Writing Amoral Characters

Being in the teaching profession is a wonderful gift.

Teachers meet a variety of students as they grow intellectually, take academic leaps, and learn to think critically. Teachers constantly learn from their students, and reflect on the variety of personalities, beliefs, and outlooks of these young adults who will shape the world of tomorrow.

Teaching literature raises issues about what being human means.

In a literature class, we read about the human spirit in its best and worst light. And we think about how we react and relate to what we read. Our emotional reactions become a barometer of our outlook of the world, our view of people, and those things we think are the most important in life.

Several years ago, we were discussing a Shakespeare play and talking about certain characters’ views of the world. This inevitably led to a comparison with our own beliefs.

- Did we think the world was good?

- Did we believe in a higher force, and if so, what were our beliefs?

- Did we believe in our capacity to choose? To shape our own future?

One student’s response still rings in my head all these years later:

“I believe in genetics. Genetics and statistics.”

Please explain what you mean.

“Everything you do is pretedermined by your genes. Whatever isn’t becomes a matter of statistics.”

Whoa. Had I actually heard that from one of my smartest students? I had. I reminded myself that this was a science major,

someone whose thinking was decidedly not like mine, although his point of view was certainly just as valid. In fact, his comment sparked a lively discussion related to fate and free will, both in our lives and in the play.

Long after I forgot the student’s name, I remembered his remark, as well as the questions I asked myself in its aftermath. Questions such as:

- What would the world look like to you, if you didn’t believe in something bigger, something better, than yourself?

- What kind of life shapes the outlook that everything in the world can be explained through science and/or chance?

- What kinds of things would you strive for?

- Would the idea of ethical behavior make any sense from a strictly scientific point of view?

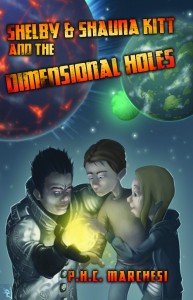

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with my writing, here it is: Dale Falconbridge, one of the characters in Shelby and Shauna Kitt and the Dimensional Holes, was inspired by that student’s remark.

Dale is an amoral character. Merriam Webster Dictionary Online lists this meaning “Being neither moral nor immoral; specifically: lying outside the sphere to which moral judgments apply <science as such is completely amoral— W. S. Thompson>.” My goal was to create someone whose motivation was different from other teenagers’, someone for whom moral judgments were meaningless. I wanted to explore the causes of such behavior, as well as its consequence in the real world. I wanted to answer the very questions I had been asking myself since that student shocked the class with his matter-of-fact observation.

In the novel, Dale is forced to experience a different perspective when he meets Shauna Kitt, with whom he becomes fixated. Here is an excerpt that showcases their contrasting views:

[. . .]

“I can go with you to the dining hall,” offered Dale. “I think the staff is still in the kitchen.”

Shauna hesitated. She was starving, but she wasn’t sure she wanted to go anywhere with Dale.

“Can you stay here with Shelby?” she asked Ian, who was sitting next to Shelby’s bed, completely absorbed in reading an old magazine he had found.

“Sure,” he said. “I’m not going anywhere.”

Shauna nearly regretted her decision to go with Dale when she saw that the hallway was empty. She didn’t like the idea of walking alone with him, especially if there was a chance he could be the spy – or worse. But she had already said yes, and it would look weird to change her mind. Besides, she was too hungry to turn back now – the grumbling in her stomach spoke more loudly than anything else.

“I heard Shelby broke his ankle,” Dale said, shattering her hopes of a conversation-free walk to the dining hall. “It didn’t look broken.”

“Lendox put some stitching spiders in there,” she said. “He said Shelby won’t even feel his ankle until they come out again.”

“I wish we had bugs like that here on Earth,” he said.

“Why? So you’d stick them under your microscope?”

Shauna froze. She shouldn’t have said that. Now Dale would know for sure that she had sneaked into his room.

“Don’t worry,” he said, mechanically. “I already knew it was you.”

