Of Fathers and Daughters: The Thriller as Tragic Love Story

I adored my father when I was growing up. I was a natural tomboy, my father’s shadow. I was the middle of three girls, and my father called me “Sam”—short for “Samuel,” and not “Samantha”—and I was more than happy to become his only “son.” My father taught me how to hammer a nail and use a handsaw, and when I got older, his circular saw and electric drill.

I adored my father when I was growing up. I was a natural tomboy, my father’s shadow. I was the middle of three girls, and my father called me “Sam”—short for “Samuel,” and not “Samantha”—and I was more than happy to become his only “son.” My father taught me how to hammer a nail and use a handsaw, and when I got older, his circular saw and electric drill.

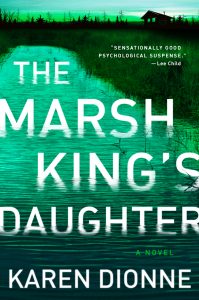

Like the narrator in my psychological suspense novel, The Marsh King’s Daughter, I copied my father’s mannerisms, his speech patterns, his walk. “It wasn’t worship,” says my narrator, Helena, of her regard for her father in the book, “but it was close. I was unabashedly, absolutely and utterly in love with my father.”

But unlike my father, Helena’s father doesn’t deserve her love. Jacob Holbrook is a cruel, demanding man; a narcissist, who thinks the world revolves around him; a man who kidnapped Helena’s mother when Helena’s mother was a teen and kept her hidden as his wife for fourteen years in the remote cabin in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula wilderness where Helena was born.

Helena knew nothing of this when she was growing up. She loved her father, and accepted her situation as normal because she didn’t know otherwise. Jacob teaches Helena how to track, to hunt, to snowshoe, to swim. He tells her the names of the birds, the insects, the plants, the animals, and shares the marsh’s endless secrets: a cluster of frog eggs floating on the still pond water beneath an overhanging branch, a fox den burrowed deep into the sand on the side of a hill. He teaches her how to sharpen her knife and skin a rabbit and button her shirt and tie her shoes—in effect, using her natural interests to manipulate her and shape her into a miniature version of himself.

It’s not until Helena grows older and begins to develop her own moral compass that she questions some of the things he does: his excessive hunting and trapping; his brutality toward her mother and herself. This is what makes her situation so heartbreaking: her father has taken advantage of the natural love a child has for a parent and twisted it to his own ends. In that sense, she is as much his captive as her mother, though she doesn’t yet know it.

As I grew older, I too, began to see my father’s flaws. But that didn’t diminish my love for him, and this is how I wanted to depict Helena in the novel. Yes, she grows up in terrible circumstances; yes, her father is without question a monster. And yet, for a time, “before everything fell apart,” as she puts it, her childhood was truly happy.

I’ve always been fascinated by people who rise above a less-than-perfect childhood, and wanted to explore this within the context of a story that was stripped down, even extreme. Without the moderating influence of other adults—teachers, grandparents, neighbors—and with a mother who was so traumatized she had all but checked out, Helena has no way to judge what is normal behavior and what is not. If her father occasionally punished her in ways that any other parent would consider abusive, “He was only teaching me a lesson I needed to know.”

Even as an adult, Helena makes excuses for his behavior. “After we left the marsh,” she says, “everyone expected me to hate my father for what he did to my mother, and I did. I do. But I also felt sorry for him. He wanted a wife. No woman in her right mind would have willingly joined him on that ridge. When you look at the situation from his point of view, what else was he supposed to do? He was mentally ill, supremely flawed, so steeped in his Native American wilderness man persona he couldn’t have resisted taking my mother if he’d wanted to.”

When her father kills two guards to escape from the maximum-security prison near her home, Helena concedes that “a part of me—a part no bigger than a single grain of pollen on a single flower on a single stem of marsh grass, that part of me that will forever be the little pigtailed girl who idolized her father—that part is happy my father is free.” At the same time, she realizes that no one is her father’s equal when it comes to navigating the marshland, and that it’s up to her to catch him.

As Helena hunts her father to return him to prison, gradually, she realizes that as much as he dominated her when she was small, she always had power over him. Without her, he would still be a man, but he wouldn’t be a father. Like all fathers and daughters, Helena and her father can never escape each other.

—

Karen Dionne is the author of The Marsh King’s Daughter, a dark psychological suspense novel set in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula wilderness coming June 13, 2017 from G.P. Putnam’s Sons in the U.S. and Canada, and 20 other countries.

She is cofounder of the online writers community Backspace, and organizes the Salt Cay Writers Retreat held every other year on a private island in the Bahamas. She is a member of the International Thriller Writers, where she served on the board of directors as Vice President, Technology.

Karen’s short fiction has appeared in Bathtub Gin, The Adirondack Review, Futures Mysterious Anthology Magazine, and Thought Magazine, as well as First Thrills: High-Octane Stories from the Hottest Thriller Authors, an anthology of short stories from bestselling and emerging authors edited by Lee Child.

Karen has written about the publishing industry from an author’s perspective for AOL’s DailyFinance, and blogs at The Huffington Post. Other articles and essays have been published in Writer’s Digest Magazine, RT Book Reviews, Guide to Literary Agents, and Handbook of Novel Writing (Writers Digest Books).

Karen has been honored by the Michigan Humanities Council as a Humanities Scholar for her body of work as an author, writer, and as co-founder of Backspace. She enjoys nature photography and lives with her husband in Detroit’s northern suburbs.

Find out more about her on her website http://www.karen-dionne.com/

Follow her on Twitter @KarenDionne

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing