Happy Landings: Emilie Loring’s Life, Writing, and Wisdom: Review

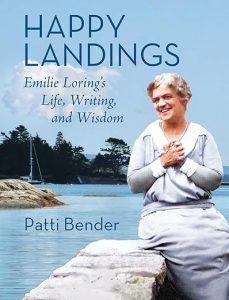

Happy Landings: Emilie Loring’s Life, Writing, and Wisdom

City Points Press, 2023

Review by Martha Wolfe

How does an author, one whose thirty novels sold over five-million copies and were translated into nine languages, whose name appeared on best-seller lists alongside Pearl S. Buck, Sinclair Lewis, Faith Baldwin, and Agatha Christie, one to whom new authors were compared and who was nominated for a Pulitzer, fall into obscurity?

How does an author, one whose thirty novels sold over five-million copies and were translated into nine languages, whose name appeared on best-seller lists alongside Pearl S. Buck, Sinclair Lewis, Faith Baldwin, and Agatha Christie, one to whom new authors were compared and who was nominated for a Pulitzer, fall into obscurity?

Dr. Patti Bender introduces us to just such an author in a new literary biography, Happy Landings: Emilie Loring’s Life, Writing, and Wisdom. Though we may have never heard of Emilie Loring, millions once read her novels. Loring rejected the term used to describe her chosen genre, “romantic,” for another: “optimistic.” Her obscurity among dismissive literary circles may be due to the former; her longevity among others speaks to the latter. In Bender’s words, Emilie Loring’s books were, “like a cardigan sweater—classic, comfortable, never too much or too little.”

Loring’s life and work fed Patti Bender’s boundless curiosity—about writers, about women’s lives in the first wave of American feminism, about twentieth-century history and politics. Bender’s Ph.D. is in human motor control and learning. Her academic career has focused on kinesiology and designing spaces to support creativity. Her mantra: “Everything you learn allows you to see more.” Her biography of Emilie Loring helps us see more of a subject worth learning about.

Born in the shadow of the Civil War, Emilie Loring (1866-1951) witnessed two presidential assassinations, a world-wide epidemic, the Great Depression, and two World Wars during her lifetime. She came from a bookish family of publishers, comedic actors, and playwrights. Her grandfather published a penny newspaper that became the Boston Herald. Her father was an amateur dramatist whose play, “Among the Breakers” is the best-selling amateur drama of all time. Emilie Loring began her writing life early in 1911 as a book reviewer, publishing her first short story two years later, and her first novel in 1922 at the age of fifty-six.

A book a year for thirty years speaks to her work ethic. She set a daily writing schedule and stuck with it. Rejection was not a part of her lexicon. She revised and resubmitted her short stories and novels over and over until they were accepted. William Penn Publishing Company published her first fifteen, Little, Brown and Company the remainder.

Her writing was steeped in an aristocratic Bostonian tradition, published for and read by women for whom suffrage was still a question mark. Loring’s husband, Victor, was a successful Cambridge attorney and they lived in Wellesley, a Boston suburb. For Emilie, success took on a different meaning. The women’s clubs and the lunches and teas that she hosted in her own home sparked her imagination. She found friends with whom she could discuss writing ideas, all the while learning that, “talking of ideas doesn’t get one anywhere. No matter how brilliant or useful they may be, until they are formulated on paper they don’t count as creative writing. There is a little word of four letters W O R K which does the trick.”

In January, 1922, the Boston Authors Club heard Helen Sard Hughes of Bryn Mawr College speak about the current state of literature in America. “The virgins of earlier centuries,” professor Hughes expounded, “preferred the literature of delight to the literature of education,” comparing romance novelists to the Roaring Twenties’ flappers. Loring and two of her Boston Authors’ Club friends, who also preferred to delight their readers with a little romance, generally sat in the front row at meetings. They collectively thumbed their noses at this critic who valued grimness over optimism, dubbed themselves “Flapper’s Row,” and went on with their work. Gaining access to the Boston Athenaeum through a friend of her husband’s, Loring and two writing friends found a quiet alcove of their own. From there, in the heart of traditional Boston, Loring sat down each day “with her emerging draft, fresh paper, and two-dozen, sharpened pencils.”

Post-war reaction to “sunny” stories made a rift in publishing. Loring’s The Trail of Conflict came out the same year as Hesse’s Siddhartha and Eliot’s The Wasteland. In Patti Bender’s words, Emilie’s attitude, “was less a matter of avoiding the negative and more that she was committed to the positive.” Penn produced a promotional flyer for their line of “Novels of Romance and Adventure,” in which Loring was quoted: “I am neither a super-optimist nor a Pollyanna, but behind the thickest cloud, behind the darkest situation, somehow, I sense the sun ready to break through. Why not? It always has.”

When the markets crashed in the fall of ’29, Emilie Loring survived. By 1932 The Boston Globe was comparing her work to that of Thackeray, DuMaurier, and Barre, placing her on the Depression era’s list of best-selling authors. “Happy Landings,” adopted from a congratulatory letter to Charles Lindbergh on the first anniversary of his trans-Atlantic flight, became her catch-phrase. She was featured on nationally syndicated radio WEEI and in 1936 Charles Shoemaker nominated her for a Pulitzer. Alas, that year’s prize for fiction went to Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind.

Happy Landings is a comprehensive literary biography covering Emilie Loring’s life and work. Bender’s joyful writing style, reinforced by far-reaching historic and genealogical research, brings Emilie Loring’s life to us with telescopic focus. From cover, to photographs, to illustrative sidebars, this book dives into the life and work of a once, if not great, damn good twentieth-century American author.

You can find Patti Bender’s work at https://pattibender.com/

–Martha Wolfe earned her MFA in creative writing and literature from Bennington College. She is the author of “The Great Hound Match of 1905; Alexander Henry Higginson, Harry Worcester Smith and the Rise of Fox Hunting in Virginia” (Lyons Press, 2015). Her essay “The Reluctant Sexton” won honorable mention in the Bellevue Literary Review’s 2018 annual contest. She lives with her husband, her dog Luke, a couple of horses, some sheep, some donkeys, a few chickens, and a guinea hen in Virginia. She is working on Mary Lee Settle’s literary biography under contract with West Virginia University Press.

Category: On Writing