What Remains: Tanya Marquardt

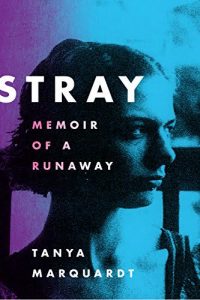

Tanya Marquardt is an award-winning playwright based in Brooklyn, author of the newly released memoir, STRAY: Memoir of a Runaway (published by Little A, Amazon’s literary and non-fiction imprint on September 1). Tanya’s story was recently featured in The Huffington Post and CBC, and her book has received early praise from Publishers Weekly.

Tanya Marquardt is an award-winning playwright based in Brooklyn, author of the newly released memoir, STRAY: Memoir of a Runaway (published by Little A, Amazon’s literary and non-fiction imprint on September 1). Tanya’s story was recently featured in The Huffington Post and CBC, and her book has received early praise from Publishers Weekly.

Told with raw honesty and strength, STRAY captures the moments of grace that help a young woman escape the psychic damage that can mar any kid who has to grow up too soon. After growing up in a dysfunctional and emotionally abusive home, Tanya ran away from home on her sixteenth birthday. Her departure was an act of rebellion and survival—and in the two years living on her own, she struggled with homelessness and addiction to drugs and alcohol while managing to attend high school. She found a chosen family in her fellow misfits, and the bond they form is fierce and unflinching.

A writing teacher’s praise saved Tanya from suicide and a life in the theater offered her purpose and refuge. But in the end, Tanya’s real savior was herself, where she found solace in her creative drive despite the instability of the world around her.

We’re delighted to feature an excerpt of her book.

WHAT REMAINS

“What are you writing there?”

My hip was leaning against a set of lockers. I was holding my diary open with my right hand, and I cradled a used copy of The Old Man and the Sea in my armpit while frantically writing in my diary with my left hand.

“Oh,” I looked up as the diary began to slide out of my hands.

Mr. Walecki, my english teacher, was taking me in, inquisitive with his head tilted to one side as if he were looking at something peculiar. I clutched my diary to my chest to keep it from slamming to the ground.

“A poem. I was writing a poem.”

“You’re a writer then?” he asked.

No one had ever asked what I was writing, not friends, not family, and never an adult. At drunken bush parties I would bellow my poems out loud to crowds of onlookers, things to shock, the dirtier the better, but no one had ever named what I was doing, had ever called me ‘a writer.’ It sent an electric buzz through my cheeks and I blushed.

“I guess so,” I answered.

“Oh, how wonderful,” Mr. Walecki peered into my diary like he was peering down a magic well. “Do you always draw pictures next to your poems?”

The diary was pressed against my body half open, the white unlined pages covered in scribbles, poems and pen drawings of vines, eyeballs, and faceless women.

“Well,” I looked down to see my poems, “sometimes, I mean, if it feels right. I don’t plan it or anything.”

“Best way,” Mr. Walecki said.

There was an uneasy silence and I began to gush, “I write a lot, I mean, I write all the time, poems and things mostly, they just come to me. They keep me up sometimes, I mean, you know, I can’t seem to do anything without these words coming into my head, they’re in there all the time. I write all the time. You know, I can’t stop it really.”

“I’d love to hear some.” Mr Walecki said.

I pulled the spiral binding of my diary into my sternum.

“Really?”

“Yes. How about Thursday, say twenty minutes into lunch hour. Come to my room. Would that be okay?”

“Okay.”

I asked myself in my head, Did I just say ‘okay’ out loud? and decided that yes, I did only it was a whisper and I wondered if Mr. Walecki heard me.

“Okay,” Mr. Walecki said, “Thursday it is.”

When Thursday finally came, I smoked two cigarettes one after the other so that I would have five minutes to get to Mr. Waleki’s classroom on time. The smoking was a tactic to try and slow my labored breathing. I had spent the week pouring over my diary and had picked five poems I wanted to read. Most of them were untitled and none of them were upbeat. I loved them.

I stared up into Mr. Waleki’s room. The sunlight hit his window at a sharp angle and reverberated off the glass. It blinded me. I let my cigarette dangle from my mouth, taking my usual hauls, the smoke billowing up into my face, and ash dropping off the tip onto the pebbled ground. I flipped through the torn pages of my diary, reading each poem under my breath. I was trying to find an order to the five I had selected, anxiously reading and re-reading each stanza, my palms sweaty, my heart beating so fast that my fingers tingled.

After my second smoke, I launched myself up the steps. When I arrived at Mr. Waleki’s room, I was out of breath and he was slowly unwrapping the wax from around a tuna fish sandwich. He also had a few cookies, a steel thermos of tea, and a kid’s container of orange juice.

“Hello,” he said.

I nodded quickly in his direction.

“You look flustered. Come in.”

Feigning confidence, I strode into the room. I wasn’t sure where to sit.

“If you don’t mind, I’d prefer you sit beside me. I’d like to see the way you lay out the poems on the page and embarrassingly, I’m a little hard of hearing.”

He shrugged to himself, accepting his age.

“Would that be alright?” he motioned to the chair beside him, empty and waiting.

I took a deep breath, made horse-like strides over to the chair and sat down.

Laying my diary in my lap, I clutched the top edge of the paper, wrapping my fingers around the cardboard cover and waited for Mr. Walecki to say something. I was so excited that I felt like barfing and pissing my pants all at once. I wanted to read the poems aloud but had no idea how to start.

Mr. Walecki took a long bite of his tuna sandwich, slowly chewing with his brow furrowed.

“Did you know that when people first started to write poems, they memorized them?”

I shook my head, enraptured.

“Yes, they memorized the poems and later, when they wanted to share the poems, they would recite them out loud. Poems are meant to be heard you see. That’s why poets play with the way the poems are laid out on the page, the way they look. It says something to the reader about how to speak the words out loud. It says something about the rhythm of words.”

Mr. Walecki hunched down in his chair and lowered his voice.

“I love that,” he said, his eyes sparkling.

“I love that too,” I blurted out.

I had no idea if what he was saying was historically accurate but I didn’t care. All I could imagine were minstrels crying out in Old English from delicate parchment in town squares and knights yelling up through candlelit windows hoping that their love poems reached their lady-loves to beckon them out onto their veranda, like in Romeo and Juliet.

“So then, let’s have a listen,” he motioned to the diary balancing hands-free on my scrawny knees.

For the next six months, I visited Mr. Walecki. I read my poetry to him and he listened, leaning back in his chair with his arms folded on top of his belly, his head tilted to one side, and his bifocals clutched between the fingers of his left hand. His eyes would close like he was having a nap on a Sunday afternoon, perking up only to give instruction.

“Slow down please,” he would say or, “Could you read it once more?”

After reading the poem out loud, he would snap out of his half-waking state and sit up in his chair with a sharp inhale.

“Now why did you chose this word?” he would ask, or “Why did you put a line break in the middle of this sentence?”

We would go over grammar, spelling, and layout, while discussing possible edits. He never asked about the context for the writing and he showed no signs of alarm, shock, or disgust at the topics of suicide, hatred, loneliness, desperation, or despair. For this, I was grateful. After our poetry lunch breaks, I would go to the bathroom and cry, letting out big wet teardrops that made echoing sounds as they tapped against the hard linoleum floor.

—

About STRAY: MEMOIR OF A RUNAWAY

“Marquardt’s memoir is a brutally honest reflection on her fraught adolescence and journey of self-realization.” – Publishers Weekly

“The highly expressive narrative is often brutal and raw, a combination of truth and penance, and it feels like a confession leading toward sanity and forgiveness.” -KIRKUS

After growing up in a dysfunctional and emotionally abusive home, Tanya Marquardt runs away on her sixteenth birthday. Her departure is an act of rebellion and survival – whatever she is heading toward has to be better than what she is leaving behind.

After growing up in a dysfunctional and emotionally abusive home, Tanya Marquardt runs away on her sixteenth birthday. Her departure is an act of rebellion and survival – whatever she is heading toward has to be better than what she is leaving behind.

Struggling with her inner demons, Tanya must learn to take care of herself during two chaotic years in the working-class mill town of Port Alberni, followed by the early-nineties underground goth scene in Vancouver, British Columbia. She finds a chosen family in her fellow misfits, and the bond they form is fierce and unflinching.

Told with raw honesty and strength, Stray reveals Tanya’s fight to embrace the vulnerable, beguiling parts of herself and heal the wounds of her past as she forges her own path to a new life.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing