From PhD Research to Fiction: The Struggles and Opportunities of Compiling and Editing “The Unpicking” for Commercial Publication

From PhD Research to Fiction: The Struggles and Opportunities of Compiling and Editing “The Unpicking” for Commercial Publication

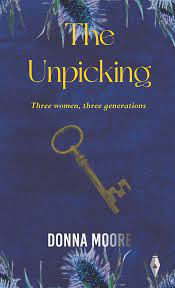

Historical novel “The Unpicking” (October 2023, Fly on the Wall Press) is the creative writing element of a PhD thesis which explores the role of women between 1870 and 1920, particularly marginalised women whose lives are often missing from the records. The book is divided into three parts (and three generations of women.

These stories are set over a century ago, but the long shadows of the past still have meaning and resonance today. Ultimately, ‘The Unpicking’ focuses on the commonalities across experiences that women faced, and, indeed, continue to face, in a world where they are disadvantaged and abused. They reflect wider concerns about power, sexual violence and inequality.

The period I have chosen to focus on for these novellas was one of great flux and upheaval which brought enormous changes in many aspects of women’s lives – economically, socially, politically and legally. Up until the 1870s, women were invisible in the eyes of the law once they married and were simply added to the husband’s possessions. As the nineteenth century advanced, voices campaigning for improvements in the property rights of married women and increased freedom for all women became louder. The results of campaigning were three Married Women’s Property Acts in 1870, 1874 and 1882. These Acts didn’t apply in Scotland and it was only in 1880 and 1881 that women in Scotland gained improved rights. The Birdcage starts in 1877, prior to both the Scottish Acts.

In terms of a husband’s control over his wife’s body, the nineteenth century was also a time when campaigners fought for the lunacy laws to be overhauled. The Birdcage has, as part of its plot, the concept of hysteria. By the second half of the nineteenth century, it was considered that any disease or abnormality of the uterus and ovaries could cause a range of symptoms from moodiness to insanity and I wanted to show how that formed part of the controls that women were subjected to.

The main part of my research for The Birdcage was on the archives of Stirling District Asylum, held at the University of Stirling. The records are fascinating, touching, sad, revealing and thought-provoking. A significant number of women were in the institution for many, many years. The case notes are pretty sparse and the number which end “Patient died today” is really sad.

I focussed on records from around 1890, even though that’s after my story takes place. One of the reasons for this was that the records seem to be better kept and more detailed around this time. Another reason is that the authorities began to use photographs in the records and I found these very powerful, helping me to connect with the women even more. In 1890, the patients seem to be examined every couple of months. After that, it’s about once a year unless there’s something happening with their treatment or situation. So these women get a couple of sentences a year devoted to them. I managed to trace one woman through several books of case notes from her admission in 1869 to her death in the Asylum 1919 and it made me really sad to think of her being there for fifty years.

I need to know the world my characters inhabit. For this reason, knowing the names of shops and businesses in a particular street, or the colour of a dress, or how much women might have been paid to fix hooks and eyes onto a piece of card is important to me. The Stirling District Asylum archives, give little or no context to the women who were patients there, but they are full of tantalising and serendipitous snippets of daily life, such as a goldfish bowl tampered with by one of the patients – a small detail which I have used in The Birdcage.

Bellsdyke Hospital – Records of Helen McNaughton, Stirling District Asylum Archives SD/1/4/29, Record No. 1778, pp.118-119

Why did I transform the research into a fictional narrative?

For me, fiction invites readers to consider complex issues in a way which allows varied perspectives and subtle nuances. Fiction acts as a way to communicate those perspectives and subtleties in a way which is entertaining. When we read any text we bring to it a whole kaleidoscope of meaning which is formed by our own experiences and viewpoints, our experience of other texts, and by society and culture.

There are many volumes of records for the Stirling District Asylum which I didn’t investigate. Would I find additional records for some of the women in their pages? What about other asylums, both public and private? Did any of them keep more detailed records? Or include letters and other writings from the patients themselves?

Historical crime fiction is a wonderful way to consider marginalised and unrecorded lives and the gaps in the archives. It’s also a great way of considering women’s position in society and I can point to present day inequalities through comparisons with the past. Historical crime fiction is a complicated genre to write because the requirements of the two genres need to be considered. In the context of crime, would some of the crimes I am writing about have been considered as such at the time? I can’t change historical definitions of crime, but I can have my characters comment on them from a social or moral point of view.

—

THE UNPICKING

“I had read enough mystery stories to know that girls who went out to meet strangers at night never came to a good end…”

“I had read enough mystery stories to know that girls who went out to meet strangers at night never came to a good end…”

Stirling, 1877. Lillias Gilfillan, a recently orphaned girl of sixteen, falls in love and elopes with a man who sees her as wealthy and naïve: ‘a little boat without its oars’. In a sea of rising debt and deception, Lillias must learn quickly, or drown.

Glasgow, 1894. Clementina knows little mercy living in a home for ‘wayward girls’. With the ‘Jingling Devil’ always lurking in the shadows and a child growing inside her, can she outrun him and save her best friend in the process?

Glasgow, 1919. Mabel is one of the first policewomen in Glasgow, on a mission to find a murderer. In doing so, she finds a web of corruption and now the ‘Jingling Devil’ wants her dead.

‘The Unpicking’ spans three generations of ‘hysterical women’ who take on systemic corruption and injustice, despite all odds.

“Phenomenally good. Donna Moore’s third novel is deadly serious. The three characters are strong and brave, for the situations they find themselves in. They use all their energy on trying to make things better; staying alive; but the world isn’t cooperating with them. But working together, women can do a lot.” – Ann Giles, The Book Witch

“With a wonderfully realised cast of characters and fine eye for detail, The Unpicking is grimy, exquisite and utterly compelling!” – Dr Zoë Strachan, University of Glasgow

“each lead character, in spite of their courage, strength and determination, has a gentleness at their core that it’s impossible not to become fond of” – Nigel Bird, author of the Southsiders series

“An utterly compelling story with three glorious women protagonists you’re rooting for as soon as you meet them. I loved it.” – Sarah Ward author of The Birthday Girl

BUY HERE

About the Author –

Donna Moore is the author of crime fiction and historical fiction. Her Her first novel, a Private Eye spoof called Go To Helena Handbasket, won the Lefty Award for most humorous crime fiction novel and her second novel, Old Dogs, was shortlisted for both the Lefty and Last Laugh Awards. Her short stories have been published in various anthologies. In her day job she works as an adult literacy tutor for marginalised and vulnerable women, facilitates creative writing workshops and has a PhD in creative writing around women’s history and gender-based violence. She is also co-host of the CrimeFest crime fiction convention and is a fan of film noir, 1970s punk rock and German Expressionist artists. The Unpicking is her third novel.

Donna Moore is the author of crime fiction and historical fiction. Her Her first novel, a Private Eye spoof called Go To Helena Handbasket, won the Lefty Award for most humorous crime fiction novel and her second novel, Old Dogs, was shortlisted for both the Lefty and Last Laugh Awards. Her short stories have been published in various anthologies. In her day job she works as an adult literacy tutor for marginalised and vulnerable women, facilitates creative writing workshops and has a PhD in creative writing around women’s history and gender-based violence. She is also co-host of the CrimeFest crime fiction convention and is a fan of film noir, 1970s punk rock and German Expressionist artists. The Unpicking is her third novel.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips