A Lost Literary Foremother: Constance Fenimore Woolson

About the time I was trying to decide if I could be a writer I started to wonder, when did women first have the nerve to commit themselves to careers as serious authors and to say, despite few female role models to follow, I can succeed at this as well as men? I wondered because, in the 1990s, it still seemed like such a daring and difficult thing to do.

About the time I was trying to decide if I could be a writer I started to wonder, when did women first have the nerve to commit themselves to careers as serious authors and to say, despite few female role models to follow, I can succeed at this as well as men? I wondered because, in the 1990s, it still seemed like such a daring and difficult thing to do.

I wasn’t sure I could do it. But the question still haunted me. And when I decided to go to graduate school and make a stab at becoming a professor (another kind of less-travelled road for women), I knew I had to try to answer it.

I assumed I would find my first examples of women writers committed to serious art in the Modernist period. But the more I looked, the further back I went until I landed in the Civil War era and the late-nineteenth century. There I found a number of women writers who sought serious recognition and devoted their lives to achieving it, at least for a while. I wrote a dissertation about them and a scholarly book called Writing for Immortality, published in 2004.

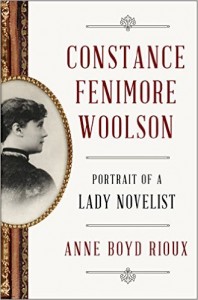

But I couldn’t stop there. One of those writers stayed with me. Her name was Constance Fenimore Woolson (1840-1894). If you have heard of her, then you have probably read Colm Toibin’s fine novel The Master, about Woolson’s friend Henry James, in which she makes a few appearances. There is also an outside chance that you read her story “Miss Grief” in a college class on women’s or American literature, since it is included in college literature anthologies.

But for the most part Woolson is known primarily by a small group of scholars trying to keep her name alive. I am one of them and decided it was time to bring her out of the insular academic world and into the limelight. My real hope is not only that she will be read by general audiences once again but also that women writers will find in her a lost literary foremother and will be inspired by her example.

When we think of women writing in the nineteenth century, images come to mind of Emily Dickinson, who hid herself and her poetry from the world; the Brontë sisters who were deprived of experience and died young; or George Eliot, who had to masquerade as a man to win respect. It is important to me that women writers and readers today know that there were other kinds of women writers in the nineteenth century who had successful careers and fulfilling lives. Woolson is, in my book, the most interesting and accomplished among them.

Digging through old reviews and letters, I was thrilled to learn that Woolson was hailed by critics, even called America’s “novelist laureate” by the Boston Globe, and given an exclusive contract with Harper & Brothers, who published all of her novels (under her own name) in the prestigious Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. She was often compared to Henry James and George Eliot and considered one of the foremost American writers of the nineteenth century. She also traveled the world, living all over the eastern U.S.—from the Great Lakes to New York to Florida—and Europe—primarily England, Switzerland, and Italy. She even lived in Cairo for three months, by herself.

Woolson dared to live an independent life as an author at a time when such lives were only available to men. She had no powerful man to encourage and love her, as Eliot had George Lewes. She did it all on her own. Her remarkable achievement, however, is almost entirely unknown today.

Those who have heard of Woolson know more about her death than her vibrant life. They have heard that she committed suicide in Venice and that somehow her friend Henry James was to blame. It has been assumed that she must have decided to end her life because of the neglect she suffered as a writer, much like the female protagonist in her most famous story “Miss Grief.” Or worse, critics have believed that she committed suicide out of unrequited love for Henry James. Neither is true. She chose to end her life when her health was deteriorating and she became convinced that she would not be able to write another novel. Her pen was everything to her—livelihood and identity. Without it, she could see no future.

Those who have heard of Woolson know more about her death than her vibrant life. They have heard that she committed suicide in Venice and that somehow her friend Henry James was to blame. It has been assumed that she must have decided to end her life because of the neglect she suffered as a writer, much like the female protagonist in her most famous story “Miss Grief.” Or worse, critics have believed that she committed suicide out of unrequited love for Henry James. Neither is true. She chose to end her life when her health was deteriorating and she became convinced that she would not be able to write another novel. Her pen was everything to her—livelihood and identity. Without it, she could see no future.

Rather than cast Woolson as another Ophelia and view her life as a failure because of how it ended, we should recognize her life as a success. It wasn’t a bed of rose–she suffered the deaths of many family members and friends, she struggled to gain the respect of her male peers (including James), and she was often lonely. But what I see in her life is a beautiful tenacity in the face of so many obstacles. Her example should inspire us. She lived independently, traveled widely, and was recognized as one of the most accomplished writers of her era. Writing her life story has been one of the highlights of my life. I don’t want another generation of women writers to be deprived of her example.

—

Anne Boyd Rioux is an English professor at the University of New Orleans. She is the author of Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist and the editor of a collection of Woolson’s stories, Miss Grief and Other Stories, with a foreword by Colm Toibin, both published by W. W. Norton. (They will come out March 22 in the UK.)

You can find Anne online at http://anneboydrioux.com/, or on Facebook and Twitter (@AnneBoydRioux). She also has a newsletter called The Bluestocking Bulletin, which profiles a little-known woman writer each month (https://tinyletter.com/abrioux).

Category: On Writing

I didn’t realize how starved I was as a writer until I started reading your book. I’m less than 100 pages in and already the book is covered with stickies, highlights, notes and exclamation points. Last night I had to stop reading because my eyes were so tired but I felt like I had feasted on prime rib. Your book reminds of me of Madeleine Stern’s bio on Louisa May Alcott, written from the point of view of a writer and directed at writers. It is therapy, it is education, it is much needed food for this writer who didn’t even realize she was hungry! Thank you.