Multilingualism and Writing

When I was eleven years old, my parents decided to up and move to another country.

When I was eleven years old, my parents decided to up and move to another country.

Quebec was not the original destination they had in mind; in fact, I didn’t know such a place even existed until my parents told me we were moving there.

After that, I dug through a stack of old life and style magazines—the closest equivalent that post-Soviet Russia had, with never-before-seen gaunt models flaunting thousand-dollar dresses my family would never be able to afford, interspersed with spreads of New Russians’ luxurious decorated houses and exotic travel destinations.

In one of the issues, I found the article on Montreal. There was something about Old Europe in the heart of North America, with pictures of skyscrapers next to those of terraces covered in flowers, horse-drawn carriages, and a man dancing on stilts on the cobblestones of the Old Port. It still meant absolutely nothing to me, but I cut out the pictures and stuck them on the wall above my bed with some play-doh.

The reality of Montreal turned out to be different. It was less flower-strewn terraces and champagne and more low-ceilinged apartment in the not-so-good part of town, in a building that perpetually smelled like cooking grease. On my way to and from school, I’d get catcalled and harassed by men sitting on low-hanging balconies of similar slums.

It was the best life I ever had up to that point.

Always an avid reader (and fledgling writer), I was only allowed to bring with me my absolute favorite books, because most of them would simply not fit into the luggage. So I brought my favorite Russian children’s books, my notebooks, and my diaries. But I would soon find out that they were as out of place here as I was.

In school, they first send immigrant children to a special class where they only learn French. (Language laws in Quebec only allow immigrants to attend a French-language school.) Naturally, we ‘welcome class’ students were not so welcome: we were the scapegoat for mockery and abuse by the locals, who all seemed to unattainably cool to me they might as well have been from another planet, not another country. Their clothes, their hair, the effortless way they spoke French just so, as opposed to my awkward complete sentences that never sounded right—I understood right away it would take more than eight months of intensive language classes to make me fit in.

French books, I realized, were also not my friend. I remember a YA novel we were assigned in seventh grade, when I started regular school: there was a girl who was supposedly thirteen, like myself. But her family was different from mine: her parents had no problem with her wearing makeup and dating. And she had a boyfriend, something I could only daydream about. Barely being able to understand Quebec-French colloquialisms was bad enough; this was a character I could not relate to on any level, and her problems seemed at best trivial to me.

That’s when a friend gave me a fantasy novel in English. Language difficulties aside, being able to escape from the real world altogether was nice. Finally having found something I liked, I did what any young teenager would do: I tried to write my own.

Writing, at first, was a frustrating experience. The words of my native language already started to slip away from me—I was making mistakes where I never would have a year ago, and my sentences were clunky. But French and English were not yet within my grasp: everything I wrote felt didactic and flat. I didn’t have a feel of the language or the text I was writing. I abandoned it for a few more years.

Gradually, I got back to reading, in English and French this time. I got the hang of the culture, so the settings and characters didn’t seem so alien anymore. I got back to writing, too—within a year, I beat my native-French-speaker classmates at both the spelling test and the essay competition. After that, I never left books out of my life again.

I wish I could say there was some great moral to the story, that it made me stronger and better, that it paid off in the end, that the bullies saw the error of their ways, but there really isn’t. It would be another decade before I tried to write for publication, and that’s a separate saga all on its own. And sure, to this day my beta readers, critique partners, and (heaven forbid) editor sometimes point out non-English idioms in my manuscripts (it’s never not mortifying, thanks for asking). But what I did get out of it is a really good memory and an extensive vocabulary. And I found a lot of good books along the way.

—

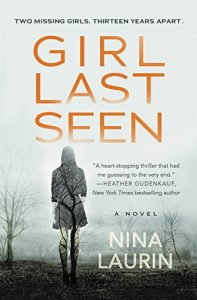

About GIRL LAST SEEN

Two missing girls. Thirteen years apart.

Two missing girls. Thirteen years apart.

Olivia Shaw has been missing since last Tuesday. She was last seen outside the entrance of her elementary school in Hunts Point wearing a white spring jacket, blue jeans, and pink boots.

I force myself to look at the face in the photo, into her slightly smudged features, and I can’t bring myself to move. Olivia Shaw could be my mirror image, rewound to thirteen years ago.

If you have any knowledge of Olivia Shaw’s whereabouts or any relevant information, please contact…

I’ve spent a long time peering into the faces of girls on missing posters, wondering which one replaced me in that basement. But they were never quite the right age, the right look, the right circumstances. Until Olivia Shaw, missing for one week tomorrow.

Whoever stole me was never found. But since I was taken, there hasn’t been another girl.

And now there is.

—

Nina Laurin is a bilingual author of suspenseful stories for both adults and young adults. She got her BA in Creative Writing at Concordia University, in her hometown of Montreal, Canada.

Find out more about her on her Website https://thrillerina.wordpress.com/

Follow her on Twitter https://twitter.com/girlinthetitle

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing