Publishing : Has anything changed since the 19th century?

While researching my new biography, La Belle Créole, I unexpectedly discovered the vibrant literary world of early nineteenth-century Paris. And surprisingly, that world was not that dissimilar from our own.

Alina Garcia Lapuerta

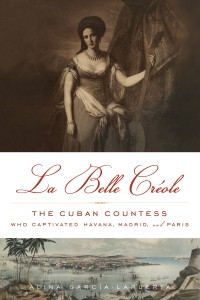

My subject, Mercedes Santa Cruz y Montalvo, Countess Merlin – was a fascinating, multitalented woman. After a complex and tumultuous early life in Cuba and Spain, she found herself exiled to Paris in the crumbling last days of Napoleon’s empire. Here, she created a celebrated musical salon which hosted the artistic world, politicians and the crème of society. Mercedes also began a writing career which she would continue until her death in 1852.

I admit that I knew little of this literary environment and so I started with biographies of contemporary figures: Balzac, George Sand, Princess Cristina de Belgiojoso and the Marquis de Custine. These gave me context, while reading the surviving correspondence between Mercedes and her publishers and literary collaborators provided more specific details.

What I learned surprised me. Mercedes’ literary world was not that different from our own.

- Celebrity was a useful resource

Mercedes began her literary career with her memoirs of her early days in Cuba and Spain. She was well-known at the time in the French press for her beauty, voice, salon and benefit concerts. Her first book was published “privately” for her friends, but sold out at bookstores – as the equivalent of Publishers Weekly described it (Yes, even back then there were journals dedicated to the publishing trade).

Riding on that success, she published a related novella in 1832 and her expanded memoirs in 1836. The latter was a full-on literary endeavor. It was clear that both she and the publisher thought that her own fame, as well as a book liberally sprinkled with historical figures and exotic locations, was a sure bestseller. Another publisher later negotiated to have her write her impressions of well-known society figures – the ultimate insider’s tale.

La Belle Creole

All of this is familiar in today’s celebrity-fueled culture. The fact that Mercedes did have a compelling story to tell and had a flair for writing was an added benefit. But it is also telling that publishers even negotiated for the right to print her portrait in the books – to add to its overall attractiveness.

- Networking and media contacts.

Even in 1836, people needed reviews in influential journals, and sought publicity in the press in order to ensure success. No one was above pulling strings, calling in favors – working their contacts – to achieve this goal and create a buzz. Even the great Balzac was known to have penned one of his own favorable reviews!

Mercedes was friends with some of the leading journalists and editors of the day. Her name constantly appeared in society columns – especially in the one written by Delphine de Girardin, the wife of the editor of La Presse. La Presse would also serialize some of Mercedes’ work (a popular method to initially publish novels, as well as generate interest in an upcoming book).

When authors were serialized, they often fought for the right placement or the key moment to go to press. Mercedes once angrily complained about the timing of her serialization – it needed to appear when society was in Paris – her key market.

Whether a review was commissioned by an important journal could be influenced by friendly relations. This could also be true of influential reviewers. In Mercedes’ case, her memoirs were reviewed by George Sand through the intervention of a mutual friend. That particular review was not all that Mercedes hoped for – but it was generally positive, and given George Sand’s popularity, it was a real coup.

- Money mattered: advances, income and pirating

In Mercedes day, writers received a set amount for specific editions and print runs. Additional editions received additional payments. The more successful the author, the higher the payments. Serialization could also add to the income stream, as could foreign rights. Mercedes had one Spanish edition of her best known work, Viaje a La Habana and an English version of her biography of the opera diva, La Malibran.

Foreign publications were wonderful, but Mercedes and other writers, including Balzac, were very concerned about illegal editions of their works. As people might worry today about illegal digital editions, in Mercedes’ day they dreaded Belgian publishers.

Many of these cheap editions (widely available throughout Europe) were unauthorized and paid no royalties to the authors. Balzac was one of the most vocal critics of this situation.

- Publishing was a long process: delays, deadlines and proofs

In Mercedes’ day pen and paper reigned. Clean copies were made and submitted by either messenger (if they were both in Paris) or via mail. The publisher might comment or simply provide the galley proofs – again delivered by messenger or mail. Mercedes would then mark them up and repeat the process. All of this – as you can imagine – took time.

Deadlines existed – and sometimes deadlines were not met. Angry letters would fly, and in the worst case, litigation could follow. Editors could also ask for changes. Mercedes’ last novel, published posthumously, was actually begun years before for another publisher. After submitting the first part, that publisher offered extensive advice for maintaining the pace (critical in serialization), and incorporating more local color and exotic details to intrigue the reader.

Deadlines existed – and sometimes deadlines were not met. Angry letters would fly, and in the worst case, litigation could follow. Editors could also ask for changes. Mercedes’ last novel, published posthumously, was actually begun years before for another publisher. After submitting the first part, that publisher offered extensive advice for maintaining the pace (critical in serialization), and incorporating more local color and exotic details to intrigue the reader.

So while it may seem a long way from the era of paper, pen and traveling desks, things haven’t changed too much. We may have technology, blogs and twitter, but networking, reviews and publicity are still critical. Editorial comments, proofs and deadlines remain the bedrock of traditional publishing. Concerns over royalties and pirating continue. Even nineteenth-century literary stars had to earn a living.

—

Alina García-Lapuerta, a native Spanish speaker, was born in Cuba. A graduate of Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, she is member of Biographers International Organization, and The Biographers’ Club of London. Based in London with her Spanish-American husband and their two children, Alina still spends considerable time in South Florida.

Find out more about Alina on her site www.alinagarcialapuerta.com

Follow her on twitter @GarciaLapuerta and Facebook Alina-Garcia-Lapuerta

Category: On Publishing

Comments (3)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post

- No Wasted Ink Writer’s Links | No Wasted Ink | July 13, 2015

Fascinating!

What a thoughtful and well-written article, Alina! Thank you for sharing your insights about a fascinating time in history. I guess the more things change, the more they stay the same.