Plot-driven or Character-driven?

I love reading books about writing. It is my number one displacement activity when I should be working on my novel. However, it bugs me how some how-to books split plot and character. Some books even divide genres into plot-driven and character-driven and say that the plot-driven novels are more likely to be ‘commercial fiction’ and the character-driven ones ‘literary fiction’.

I love reading books about writing. It is my number one displacement activity when I should be working on my novel. However, it bugs me how some how-to books split plot and character. Some books even divide genres into plot-driven and character-driven and say that the plot-driven novels are more likely to be ‘commercial fiction’ and the character-driven ones ‘literary fiction’.

Say you want to write a book about terrorists threatening to blow up one of the Canary Islands because that will set off a tsunami and destroy the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. In that case, you start with a – rather far-fetched – plot and you could define this as plot-driven writing. Clearly you still need to populate your book with characters. Maybe you’ll have some terrorists, someone (or a team) trying to stop them, maybe a scientist who is aware of the danger, a few potential victims and you make it personal by having the husband of the scientist stuck on the island. But your characters are there to support this plot that you’ve created.

On the other hand, maybe the story that you want to tell is of a widow whose husband recently died. The book is about how she deals with her grief. You start with the character. Then you need to figure out a plot. Maybe she has never worked and there was no insurance and now she needs to figure out how to pay the mortgage. The plot can be how she gets a job. This novel will be much more character-driven.

So in theory that’s all neatly divided. But my experience of writing my novel has been very different and I have found that plot and character are much more intricately interwoven and seem to grow and expand together.

I write crime fiction, which most people probably think is plot-driven. However, I want my crime fiction to be realistic in terms of the criminals having a motive (and method) that is true to life. Everybody has to behave true to their character and therefore the characters cannot be cardboard cut-outs. Sophie Hannah described this in a talk that I attended as creating characters that are willing to do what the plot needs them to do.

I write crime fiction, which most people probably think is plot-driven. However, I want my crime fiction to be realistic in terms of the criminals having a motive (and method) that is true to life. Everybody has to behave true to their character and therefore the characters cannot be cardboard cut-outs. Sophie Hannah described this in a talk that I attended as creating characters that are willing to do what the plot needs them to do.

In one of her novels, she has a couple in a hotel room about to have sex for the first time. Before getting down to the act, they decide to swap secrets and the man’s secret is that he once killed someone. Now the majority of people in that situation would say: ‘gosh, is that really the time? I’ve got to get going.’ Or they might run out and call the police. Sophie Hannah’s main character doesn’t do this. She stays with her boyfriend and investigates the murder. The writer had to work hard to create a character who would stick with her boyfriend even after he had confessed to a murder. Without the right characters, the plot just wouldn’t work.

I come at it from a different angle. My father used to be a police detective in the Netherlands and what I am fascinated with is what the close proximity to crime does to the people investigating it. Even as a child I realised that my father, a now-retired police detective, didn’t see the world the way other people did. In his day-to-day experience, he would meet criminals, victims, suspects and his colleagues. The ‘normal’ people that the majority of us deal with were a minority in his working life. So in my novel I want to show how my main character is changed by every crime she investigates.

I come at it from a different angle. My father used to be a police detective in the Netherlands and what I am fascinated with is what the close proximity to crime does to the people investigating it. Even as a child I realised that my father, a now-retired police detective, didn’t see the world the way other people did. In his day-to-day experience, he would meet criminals, victims, suspects and his colleagues. The ‘normal’ people that the majority of us deal with were a minority in his working life. So in my novel I want to show how my main character is changed by every crime she investigates.

My father also gave me the idea for the book. A few years after he’d retired, police officers from Amsterdam visited him to re-open the investigation of a murder that had stayed unresolved for over a decade. Even though I completely changed the victim and the crime, that image of the retired police detective being asked questions about this old case stayed with me. I kept (a version of) the character but changed the plot.

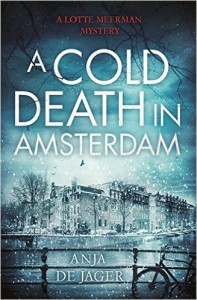

So my novel started with two people: a retired police detective whose case gets reopened and his daughter Lotte Meerman, a police detective in Amsterdam, who has to decide how far she can trust her father. Is that the plot or are those the two main characters? Maybe you could describe it as character-driven crime fiction but I find it difficult to separate plot and character. I do plot very carefully and I love plotting almost as much as I love creating characters.

I want the reader to be able to work out ‘who did it’ together with my main detective. But as I write, my plot often changes. I might have planned for someone to act in a certain way and as I get deeper into the story and flesh the character out, I think: no, they would never do a thing like that. I will have created a character who will no longer do what the plot needs her to do. In that case, I do not change the character, I rework the plot.

That’s how plot and character grow together, intricately linked, and I’m sure that for many other writers it is the same. Things are never are neatly divided as the theory suggests. Plot or character, which comes first? It’s really like the chicken or the egg.

—

Anja de Jager is a London-based native Dutch speaker who writes English. She draws inspiration from cases that her father, a retired police detective, worked on in the Netherlands. Anja has written a number of short stories, some of which have been shortlisted for Mslexia. She is currently working on the next Lotte Meerman novel.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Useful article, Anja. I’ve just returned to the rough first draft of what I hope will be my third novel. I thought I’d read it through, then do some intense plotting, before beginning to write the second draft. But that’s not what’s happened; instead, I’m revising that first draft and sharpening up on both plot and character in the process. I have a good idea of what drives my characters, and I know where the plot has to go, but I need to go deeper, and that will only come through and interaction between the characters I’ve assembled and how they behave.

Your background as the daughter of a police detective sounds really interesting, and a great angle from which to develop your crime series. Good luck with that!

What you’re describing is part of the definition of the different genres. Readers have certain expectations when they buy a different genre–but most writers don’t have a good understanding of genre. They just think they do. In fact, the biggest danger is letting a writer’s preference of one element dominate a story and overbalance out of a reader’s preference. That puts it in a different genre entirely.

An example is a romance writer who wants to try writing fantasy. So she plops a romance in a fantasy–has strong characterization, some fantasy world. Is that a fantasy or a romance? It’s a romance, because it overbalances on characterization. Fantasy’s top element is always the world–that’s what readers come to the story for.

The gist of all of this is that there is NO genre that favors plot as its top element. Mystery and romance are character; the rest of the major genres are Setting.