Writing a Novel on Ballet in Pre-Revolutionary Russia

kturnerwriting@gmail.com

Historical fiction allows us to time travel; we step into the past with a sense of wonder and awe, and the famous names become more than a list of people we learned about in textbooks and school history classes. They become people.

The idea for my historical fiction novel was sparked by a single sentence. Joan Acocella, in her introduction to The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky, wrote: ‘In those days in Russia there was a heavy sexual trade in ballet dancers.’ I have always known a lot about ballet. I trained to be a ballerina.

Growing up in a small town I knew I couldn’t compete with the training and experience of city girls, so I decided to give myself an edge by knowing more about ballet – the theory, the history, the people who influenced it – than anyone else. Later, History of Dance was a required subject of my associate degree in dance. Yet here was a fact I’d never come across. One which, upon further research, included names I’d previously thought I knew everything about: Anna Pavlova, Nijinsky himself. Even the imperial Romanov family.

In that sentence I knew I’d found the beginnings of a book. And the beginnings of a very long research process to do the subject matter justice.

It’s not easy, or sometimes even advisable, to write about a country and culture you don’t belong to. I started where we all do: by turning to books and the internet. The first thing was to read generally about the time and subject matter, to understand if this one sentence could really lend itself to an entire book. As I read, I wrote down points of interest – both for further research, and for creating the outline of what would become The Last Days of the Romanov Dancers. Once I felt as though I had a story worth telling, it was time to find answers to harder questions. What is unique to the Russian experience? How do they think, feel, face everyday topics? What challenges were specific to the country and era? How do I differentiate cliché from tradition?

For me the most important part of my research process was maintaining respect for the other culture, and never assuming anything. When you assume something about a culture, even the smallest details, you run into trouble. For instance, if I’d set my book only a few years later, the Christmas scene being on December 25 would immediately stand out to Russian readers as inauthentic or a mistake. For, after the revolution, Russia changed from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar to be in line with the western world, but many Russians didn’t like to change their Christmas traditions. So Christmas was, and still often is, celebrated on January 7. These were the details which became the most important for me to research – the tiny things one might assume from their own experiences, but which turn out to be uniquely different.

It can sound restrictive, but I found research and historical authenticity opened a whole new world of possibilities for my story. Learning the facts I needed to work within gave my creativity focus and the story shape. Of course, there were challenges with it too. I’d sometimes find myself asking, ‘How do I do this when history tells me that would have happened instead?’ These moments often resulted in the best writing. Instead of going with whatever popped into my head first, I was forced to find inventive ways to realistically allow my characters to move and act in the ways I wanted.

As part of my research I was lucky enough to travel to Russia. There, I watched ballets on centuries-old stages, visited the homes of the real-life people who populate my book, and saw the final resting place of the executed Romanovs – the family whose patronage of and belief in the arts shaped ballet into what it is today. (Even my own dance training can be traced back to the dancers of the Romanovs’ Imperial Russian Ballet.)

Being there was like stepping into the pages of the book I wanted to write. I’ll never forget the tone of voice the Russian people had when speaking to me about the murdered Romanov family: a deep yet quiet and resigned sadness, with just a hint of unanswered questions. This experience helped shape the tone of my book. There is a resounding sense of loss to it; not just the individual losses of life, but the loss of a place and time that would never quite exist in the same way again.

Through a combination of lived experience and theoretical research I was able to build a world in which readers can temporarily live the rare life of one of the Romanov ballet dancers. It’s not going to be perfect, for nothing ever is, and I take full ownership of any mistakes that did manage to slip through. But what I hope is that I have been able to humanise a moment in history.

The Last Days of the Romanov Dancers taught me so much. My journey from a small idea to a finished book opened me up to a world of poverty, influence, class divides, societal constraints, love in unexpected places, loss and redemption. It brought me into contact with people who opened their arms and welcomed me into their culture. Writing it was an experience I would not change for the world.

—

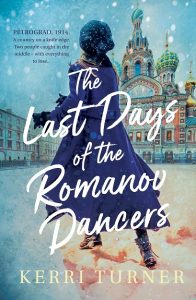

The Last Days Of The Romanov Dancers

Petrograd, 1914. A country on a knife edge. The story of two people caught in the middle – with everything to lose… A stunning debut from a talented new Australian voice in historical fiction.

Petrograd, 1914. A country on a knife edge. The story of two people caught in the middle – with everything to lose… A stunning debut from a talented new Australian voice in historical fiction.

Valentina Yershova’s position in the Romanovs’ Imperial Russian Ballet is the only thing that keeps her from the clutches of poverty. With implacable determination, she has clawed her way through the ranks, relying not only on her talent but her alliances with influential men that grant them her body, but never her heart. Then Luka Zhirkov – the gifted son of a factory worker – joins the company, and suddenly everything she has built is put at risk.For Luka, being accepted into the company fulfils a lifelong dream. But in the eyes of his proletariat father, it makes him a traitor. As civil war tightens its grip and the country starves, Luka is torn between his growing connection to Valentina and his guilt for their lavish way of life.

For the Imperial Russian Ballet has become the ultimate symbol of Romanov indulgence, and soon the lovers are forced to choose: their country, their art or each other…

A powerful novel of revolution, passion and just how much two people will sacrifice…

“A wonderful debut from author, Kerri Turner … Through her own work as a dancer, and thorough historical research, Turner has created figures that literally dance off the page. Like the influence of the ballet company itself, the characters will stay with you long after you have finished reading it.” – Caroline Beecham, author of Eleanor’s Secret and Maggie’s Kitchen

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing