In Praise of Meandering

In Praise of Meandering

Meandering.

It’s one of those words that’s come to have almost entirely negative connotations. From its source in the name of a winding river, Maiandros, it made its way from Greek into Latin and then the vernacular by the 16th century.

Indirect. Winding. Circuitous. Aimless.

Despite its unhappy associations, I’m here to praise meandering. Thoughtful, meaning-stuffed, memorable meandering.

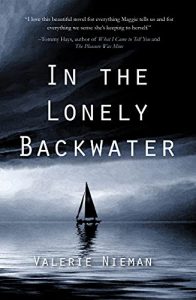

This all started with a review in the Wilmington Star-News by the estimable critic Ben Steelman. He had so many nice things to say about my most recent novel, but also noted that “Nieman is no Gillian Flynn, and “In the Lonely Backwater” is not exactly taut. The story meanders … Still, Nieman, who’s the author of “To the Bones” and “Blood Clay,” is adept at handling Southern gothic atmospherics, and the text keeps the reader going right up until the solution on virtually the last page.”

I agree. The book has been called a “page-turning thriller” by more than one reviewer, but not for the speed of incident and stripped-down prose one might expect. Instead, I was concerned with the unfolding of consciousness and conscience, ratcheting up the tension within Maggie and between her and the other characters.

Lately it seems that we as writers have been herded (with all good intentions) like rivers into concrete channels. We’ve been advised that we must hit specific beats, plan out plot points, “save the cat,” outline in detail, follow the three-act structure—all sorts of rules for channelling our fiction to the straight and narrow. While that can be useful for certain genres, for some books, it is not meant for all. Because like meandering rivers, books that breathe and are alive have space for a curve here, a riffle there, a deep pool where the big fish gather, even a swamp where story lingers to become rich and redolent of possibility. The possibility of surprise.

In the case of In the Lonely Backwater, those meanders were intentional, to both open up the text from an obsessive first-person viewpoint as Maggie wrestled with her own thoughts and threats from outside, and to enrich the story with family background and local history. A visit to a graveyard brought back difficult memories. Observations of nature led to considerations of sexuality and mortality.

Like her wanderings in the woods, this was meandering with purpose. This writer in the midst of the work finds herself akin to a flaneur wandering the city or the solitary walker on a poet’s path, not trying to cover ground or maintain steady speed, but to adapt to the day, the place, the emotional color.

Let’s go back to that river, that winding river that throws out meanders left and right as it finds its way across the landscape.

A natural stream will be shaped by the land and will shape it in turn, undercutting banks and making oxbows as it creates its path. It bears no similarity to the arrow-straight concrete-lined ditches that shoot water from one place to another like a fire hose. The march of American progress meant that rivers were “tamed” from coast to coast and especially in the American West, where the hydrology was so upended that our industriousness has desiccated enormous lakes, emptied the Colorado, and turned rivers in Los Angeles and elsewhere into ditches that become flash flood deathtraps. Recent events, with drought followed by flood, have shown the long-term folly of short-term gain.

While people ponder the return of Tulare Lake where acres of almonds once grew, elsewhere rivers are being restored in order for them to nourish the land again. Dams have been taken down in the Northeast and Northwest, allowing fish to spawn in ancestral waters. The National Geographic recently published this story about Florida’s waterways: “Sixty years ago, the Kissimmee meandered for more than 100 miles from the Kissimmee Chain of Lakes to Lake Okeechobee, and its floodplains were home to seasonal wetlands rich with life.” But following floods and hurricanes, the Army Corps of Engineers began work in the 1960s to turn “the meandering Kissimmee into a 30-foot-deep, channelized canal. Within a few years, populations of waterfowl dropped by 90 percent, bald eagle numbers by 70 percent, and some fish, bird, and mammal species vanished.”

It hasn’t been easy to turn around the ship, but state and federal and local governments and nonprofits have been laboring to restore what was destroyed, with great success. The Kissimmee River again meanders. Life is returning.

As Siddhartha was advised by the ferryman: “The river has taught me to listen, from it you will learn it as well. It knows everything, the river, everything can be learned from it.” As writers, we have to seek the voice of our internal river and trust its course, including the meanders.

The balance between plot movement and character development, between a fully realized setting and one more minimalist, description versus action, dialog that sets the pace—writers are testing those elements in every paragraph, every chapter. The answer is never the same. The landscape changes. The impetus moves the story now fast, now slow. The story develops in an organic fashion.

I’ll finish with this bit of familiar wisdom from J.R.R. Tolkien: “Not all those who wander are lost.”

—

Valerie Nieman is the author of In the Lonely Backwater, winner of the 2022 Sir Walter Raleigh Award, and four other novels as well as books of poetry. Her next novel, Alba, will be published in 2025 by Regal House.

IN THE LONELY BACKWATER

All seventeen-year-old Maggie Warshauer wants is to leave her stifled life in Filliyaw Creek behind and head to college. An outsider at school and uncertain of her own sexual identity, Maggie longs to start again somewhere new. Inspired by a long-dead biologist’s journals, scientific-minded Maggie spends her days sailing, exploring, and categorizing life around her. But when her beautiful cousin Charisse disappears on prom night and is found dead at the marina where Maggie lives, Maggie’s plans begin to unravel. A mysterious stranger begins stalking her and a local detective on the case leaves her struggling to hold on to her secrets—her father’s alcoholism, her mother’s abandonment, a boyfriend who may or may not exist, and her own actions on prom night. As the detective gets closer to finding the truth, and Maggie’s stalker is closing in, she is forced to comes to terms with the one person who might hold the answers—herself.

All seventeen-year-old Maggie Warshauer wants is to leave her stifled life in Filliyaw Creek behind and head to college. An outsider at school and uncertain of her own sexual identity, Maggie longs to start again somewhere new. Inspired by a long-dead biologist’s journals, scientific-minded Maggie spends her days sailing, exploring, and categorizing life around her. But when her beautiful cousin Charisse disappears on prom night and is found dead at the marina where Maggie lives, Maggie’s plans begin to unravel. A mysterious stranger begins stalking her and a local detective on the case leaves her struggling to hold on to her secrets—her father’s alcoholism, her mother’s abandonment, a boyfriend who may or may not exist, and her own actions on prom night. As the detective gets closer to finding the truth, and Maggie’s stalker is closing in, she is forced to comes to terms with the one person who might hold the answers—herself.

BUY HERE Regal House/Fitzroy Books and https://bookshop.org/

Category: On Writing