Finding Time: Writing Your Book in a Busy World

Finding Time: Writing Your Book in a Busy World

by Sarah Fawn Montgomery

These days, there is never enough time. Careers, caregiving, and capitalism compete for our attention along with the latest social, political, and environmental disasters. Rest seems to be a thing of the past and writing time is hard to come by when our attention is divided.

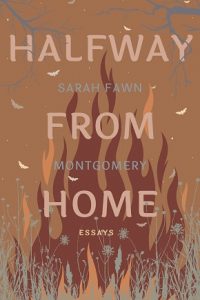

I wrote Halfway from Home—an essay collection about nostalgia and searching for home during emotional and environmental collapse—because I was struggling with time. Like so many of use, I was working full time, overtime, all the time. I was also working from the home office where I used to write, the boundaries between personal and professional vanishing along with the quiet time I used to write, all the members of my family on various Zoom calls and meetings throughout the day and well into the evening. In order to write, I had to reconceive of time entirely.

But just as limited time can be an interference to writing, it can also be an inspiration. Halfway from Home actually began as an exploration of time. I was interested in how time had changed my perception of myself and my family, my sense of place and permanence. I was interested in the human tendency towards nostalgia and the concept of time itself, like the invention of clocks and cameras, those devices we use to capture stories and record history. And I was interested in how time played a role in a world that seemed on fire—when climate change began to happen, when the environmental landscape we knew would cease to be recognizable, when it might be too late to prevent further damage.

Because I struggled to find time in my life, I turned to this topic in my writing. When work seemed to consume all my hours, I wrote about the freedom of playing by the ocean as a child back before cell phones and screen notifications. When news of the latest environmental disaster made me fear time was running out to reverse course, I wrote about the natural histories of the many places I’d called home. And when my father fell rapidly ill, his impending death making me feel as though the world was caving in, I wrote about the outdoor adventures we shared, like digging in treasure holes or watching monarch butterflies gather for warmth in eucalyptus groves each winter. Ruminating rather than agonizing about time fueled my writing.

Just as the content of my book was shaped by concepts of time, so too was my craft. As a memoirist, my previous books approached time linearly, the stories of my life scrawled and sprawled over many years of living and writing. In memoir, time had been a luxury, my books taking many years to live and many more to write. But contemporary demands on my time meant that my attention was divided, distracted even, across many topics. The story of my life no longer contained one central theme, but many themes and images, braided and woven together. This meant that the form of my book had to change entirely. By writing an essay collection instead of a more traditional memoir, I could give attention to the many topics demanding my attention these days, building a collage that more accurately described contemporary life.

Similarly, I began to rethink how I approached writing. Writing is often taught linearly. You write the introduction before the conclusion, the rising tension before the falling action. Writing advice often suggests you should write linearly towards your goal every day, for a set number of hours or until you reach a particular number of words. Today’s demands make these rules impossible for many, so the task of writing is doomed to fail before you even begin.

Instead of waiting in vain to suddenly have large swaths of uninterrupted time, I began to look for pockets of time. I didn’t have hours each day to write, but a few days a week I might have fifteen minutes in the morning and fifteen minutes in the evening. Added together over a few weeks, this was the same as a few long writing sessions. The smaller amounts of time that I began to look for, the more I found: 10 minutes waiting for a Zoom meeting to begin, 10 for dinner to simmer on the stove, 10 when I would normally be doomscrolling or watching the news announce another disaster. These pockets of time added up quickly, and soon I was writing more frequently, which made it easier and faster every time.

I also decided to reconsider what counted as writing altogether. Now writing was jotting down a few notes about California tide pools or Midwestern prairie grass while eating breakfast or brushing my teeth. Writing was thinking about tree roots or fossils while watering my plants or taking out the dog. Thinking and remembering were all part of the important work of writing memoir, yet I so often failed to “count” these towards my goals. Now talking to my parents or sister on the phone counted as writing. So did talking to my husband late at night when we were exhausted. This made me feel closer to my work rather than estranged from it. Simply living meant I was working on this book all the time rather than trying to escape my life in order to write.

The essays in this book about how to build a home when human connection is disappearing and how to live meaningfully when our sense of self is uncertain in a fractured world emerged more quickly than I expected. I didn’t focus on writing in order, instead writing a few sentences or small sections of an essay at a time and later collaging them together. The essays emerged first, comprised of the many segments I’d written in small bursts of found time. The essays collaged similarly until the book emerged. By focusing on fragments of time and writing in short spans, I created a book whose sum was greater than the many parts.

Most important, shifting my mindset around temporality allowed me to fully embrace what I could do with time reframing it as a pleasure rather than another task, a way for me to escape a world that seemed to be burning and to one that was beautiful.

Sarah Fawn Montgomery latest book is the lyric essay collection is Halfway from Home (Split/Lip Press). She is also the author of Quite Mad: An American Pharma Memoir (The Ohio State University Press) and three poetry chapbooks. She is an Assistant Professor at Bridgewater State University. You can follow her on Twitter at @SF_Montgomery

Halfway from Home

When she left a chaotic home at eighteen, Sarah Fawn Montgomery chased restlessness, claiming places on the West Coast, Midwest, and East Coast, while determined never to settle. But it is difficult to move forward when she longs for the past. Now her family is ravaged by addiction, illness, and poverty; the country is increasingly divided; and the natural worlds in which she seeks solace are under siege by wildfire, tornados, and unrelenting storms. Turning to nostalgia as a way to grieve a rapidly-changing world, Montgomery excavates the stories and scars we bury, unearthing literal and metaphorical childhood time capsules and treasures.

When she left a chaotic home at eighteen, Sarah Fawn Montgomery chased restlessness, claiming places on the West Coast, Midwest, and East Coast, while determined never to settle. But it is difficult to move forward when she longs for the past. Now her family is ravaged by addiction, illness, and poverty; the country is increasingly divided; and the natural worlds in which she seeks solace are under siege by wildfire, tornados, and unrelenting storms. Turning to nostalgia as a way to grieve a rapidly-changing world, Montgomery excavates the stories and scars we bury, unearthing literal and metaphorical childhood time capsules and treasures.

Blending lyric memoir with lamenting cultural critique, Montgomery examines contemporary longing and desire, sorrow and ache, searching for how to build a home when human connection is disappearing, and how to live meaningfully when our sense of self is uncertain in a fractured world. Taking readers from the tide pools and monarch groves of California, to the fossil beds and grass prairies of Nebraska, to the scrimshaw shops and tangled forests of Massachusetts, Montgomery holds a mirror up to America and asks us to reflect on our past before we run out of time to save our future. Halfway from Home grieves a vanishing world while offering—amidst emotional and environmental collapse—ways to discover hope, healing, and home.

—

Category: On Writing