Clichés – drag or opportunity?

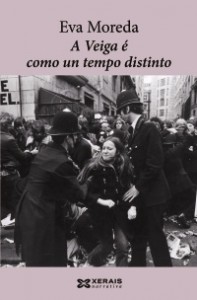

Eva Moreda (picture by Xenia Blanco)

In my Twitter profile, I define myself as an ‘enemy of set phrases and cliches.’ Nothing makes me feel like putting down a novel like two, three, four, five cliches strung together without any self-awareness, any twist or turn, not even the faintest attempt at turning into something mildly interesting – what kind of original thinking, of engaging, can happen when we look at language and the world exclusively through clichés?

And yet, I am aware that literary communication can only happen when there’s some shared experience between a writer and her readers. When I recently read The Beet Queen – my introduction to Louise Erdrich -, there was certainly an air of familiarity throughout: even as a non-American, I have been sufficiently exposed to the cliché of the God-forsaken Midwest rural village sleepily drifting through the Great Depression, the war years, the explosion of consumerism and the middle class in the 1950s.

I confess to having thought “No, not again” a couple of times as I stumbled across clichés I knew from my literary and filmic story, but, paradoxically, I think it was this familiarity which made it for me, allowing me to take the plot, the setting and the characters for granted to a certain extent and focus instead on Erdrich’s powerful, difficult-to-take-for-granted style.

Certainly, all writers, including the great ones, use clichés. After all, complete originality is impossible and may not even be desirable. Greek, Roman and medieval writers were only too aware of it – back then, notions such as originality, innovation and individual authorship did not have the meaning they do now, and clichés, under the name of topoi, were made into a system, a repertoire for writers.

There was, for example, the ‘ubi sunt’ topos; ‘ubi sunt’ means ‘where are they’, and thus the writer would ask where were now the people, objects or landscapes he knew from his youth. It was not so much about finding something new and original to say; there aren’t, after all, that many big themes to write about, and I’m sure that the passage of time (which is what ‘ubi sunt’ is about) has preoccupied most human beings. It was rather about filling the ‘ubi sunt’ topos with meaning, to make it relevant to one’s readers, to make it come alive.

But how exactly do you go about that? I am afraid I do not have a proper recipe, but rather a couple of examples from recent readings. The secret, I think, is not to avoid the cliché at all costs, or turn it over its head in an artificial way, but rather to fill the cliché with something else – humanity, emotion, one’s very personal style – so as not to make it all about the cliché.

In the last few months, I have been reading quite a lot of Benito Pérez Galdós, typically considered the great figure of Spanish realism, who has been accompanying me on many a fruitful plane, bus and train journey. And yet when I try to explain to others why is it that I like Galdós, I fail miserably.

As I tell the plot of his novels, I realize that most of them are nothing but a collection of nineteenth-century serialised novel clichés: children born out of wedlock, lost women locked in convents, infidelities, impoverished aristocrats. But when I’m reading his novels, I don’t feel as if these are clichés. The characters are so powerful, so masterfully constructed and so full of humanity, that all what happens to them interests me, moves me, touches me. I don’t care if what happens to them has been told ad nauseam by hundreds of realist novelists before – I care about these characters.

Set phrases can be regarded as a particular variety of cliché. Here we may want to make a distinction between the narrative voice and the characters’ voices – of course, a character’s constant use of set phrases can crucially help in defining him.

But what if the narrator is a character? Doesn’t it become too tiresome to be using clichés all the time? How to make the distinction between a character who, because of her background, understands the world to a great extent through clichés and set phrases and the author, who knows (or should) know better – how to make the reader aware of both?

One of my favourite examples comes from the Galician novel On a bender, by Eduardo Blanco Amor. The protagonist and narrator, Cibrán, who is from a proletarian background, repeatedly makes use through the narration of the Galician set phrase “save for their blessed souls” – which people would often use whenever they compared people to animals, well aware of the sacrilegious connotations of such comparisons: thus, Cibrán writes that his mates, Gobs and Menaplenty, ate like swine, and then immediately makes it clear that their mates do have a blessed soul, while pigs do not.

Over the course of the novel, “save for their blessed souls” becomes a sort of drone, but in the end Blanco Amor shows that he’s also there in the novel as an author: the final time Cibrán makes use of this set expression, he twists it a little, and says that Menaplenty was like an animal “apart from the soul God put into him to no avail.” I don’t want to spoil the novel’s ending, but it will suffice to say that Blanco Amor’s addition is not just a clever twist with no consequences. By now, we are not even aware that the cliché is a cliché; it has become part of the narration.

—

Eva Moreda comes from Galicia but lives in Scotland, where she teaches and researches in the field of Music History at the University of Glasgow. She is a published, prize-winning novelist in Galician and has only recently started using English as her main writing language; she is currently working on two academic monographs about music under the Franco regime and a novel set during the Second World War. A short fiction piece was recently published in the anthology Writers at the Hunterian.

Follow her on twitter @TheDrRodriguez

Category: Being a Writer, Contemporary Women Writers, Multicultural Writers

Comments (13)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post

- Carpe YOLO | Paula Reed Nancarrow | September 1, 2014

Thank you. A very helpful post. And now I must get your book when it comes out in English.

Eva,

I love how you progress in this post from not liking cliches to realizing a favorite writer might be defined for his cliches … but escapes it (maybe because of his writing prowess?). Your book sounds fascinating.

-Martha

Thank you! It was a useful post, and I quoted from it in my own this week. http://paulareednancarrow.com/2014/09/01/carpe-yolo/. Given that cliches are the theme for this whole season’s performance, I may have to come back to it repeatedly.

The only problem with cliches is that a writer starts with them, they’re never going to rise above them and come up with an original story. Instead, they’re going to be competing with all the other writers who are doing the same thing.

Great point. Even though I may not want to read a book filled with clichés, a generous sprinkling of them induces a familiarity that makes me comfortable.

Which will I do now?

I was reading somewhere and was asked not to use cliches. They said the reason was because reading make an article boring.

check http://www.udookonjo.com

…and also what about the fact that what might be considered as a cliche in one culture might not be so in another? To view something from only one view-point is very limited..no? As someone who does not necessarily view literature from only the western point of view – I hold a completely diverse view on the use of cliches!

Hi Anjali, I think this is a very interesting point, and I wish I had had an extra 200 or 300 words to discuss it. There are certainly clichés which are country or culture-specific; for example, in the last 15 years or so, a sort of “Civil War memory” genre has developed in Spanish literature, with its own clichés. I personally find them tiresome, but I know that some non-Spanish people have found them interesting and informative (and, to be fair, some of the novels which use such clichés are well-written and tell interesting stories). In fact, it could be argued that certain well-known writers have made a career out of ‘re-branding’ national clichés from their own country for international consumption.

Hi Eva,

Thank you so much for responding – and you got my point totally! As a person from a different culture, even the way I ‘use’ the English language differently – it’s both frustrating and fun to discover these various undercurrents that exist, in the flow of language itself. But then, that’s what makes writing and reading such fun 🙂

Very insightful, Eva. I particularly liked your point about how cliches can, in certain ways, make work accessible to a wider variety of readers. A scenario that might seem trite to readers who are overly familiar with it might be “just the ticket” to capturing the attention of those who aren’t.

Thank you Anora! Being usually so grumpy about clichés, it was helpful to sit down and think about why is it that I dislike them and how to use them productively – so a great opportunity.

What a great piece! You’re an exciting writer to read Eva! Thank you so much for contributing to Women Writers, Women Books! You, from Galicia, where our Barbara Bos is from, but living in Scotland, where my father’s ancestors are from. – Anora McGaha, WWWB