First Kisses, Real and Imagined

First Kisses, Real and Imagined

by Karin Cecile Davidson

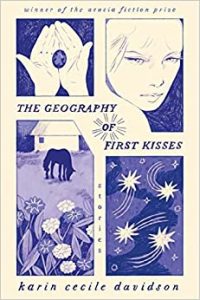

In the past few months, my story collection The Geography of First Kisses has allowed a way in for prospective readers to speak of their own first kisses. A First Lady’s first kiss as a young girl under a front porch light. An elderly gentleman’s remembrance of full lips under a full moon. A girl’s memory of butterfly kisses from when she was much younger with her grandmother, their eyelashes fluttering together, and her grandmother laughing and saying,“Honestly? The first one? No idea,” her voice trailing behind her, the memory gone. And while these stories are lovely and spontaneous, it’s the first kisses in literature, rather than in real life, that draw me in.

I’ve been reading Middlemarch, and George Eliot’s take on first kisses has me laughing aloud at times. Between all the “pray tells” and bowed heads and hand kissing, there are also brow kisses (Mr. Casaubon upon Dorothea) and metaphorical kisses (Dorothea upon Mr. Casaubon’s “unfashionable shoe-ties”). And then immediately following these unromantic pathways toward actual first kisses, the rush into marriage. As Eliot writes, “Why not?” Of course, the fact that one must wait until Book Eight, “Sunset and Sunrise,” for the long-awaited moment between Dorothea and Will is an extreme act of willing patience on the reader’s part. Worth it? I’d say absolutely, especially given all the tension that’s built within the waiting and the ultimate crescendo created by stormy weather, from heavy skies and shivering trees to “rain … dashing … the windowpanes” to trembling lips. Even the heavens become involved.

Reaching beyond Eliot’s novel, one might consider Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, wherein lips and hands, palm to palm, lead to prayers and finally purged sins inside first kisses. Whereas, in J.M. Barries’s Peter Pan, Wendy promises Peter a kiss, of which he has no knowledge and continues not to understand when instead she gives him a thimble. While this is no first kiss, its symbolism is sweet and enchanting and continues to be one of my favorites. There are practiced kisses between children in Jeffrey Eugenides’s Middlesex, the threat of unknowable kisses in Diannely Antigua’s poem “Some Notes on Music” and throughout her collection Ugly Music, the rating of kisses in William Goldman’s The Princess Bride, the fact of Wesley and Buttercup’s kiss canceling all kisses before and after theirs, and the pulse and tremble of Mathilde and Lotto’s kisses turned lovemaking in Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies. Jay Gatsby’s demure kiss upon Daisy Buchanan’s cheek in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby remains worlds away from the predatory nature of Humbert Humbert’s initial intimacy with underaged Lolita in Nabokov’s novel, while the illusion of innocence drifts among the passages of both books.

The idea of innocence leads back to where I began and straight into the title story of The Geography of First Kisses, in which the reality of wishing for that first romantic kiss, before becoming “sweet sixteen and never been,” turns a hard corner into places darker and more brutal than the unnamed narrator ever imagined. And yet she follows this path, testing its topography, leaning into spaces where “glances” led to kisses and then “roaming hands” and eventual backseat bondage. Granted, these are strange places to travel within the first two pages, though, quite unlike Wendy’s thimble for Peter, perhaps more like Lolita’s wild rush toward adulthood, and worlds away from that metaphorical Middlemarch shoe-kiss, there are so many ways to approach and linger in the first instances of love. Parents’ first kisses on beloved babies, the peck and preening and courtship among teenagers, the trust of children in adults when bestowed with bedtime kisses, wished-for kisses between strangers, kisses that lead to boredom or babies or abuse, sudden kisses that seem to come out of nowhere, and the lingering adoration of couples who have weathered years together. These universal moments of love are everchanging and yet consistent, as in the crossover from pale morning to darkening night’s first stars and back again, the sun rising, promising, the sunset and sunrise of Eliot’s eighth book weighing in again, the longing to belong revealed, from love found and lost ways to first kisses and even last words.

Karin Cecile Davidson is the author of the story collection The Geography of First Kisses, winner of the Acacia Fiction Prize, and the novel Sybelia Drive. Her stories have appeared in Five Points, Story, The Massachusetts Review, Colorado Review, and elsewhere. Her awards include an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award, the Waasmode Prize, the Orlando Prize, and residencies at the Fine Arts Work Center, Atlantic Center for the Arts, and The Studios of Key West. Originally from New Orleans, she now lives in Columbus, Ohio. Her writing can be found at karinceciledavidson.com.

Karin Cecile Davidson is the author of the story collection The Geography of First Kisses, winner of the Acacia Fiction Prize, and the novel Sybelia Drive. Her stories have appeared in Five Points, Story, The Massachusetts Review, Colorado Review, and elsewhere. Her awards include an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award, the Waasmode Prize, the Orlando Prize, and residencies at the Fine Arts Work Center, Atlantic Center for the Arts, and The Studios of Key West. Originally from New Orleans, she now lives in Columbus, Ohio. Her writing can be found at karinceciledavidson.com.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF FIRST KISSES, Karin Cecile Davidson

In The Geography of First Kisses, one finds portrayals of quiet elegance reminiscent of early-20th-century art films. The fourteen ethereal stories are tethered to the bays and backwaters of southern Louisiana, the fields of Iowa and Oklahoma, the pine woods of Florida, places where girls and women seek love and belonging, and instead discover relationships as complicated, bewildering, even sorrowful.

In The Geography of First Kisses, one finds portrayals of quiet elegance reminiscent of early-20th-century art films. The fourteen ethereal stories are tethered to the bays and backwaters of southern Louisiana, the fields of Iowa and Oklahoma, the pine woods of Florida, places where girls and women seek love and belonging, and instead discover relationships as complicated, bewildering, even sorrowful.

A New Orleans girl spends a year collecting boyfriends and all the while considers the reach of her misadventures; a newlywed couple travels to Tulsa in search of a horse gone missing, perhaps more in search of themselves; a new mother is faced with understanding the miracles and mysteries of faith when her baby disappears; a young daughter travels to Tallahassee with her mother, trying to unravel the meaning of love crossed with abandonment. Saturated with poetic illusion and powered with prose of a dark, pulsating circuitry, the collection combines joy, heartache, and tenacity in a manner sorely missed in today’s super-structured literature.

“The Geography of First Kisses maps a lush world of love, loss, and memory. Prismatic and crystalline, Davidson’s prose dazzles.” —C. Morgan Babst, author of The Floating World

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing