical.

These are the primary creative elements and craft points I noted in the novel:

- Complex female characters

- Lyrical voice

- “Realism” blended into “magic-dream” reality though character interiority

- A setting so vivid that readers feel they have lived there and long to return through re-reading as revisiting a familiar place

- Memory shaping character consciousness

- Metaphors and figurative language to illuminate and define the literal

In her use of figurative, Robinson doesn’t typically employ the standard “like/as” or “is/was” in simile or metaphor constructions. Instead, she crafts sentences that admit and invite strange, haunting, lyrical comparisons between her characters’ lived reality and the dreamlike images of their interior spiritual worlds. Just as one character’s interior life is different from others, each character exists in a different spiritual interiority, a private existence to make them whole by negotiating the loss and horror of nightmarish reality with the dignity they maintain in their visions of the unseen, private havens of faith, beliefs about lost loved ones.

Where elements of spiritual or dream life connect to a character’s reality, Robinson’s prose creates lengthy digressions in the form of figurative language, often in extended metaphors.

The novel begins with a simple sentence, generous in its accessibility: “My name is Ruth” (3). Immediately, from that first sentence, the reader knows the point of view, the first-person consciousness creating a contract with the reader who knows the protagonist. Or, as readers, do we ever really know what we think we know from the beginning? One of the most complicated, confounding, magical, and mysterious aspects of the novel is the way the narrator seems to disappear more and more after the first sentence. In the beginning, it’s easy to forget her as she tells the story of her family, going back in time to her grandmother, whose husband built the family house, was an employee of the railroad, and died by a tragic trainwreck: the train, his life, and his body swallowed by the dark lake in winter. We see the townspeople looking into the lake, boys diving into the water to try to find evidence of the lost. The catastrophe is nightmarish.

This is the story of Ruth’s grandmother, who lived her whole life in Fingerbone in the house built by her husband near the lake that swallowed him. She overcame the loss of her husband by being devoted to raising her daughters, who eventually abandoned her. Yet with all this tragedy, the grandmother is not a tragic figure. Instead, she is defined as a “religious” woman whose spiritual life rebalances reality by recovering all that has been stolen from her by tragedy. How does this happen in a realist novel? It is accomplished through the brevity and poetry of “cosmic realism” as a technique of extended metaphor. The following is a primary example of that technique and a key passage for understanding the underlying theme of the novel and its characters’ interior worlds:

It seems that my grandmother did not consider leaving. She had lived her whole life in Fingerbone. And though she never spoke of it, and no doubt seldom thought of it, she was a religious woman. That is to say that she conceived of life as a road down which one traveled, an easy enough road through a broad country, and that one’s destination was there from the very beginning, a measured distance away, standing in the ordinary light like some plain house where one went in and was greeted by respectable people and was shown to a room where everything one had ever lost or put aside was gathered together, waiting. She accepted the idea that at some time she and my grandfather would meet and take up their lives again, without the worry of money, in a milder climate.”

(9-10)

With this extended metaphor and simile combination, the narrator has disappeared into her grandmother’s story, telling of a spiritual life inside her grandmother’s consciousness, a consciousness the narrator can never really know, and through this consciousness, an imagined spiritual life of her grandmother becomes the spiritual life of the narrator as she makes sense of her family’s lives and losses by imagining a spiritual reality her family members construct for themselves.

If envisioning this spiritual realm is the key to the characterization, realism is a sort of reverse metaphoric device Robinson uses to construct a concrete image of the abstract spiritual realm, the world view beneath the narrator’s vision of the world. As the extended metaphor unfolds through Fingerbone, it’s hard to know if the heaven envisioned for the grandmother as a place of reclaimed losses is a metaphor for alternate reality or if reality is a metaphor for the spiritual future the character is journeying toward in her present.

Throughout the novel, the present absence of cosmic realism in the form of the dead and the lost is revealed, again and again, in a landscape of metaphoric interiority using figurative language to build a spiritual realm where the figurative is understood as literal. This is the novel’s innovative technique of character development through interior world building. Such is the magic of Housekeeping’s cosmic realism where figurative language helps explain the narrator’s tragic reality and the narrator’s tragic reality creates a narrative linguistic space for a figurative realm that reveals a private unknowable consciousness unveiled through a metaphorical vision of the spiritual world.

Author Bio:

Aimee Parkison, author of several books of fiction, is widely published and the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships, including: the FC2 Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize; the Kurt Vonnegut Prize from North American Review; the Starcherone Prize for Innovative Fiction; a Christopher Isherwood Fellowship, a North Carolina Arts Council Fellowship, a Writers at Work Fellowship, a Puffin Foundation Fellowship, and a William Randolph Hearst Creative Artists Fellowship. She teaches creative writing in the MFA/PhD program at Oklahoma State University. Her newest book is Suburban Death Project (Unbound Edition 2022.) More information can be found at www.aimeeparkison.com. Parkison is on Twitter @AimeeParkison.

Works Cited:

Robinson, Marilynne. Housekeeping. Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, NY, 1980.

Category: How To and Tips