A Daring Performance: Caitlin Hicks

Caitlin Hicks is an international playwright, acclaimed performer and prize-winning author in British Columbia, Canada. In this piece, she shares what happened when she performed her play SIX PALM TREES in front of her family.

Everyone was there including my mother’s sister, Aunt Cecile, who hadn’t died yet. All my siblings and a number of the 42 grandchildren who had been born by that time were all seated on folding chairs in the lanai. It was a warm, hazy California afternoon

Everyone was there including my mother’s sister, Aunt Cecile, who hadn’t died yet. All my siblings and a number of the 42 grandchildren who had been born by that time were all seated on folding chairs in the lanai. It was a warm, hazy California afternoon

I still have the pictures. I’m wearing a white jacket and my hair (tied up in six ‘palm trees’) is stuffed under a bright pink cap, backwards on my head. A jock strap fits over my left breast like one half of a bra, and when I look at that picture now, it reminds me that the jockstrap joke worked every time.

The best part was, their laughter. There I was, in front of my enormous family, and every single one of them was paying full attention to me. At last, I had their total focus, and the things I was saying were making them hoot and howl with delight. In comedy lingo, I was killing.

All the longing to be with them, to be part of them again, melted in those moments, in spite of the fact that I had betrayed them all by falling in love with an ex-Catholic Canadian artist, turning my back on God and my country.

They had grown up to be doctors and lawyers and insurance salesmen, grocery store clerks and bankers, housewives, nurses and teachers: proud Yanks who still went to Sunday Mass and baptized their children; but in this moment I was a rogue, living my life as a solo actress/playwright in Canada — — and they were eating out of my hand.

The room was brimming with happiness, but we were fast going into the dip. I knew it was coming, because I had toured the play internationally to standing ovations for the past five years. It suddenly gets up close, personal and very serious. Blasphemous, some might say, in this context. I mocked their fear of Communism with memories we all shared; skewered the seriousness of Catholic with a jock strap and fart jokes.

Then I made them cry.

My Canadian husband Gord Halloran and I had written Six Palm Trees together; he directed. The ruse of the play: we were at a family reunion and Annie Shea was the stand-up entertainment. What we loved: our combined humor, my timing, the silly bits — worked on the audience every time. The laughter opened them up, got them to relax. And then we hammered them with the poignant moments where I said the ‘vagina line’, got angry with the Dad for having too much Catholic sex and cried real tears for our Mother who was dead and gone. Sometimes audiences were so stunned by this that they would stare with their mouths open in total silence when the curtain went up, just before they leapt to their feet.

But as my family gathered to finally see this play I remember thinking would they get it?

And Six Palm Trees: It’s not the real story, it’s fiction, with mixed up names and super exaggerated scenarios. The similarities – our Mother was dead, it was a family of fourteen, we did live in Pasadena — that was the outline, painted in broad strokes. Gord came from a Catholic family of seven from Belleville, Ontario, Canada and his family loved it – all the while assuming we were talking about them and them alone! And, in most of Gord’s post-show notes, as director, he’d told me again and again that the arc of the story would sing if I could ‘get really mad at The Dad’ – something that as an actress, I could never quite manage. I wasn’t mad at my father for how he treated our mother; I had no knowledge of their sex lives, nor wanted to; but the whole thing seemed so sad to me – she was the first to give us life, and the first to die. And now she was forever missing. Surely the toll on her body of creating fourteen babies from scratch – surely that helped weaken her towards her demise. At the time I didn’t really know that Mother was the one in their relationship who insisted on adhering to the Catholic restrictions on birth control.

Right then, just before performing this seasoned play in front of my actual family, I was seriously tempted to edit. What should we do? I whispered to Gord as we set up the makeshift stage in front of a door. I was thinking with panic: How could we tell this story to these people, who as far as I know haven’t gone to see a piece of theatre since the high school drama production “Of Poems, Youth & Spring”. Decades ago.

All these people, who I’m guessing, don’t understand how creating a piece of art is a cultural exploration of something that’s not fully worked out – you explore it through the creating and presenting of the work. And – you have to push the envelope, so your audience will think deeply about your subject matter. In theatre, it’s all about drama.

But, if I did edit out the vagina line, the Catholic hands outburst, the accusation, how would it end? What would it even be about? This work has held up because it asks questions about all our mothers, how we use their bodies to come into the world, how our relationship is defined by what they do for us.

I want you to know that regardless of anything my father may have done for his own benefit at the expense of my Mother, that in spite of the Fifties & Sixties in which we were raised, regardless that the expected roles of men and women went hand in hand with male privilege in Catholicism, regardless of all the abusing and hiding behind the patriarchy of the Bible, the prayers, the songs, the hymns and sermons, every reminder every day repeated over and over, so we won’t forget who is at the service of whom, regardless of all that-my father really loved my mother and truly missed her every day she was gone out of his life.

And I’m a committed performer. I open my heart and let it speak to me onstage.

So I know it was painful for him to hear my questions, beginning with, “How did she feel about each one of us when she first met us?” It was painful for all of us to hear me talk about her legs, ribboned with varicose veins, her hands, chapped and cracking from wringing out diapers into the toilet. Her abdomen, scarred by stretch marks. The absence of her. These were the shocking moments leading up to ‘getting mad at the Dad’. He was in the back row, and before I even got to the vagina line, he shuffled out of the room. I carried on; my family was as still as I have ever experienced an audience to be. Annie spoke through tears after having said what I had dared to say out loud. She tried to make amends spreading the blame across the entire family, like she does every time I inhabit this fantasy. She took back the dramatic anger at the Dad with: “She gave all of us her life – and we took it.”

After the bow, the little kids rushed up to me laughing and re-living the fart jokes. My sister said, “We weren’t that poor”; a sister-in-law asked me about a family secret. She didn’t know it yet, but one of my brothers had fathered a child ‘out of wedlock’, whose name was never spoken. And after opening up as Annie Shea in my performance I thought: she’s our niece, she’s part of this family, why can’t we speak her name? And I told my sister-in-law that her husband had a child living in the world. Who was ours, but about whom, we couldn’t speak.

The next day around the breakfast table, both Gord and I tried to explain the bit about art, drama theatre. Nobody got it.

Many years later, home after my father’s funeral, still high with a strange euphoria of love and connection with my family of origin; I opened a FEDEX package from the lawyer in California. And when I read the words that my father had disinherited me, I was not really, really super surprised. By then I understood the moment on the lanai when I dared to finish the play I had written with my soul mate. I had chosen to live apart, to speak the voice of my freedom, the voice of my maturity.

Giving voice to my work, I had told them:

This writer, this performer, this woman who lives in Canada, this is who I am.

—

Caitlin Hicks is the author of the 2015 novel A Theory of Expanded Love, which won many awards, including IndieFAB Bronze (now Foreword Indies) and iTunes for “Best New Fiction.” In 2022, the novel won listing on BookRiot’s list of 100 must-read books about Women and Religion alongside celebrated writers Alice Walker, Barbara Kingsolver, Toni Morrison, Arundhati Roy, Margaret Atwood, Ann Patchett, Alice Hoffman and more.

The audiobook of A Theory of Expanded Love won NYC BIG BOOK AWARD as a Distinguished Favorite in 2022.Hicks is also an international playwright and acclaimed performer. Her theatrical writing has been performed in Best Women’s Stage Monologues (New York), SheSpeaks (Playwrights Canada Press), and Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s national radio.

A screen adaptation of Hicks’s internationally toured play Singing the Bones debuted as a feature film at Montreal World Film Festival (2001) and screened around the world. Hicks’s writing has been published in Vancouver Sun, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, The Fiddlehead, and other publications. Her podcast SOME KINDA WOMAN, Stories of Us, captures women’s voices at small and profound moments in their lives.

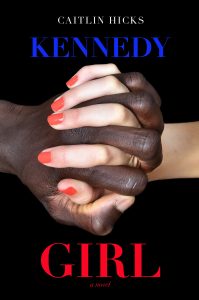

Kennedy Girl, the follow up of A Theory of Expanded Love is out now.

Learn more at CaitlinHicks.com

KENNEDY GIRL

An uncontrollable series of events transform the lives of two teenagers the night of RFK’s assassination. The unforgettable heroine of A Theory of Expanded Love returns in this coming-of-age adventure about love, justice and the memorable year of 1968.

An uncontrollable series of events transform the lives of two teenagers the night of RFK’s assassination. The unforgettable heroine of A Theory of Expanded Love returns in this coming-of-age adventure about love, justice and the memorable year of 1968.

Seventeen-year-old Annie Shea is feeling good about her life. Performing a solo in a glee club production of HAIR, she has a crush on the show’s star, Lucas Jones, a talented black singer/dancer from Watts. Annie sneaks away from home to volunteer for Robert Kennedy, and proudly rides alongside his car as part of his campaign entourage.

On a hot June night inside the crowded ballroom of The Ambassador Hotel, Annie and Lucas witness the triumph of RFK’s presidential campaign. Seconds later, RFK is shot, and the two follow his ambulance through the streets of LA—a tragic and chaotic ride that upends their young lives forever.

Soon after, Annie ditches her first day of university to drive Lucas and her brother to Canada to evade the law. Throughout the suspense of their hasty road trip up the coast of California, Annie unearths her brother’s unbearable secrets. She connects with Lucas’s generous heart while sorting out justice and privilege, racism, sexuality, love, and the dark forces of war.

In the sequel to the award-winning A Theory of Expanded Love, Annie is determined to find her voice. Thrust into making excruciating decisions, Annie begins to understand the new roles she must navigate as a woman in a fast-changing society, amidst the chaos, danger and social change of the late Sixties.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing