When a Book Release is Truly a Release

CameraRAWPhotography

I wasn’t sure I’d ever finish writing my memoir.

The Art of Misdiagnosis is centered around my mother’s suicide; she took her own life exactly one week after I gave birth to my youngest child in 2009. I felt great urgency to try to make sense of that charged, disorienting time, but the story felt so big and messy and painful, I thought it might take the rest of my life to find the right words, the right form, to contain it. When I finished the first draft—something that not long before had felt impossible—it took me a while to stop weeping, stop shaking.

With each successive draft, I felt myself grow lighter. While I wrote that first draft for myself—to purge, to process, to bear witness—I became more aware with each new draft that my story could have a life outside of me, that my story could become a source of connection instead of just personal anguish. And while I tried not to think of readers as I wrote the first draft, tried to imagine no one would ever read it so I would hold nothing back, with each new draft, I thought: how can I make it clearer for people who weren’t there? What does the reader need to know? That first draft was catharsis; the next drafts were craft, were art, were invitation.

This book release felt different from any I had experienced before when I published novels or books of poetry or craft. It was terrifying to put such a vulnerable story in the world, but it was also liberating. It was the first time a book release truly felt like a release inside my heart. It was a profound experience to pick up the book, to see my story coalesced into a shape outside my body—something I could press to my heart; something I could put down, put away.

And I could feel how the burden of the story lessened when other people picked up the book, how readers helped to hold my pain, how my book helped them carry and release their own stories. I’m grateful a friend who wrote a memoir about depression prepared me for the fact that I would become a magnet for people’s stories of suicide loss—she had been blindsided by people coming to her in crisis when she promoted her book, and cautioned me to prepare my heart for other people’s pain, to have resources available to hand out when needed. I obtained some hotline cards from the American Foundation for the Prevention of Suicide, which has great resources for suicide loss survivors as well as for those contemplating suicide, and made sure to have them on hand as I toured about. Thus fortified, I found it a great honor and gift to receive other people’s stories.

I didn’t always fortify myself in other ways when I promoted the book, however. I thought I’d be okay talking about the most traumatic time in my life over and over again because I had spent so much time immersed in the story, thinking about it, writing about it, letting myself feel what I needed to feel as I made my way through the project. Sharing it out loud repeatedly with an audience was deeply meaningful, but it also stirred up a lot of emotion (plus, as an introvert, having to be “on” so regularly is taxing in itself). I found myself dreaming about my mom and waking up sobbing, something that hadn’t happened in years.

I found myself having a panic attack in a hotel room. I told myself to prioritize self care, to make sure I was eating enough, sleeping enough, but I didn’t always do a great job of this as I toured with the book, and it started to take its toll—I started to feel like a raw nerve, like I was walking around without enough layers of skin. It meant so much to me when my sister flew in from Toronto to attend a reading in Pasadena on the anniversary of our mother’s death, just down the street from where she died. My writing this book had not been easy for my sister, and having her there to support me fortified me more than any meal or night of sleep ever could.

And I found myself feeling connected to my mom in surprising ways. The day my memoir was released, I received a piece of mail—an invitation to a time share event—addressed to my mom; I had never received mail for her at my current address, a home my husband and I bought seven years after she died, and seeing her name arrive at my door unexpectedly, on that day of all days, felt like a blessing, an invitation to share time with her.

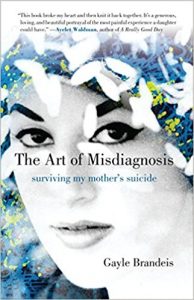

That evening, on the way to my book launch event, a giant cloud shaped like a crow—a bird I’ve associated with her ever since her death—appeared in the sky, and that made her feel close, too. I’ve felt her presence in other synchronistic ways as I’ve promoted the book, and whether this has just been my mind looking for her, looking for patterns, for meaning, or whether there’s been something more mysterious at play, it’s done my heart good. I had written the memoir in large part to try to understand my mom—I started the project with a lot of anger toward her, anger that eventually morphed into compassion, into appreciation; by the time The Art of Misdiagnosis was released, I was ready to release some of her hold on me. I was ready to look at her picture on the cover of the book and finally meet her gaze.

—

Facebook: www.facebook.com/gayle.

About THE ART OF MISDIAGNOSIS

Award-winning novelist and poet Gayle Brandeis’s wrenching memoir of her complicated family history and her mother’s suicide

Gayle Brandeis’s mother disappeared just after Gayle gave birth to her youngest child. Several days later, her body was found: she had hanged herself in the utility closet of a Pasadena parking garage. In this searing, formally inventive memoir, Gayle describes the dissonance between being a new mother, a sweet-smelling infant at her chest, and a grieving daughter trying to piece together what happened, who her mother was, and all she had and hadn’t understood about her.

Gayle Brandeis’s mother disappeared just after Gayle gave birth to her youngest child. Several days later, her body was found: she had hanged herself in the utility closet of a Pasadena parking garage. In this searing, formally inventive memoir, Gayle describes the dissonance between being a new mother, a sweet-smelling infant at her chest, and a grieving daughter trying to piece together what happened, who her mother was, and all she had and hadn’t understood about her.

Around the time of her suicide, Gayle’s mother had been working on a documentary about the rare illnesses she thought ravaged her family: porphyria and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. In The Art of Misdiagnosis, taking its title from her mother’s documentary, Gayle braids together her own narration of the charged weeks surrounding her mother’s suicide, transcripts of her mother’s documentary, research into delusional and factitious disorders, and Gayle’s own experience with misdiagnosis and illness (both fabricated and real). Slowly and expertly, The Art of Misdiagnosis peels back the complicated layers of deception and complicity, of physical and mental illness in Gayle’s family, to show how she and her mother had misdiagnosed one another.

Gayle’s memoir is both a compelling search into the mystery of one’s own family and a life-affirming story of the relief discovered through breaking familial and personal silences. Written by a gifted stylist, The Art of Misdiagnosis delves into the tangled mysteries of disease, mental illness, and suicide and comes out the other side with grace.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Thank you Gayle. I too will be more prepared for readings. Your advice is priceless, as I wasn’t at all prepared at my book’s release. Bravo for delving in so deeply, and coming out the other side, with grace.

It sounds like a wonderful memoir, Gayle, and I so appreciate the heads up about the book release journey. When my time comes, I’ll be more prepared about what to expect. Thanks for sharing your story.