“Why didn’t you tell your dad?”

“I didn’t want to,” said Dale. “He doesn’t get me.”

“I don’t get you, either,” said Shauna. “If you’re so smart, why do you need to mess around with bugs and mice and stuff like that?”

“I’m bored. There’s nothing interesting to study here.”

“Here at the base?”

“Here on Earth. I already know everything – everything that human science has to offer, in any case.”

Something about the casual boredom of Dale’s tone frightened Shauna – especially as she felt, almost against her will, that he was speaking the truth. But how could he be? No one knew everything – not even Lendox. Maybe if she didn’t say anything, Dale would change the topic, or stop talking altogether.

“We’re so limited here, anyway,” he continued, much to her disappointment. “If I could, I’d go to space. Can you imagine how much new stuff there’d be to learn in an infinite universe?”

“You wouldn’t be able to learn everything, though,” she said.

“That’s the point,” said Dale. “I wouldn’t get bored. It’s awful to know everything.”

Shauna couldn’t quite explain why, but she found herself feeling sorry for Dale.

“I don’t think you know everything,” she said, simply. “I mean, maybe you know a ton of facts and stuff, but that’s not everything.”

“What do you mean?” he asked, and though his voice had the same monotone sound, his eyes were less watery than usual.

“Well, there’s stuff like feelings,” said Shauna. “If you knew anything about feelings, you wouldn’t keep all those glass jars, because you’d feel sorry for the bugs and mice and frogs you kept in there.”

“Compassion,” said Dale, as if he had managed to find a matching word to what Shauna was describing. “I see.”

“It’s not just a word in a dictionary,” said Shauna, shocked by his indifferent tone. “How would you feel if someone took you away, put you under a microscope, and did all sorts of horrible things to you?”

“I suppose I would want them to stop,” he said, after a pause.

“There you go,” said Shauna. “And what would you want to do if you got the chance?”

“I’d escape, and be free, and make sure no one ever harmed me again.”

“Well, that’s exactly what they want,” said Shauna. “Get it? You’re not that different.” (Chapter 11, “Spiders and Space Ghosts”)

Writing the character of Dale Falconbridge was a challenge, because he is so unlike myself. Still, I would be lying if I didn’t say it was one of the most interesting things I’ve ever done. In the end, I learned quite a bit about myself as I resisted and then finally allowed Dale to be himself, to have a life of his own independent of my own feelings and values. I now find he is one of the most interesting characters of the novel, and one who will continue to develop in the sequel to Shelby and Shauna Kitt and the Dimensional Holes.

—-

Leave a comment for PHC, let her know what you found interesting and what you think.

Follow PHC Marchesi on Twitter @PHCMarchesi, and Like her book’s Facebook Page. Order a copy for someone you know. Subscribe to PHC Marchesi’s Blog.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, Women Writing Fiction

Interesting, this challenge of creative characters we’d cross the street to avoid. I try to think about their childhoods, where this lack of empathy comes from – then their behaviour makes more sense, and may make it easier to live with them for as long as it takes you to write the book. And few people are all bad or all good – most are a mixture. So even the baddie needs the occasional redeeming features.

Nice article! It’s remarkable how just one real life or imagined comment can spur an entire character, or even novel, into being. In my experience with character-shaping, I know I’ve had issues with writing the ones who are actually good people, but are behaving badly or irrationally. In my eagerness to have the situation resolved, sometimes I do not allow the scpace for the character to have those moments, which eventually allow them to grow. These days I’m better at recognizing that, catching it, and being able to say, “that’s me getting in there, instead of the character. I need to back off to let them come to their own resolutions.” It’s not only not fair, but also horribly stifling for me to deprive them of their moments–good or bad.

I find it so hard to write characters who have a completely different worldview. I find myself changing them too soon, I make them too malleable. It’s definitely something to work on. Thanks for putting it in a way that I could take on board 🙂

Great article! Just bought my copy on Kindle!