EDITING TIPS FROM A FREELANCE EDITOR By Libby Sternberg

EDITING TIPS FROM A FREELANCE EDITOR

By Libby Sternberg

For many years, I’ve been a freelance editor at a major publishing house, editing romance novels and women’s fiction books.

For many years, I’ve been a freelance editor at a major publishing house, editing romance novels and women’s fiction books.

I started as a copy editor, checking for grammar, usage, and style, but now I’m a line—or developmental—editor, which means I check manuscripts for characterization, consistency, credibility and plot problems. Below are some of the things I’ve encountered while editing and the lessons I’ve learned from them, along with some comments from a copy editor friend who works for the same publisher:

Make your manuscript as clean as possible: If you present a manuscript to your editor thinking they’ll fix all your mistakes, the truth is…they won’t. Or at least, there’s a good chance those editors will miss a few errors if the manuscript has lots of them to begin with.

My copy-editor friend puts it this way: “The production process is speedy and at every editing step, the editor has more books waiting in line. My copy-editing deadlines are one week, whether the book is 400 pages or 150. While I try to read carefully, I must also be quick.”

When the manuscript goes back to you, the author, to review, you’ll similarly likely be on a tight deadline and be forced to accept substitutions if you can’t take the time to figure out what you’d prefer instead. The more problems in a manuscript, the more you’ll lose control of the end product as editor after editor suggests changes.

Watch out for sensitivity issues: Editors are now acutely aware of the possibility of offending, and editors at all levels read to make sure gender, racial or ethnic slurs don’t make their way unintentionally into stories. They are often subtle errors, such as using an ethnic last name for a character and giving that character unflattering stereotypical traits. In addition to these sensitivities, keep in mind that publishers have no desire to defame real people or products, so be careful with those references.

Don’t date yourself: If you’re a baby boomer like I am, it’s easy to write younger characters the way you were in your youth. Be aware of how things have changed, how reliant on cell phones younger people are, how phones are now often synced with cars, how your female characters might not wear so many pencil skirts, and how country music isn’t referred to as “country western” music anymore.

Be wary of the “replace all” function: I once edited a manuscript that had a confusing array of odd names and references in it. Finally I figured out what had happened—at some point, the author had changed the name of a character, and she must have used the “replace all” function in Microsoft Word to quickly make the changes, not checking each substitution. Because her original character name was a word that could occur in common conversation, her substitutions made for some confusing reading. Go ahead and use the “find and replace” function, but you should do the tedious work of going from change to change to make sure they all make sense.

Be wary of dictation software: “If using it, do a careful read-through,” says my copy-editor friend. “The software often omits words, the same words it’s easy to read past if reading quickly, like by, an, a, and the.”

Be wary of the TSTL characterizations: If you’re writing a mystery or thriller novel, plot can sometimes overtake characterization. When this happens, it can result in a character becoming Too Stupid to Live. They make obviously stupid decisions (going into the dark basement alone when a serial killer is in the neighborhood), in other words, that readers will have a hard time believing. Keep asking yourself: Is this credible?

Acknowledge incredible situations to readers: Sometimes you can’t avoid including incredible situations in your book, even if it does place characters in the TSTL category. If you find you must include such situations to make the plot work, at least acknowledge them to the reader with simple phrases such as “She knew it was foolhardy to head to the basement alone when the Scranton Strangler was in the area, but she felt she had no choice. She couldn’t wait…” Yes, it still strains credulity, but at least you’re letting readers know you don’t think they are stupid to think so.

When writing historical novels, don’t assume: Double-check dates of important events and historical facts. Your editors might not catch these things and, in fact, might even assume you are the expert on them.

Don’t overlook checking small details either, such as that champagne glasses were coupes, not flutes, for many years, or that men’s trousers didn’t have zip-up flies until the 1940s (and even then some men took them to tailors to have buttons replace the new zippers).

The same is true for anachronistic language. While you obviously won’t be writing a novel set in eighteenth-century England as if you were an eighteenth-century writer, certain anachronistic phrases could pull readers from your story.

“If using a contemporary phrase such as, say, ‘laid-back,’” says my copy-editing friend, “make sure your novel is set after 1969 when that phrase came into use.”

When using foreign phrases, editors will assume you know the language: Don’t assume editors will fix your foreign phrases, and don’t assume online translation software will be accurate. Check with someone who is fluent in whatever language you’re using.

When writing about town boards, don’t think Stars Hollow: As much as we all might have loved the Gilmore Girls series, their presentation of town meetings was high on fiction and low on verisimilitude. If you include such events in your book, take the time to look up how they’re usually run—how the agendas are set, the meetings “warned,” and how Robert’s Rules of Order guide what happens. You might be surprised how this could actually enhance your plot as well as keep readers who’ve served on such boards from being pulled out of the story if you get it wrong.

These are a few of the things I’ve encountered as an editor for the publishing house that employs me, but the important lesson I want to emphasize is the one I made at the outset of this essay: the cleaner your manuscript, the more you control it as it goes through the publishing process. It is a lot of work to get it as error free as possible on your own, yes, but it will ultimately be your vision in the book, and not that of a team of editors. Happy writing!

—

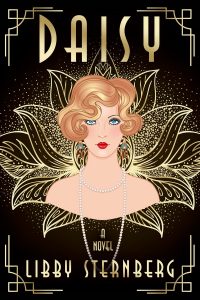

Libby Sternberg is the author of women’s fiction, historical fiction, romance and more. Her novel Daisy (Bancroft Press, September 2022), a refashioning of The Great Gatsby, has been hailed by Publishers Weekly’s BookLife: “The author writes with a poised composure that reads like a continuation of Fitzgerald’s prose…A delightful portrayal of a female character claiming the story as her own, repossessing her own voice.”

Find out more about Libby http://www.libbysternberg.com/

Follow her on Twitter @LibbysBooks

DAISY, Libby Sternberg

A fresh take on classic characters, Daisy gives readers insight into Daisy Buchanan’s viewpoint of the events of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. While simultaneously remaining true to the original and adding new information, Sternberg weaves Daisy’s perspective and Nick Carraway’s account together, correcting what Daisy knows is inaccurate from her cousin’s novel. Sternberg pulls readers in from the first page, and while the outcome of Daisy and Gatsby’s affair is universally known, readers still cannot help but root for the pair.

A fresh take on classic characters, Daisy gives readers insight into Daisy Buchanan’s viewpoint of the events of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. While simultaneously remaining true to the original and adding new information, Sternberg weaves Daisy’s perspective and Nick Carraway’s account together, correcting what Daisy knows is inaccurate from her cousin’s novel. Sternberg pulls readers in from the first page, and while the outcome of Daisy and Gatsby’s affair is universally known, readers still cannot help but root for the pair.

As the novel progresses, the tension in Daisy’s love life heightens the stakes, and while it’s easy to want to see Daisy and Jay make it work, the reader can also feel Daisy’s ambiguous feelings about leaving her husband for Gatsby. As the story climaxes, readers are left feeling as confused as Daisy is in regard to the decisions she needs to make. While there are noticeable changes to the overall story—it is a different perspective, after all—Daisy provides readers of romantic and/or feminist fiction and fans of The Great Gatsby alike with a satisfying story that is faithful to the original, yet unique in its own right.

“The thoughts and desires of Daisy Buchanan come to the fore in this well imagined novel. This is more than a retelling of the classic from a switch in point of view. The life of a pampered and beautiful yet deeply unhappy young married woman shows the dark side of the Jazz Age in a fresh and provocative telling, marked by some real surprises.” — NANCY BILYEAU, AUTHOR OF DREAMLAND

“The author writes with a poised composure that reads like a continuation of Fitzgerald’s prose… A delightful portrayal of a female character claiming the story as her own, repossessing her own voice.” — BOOKLIFE, PW-SPONSORED FICTION CONTEST, WHERE DAISY WAS A QUARTER-FINALIST

“Daisy gives needed dimensions to the controversial Great Gatsby character, turning her from a beautiful fool into a strong woman with a life of her own.” — ERIN HURLEY, LOYOLA UNIVERSITY MARYLAND —

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

“Too stupid to live!” Thanks for making me aware of the name of this familiar phenomenon. You did a nice job of laying our why it is so important to do a very thorough editing job before submission, and some of the subtle ways you can trip up. One week deadlines! Yikes! I have newfound compassion for editors!