Broth from the Cauldron: A Wisdom Journey through Everyday Magic: an Excerpt

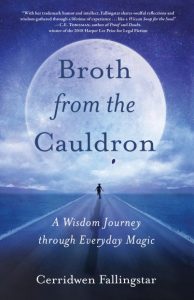

How does a Republican girl, raised in an agnostic scientific household, become a Pagan Priestess? Broth from the Cauldron: A Wisdom Journey Through Everyday Magic (May 12, She Writes Press) by Cerridwen Fallingstar shares profound insight in this charming and wholly unique memoir of meditations on topics such as perception, fear, anger, trauma, healing, magic and gratitude.

How does a Republican girl, raised in an agnostic scientific household, become a Pagan Priestess? Broth from the Cauldron: A Wisdom Journey Through Everyday Magic (May 12, She Writes Press) by Cerridwen Fallingstar shares profound insight in this charming and wholly unique memoir of meditations on topics such as perception, fear, anger, trauma, healing, magic and gratitude.

In this soulful collection of “teaching stories”, Fallingstar recounts her earliest memories of reincarnation, her parents’ denial of the powerful intuition and visions they all shared, and the injustices and abuse which inspired her “career as a hippie, war protester, rebel, feminist, and bisexual Witch.” With a refreshing sense of humor, Fallingstar offers a portrait of a culture growing from denial to awareness – a pertinent reflection for our time.

“Fallingstar’s writing is conversational and welcoming, encouraging introspection. Her entertaining stories illustrate deeper truths about how others should be treated, regarding the wisdom of animals, and about the power of intuition.” ―Foreword/Clarion Reviews

We are delighted to feature this excerpt!

Excerpted from Broth from the Cauldron: A Wisdom Journey through Everyday Magic by Cerridwen Fallingstar. © 2020 by Cerridwen Fallingstar. She Writes Press, a division of SparkPoint Studio, LLC.

—

In the Stranger’s Guise

And the lark sang, and in her sweet voice, she sang, “Often, often, often, comes Christ in the stranger’s guise. Often, often, often, comes Christ in the stranger’s guise.”

—Traditional Celtic

The octopus flirtatiously extended one of her arms, then coiled it back into a perfect spiral. “Ooh, you’re so beautiful,” Morning Glory and I cooed to it through the glass.

Shyly at first, then with increasing confidence, the octopus fluttered the ends of three of her legs, her tentacles trembling like a belly dancer’s zills. Her body billowed like a sail as she pirouetted, iridescent with happiness. She changed shape and form, fluid as fire in the water; she fluttered her tentacles like kisses against the glass. She pressed her large, dark eye against the glass, gazing at us while she stretched her legs to their fullest extension.

“Oh, gross!” the boy shouted as he ran up to us. His mother was close behind. “Oh!” she shuddered. “That is so disgusting!”

Immediately the octopus disengaged from the window and huddled in a ball as far from us as possible, her flesh white as paper, the color that indicates an octopus is in distress.

“It’s not ugly, it’s beautiful,” we remonstrated the young family.

“Are you kidding? That thing is totally repulsive,” the woman insisted.

“That’s just your assumptions that make you say that. Try looking at it with fresh eyes,” I coaxed.

“They’re very intelligent and very sensitive. When you call it ugly, it hurts her feelings. Think nice thoughts and maybe she’ll come out and dance for us again,” Morning Glory added.

“Come on, beauty,” she crooned, rubbing the tips of her fingers gently against the glass.

Tentatively the octopus extended a single arm. As we continued to pour love through the aquarium glass, she slowly unfurled and became a lovely soft shade of green. Once again she danced a graceful, boneless ballet.

“You’re right,” the woman said in a bewildered tone. “It really is beautiful.”

“Yeah, cool,” her son agreed.

Morning Glory and I stayed with that octopus at the Scripps Institute all day. Each time other visitors came up to the glass, they would loudly declare their disgust. Each time we begged them to look beyond their fear and loathing to actually see the creature in front of them. Each time, they were surprised at how lovely the octopus was when viewed without prejudice.

Jacques Cousteau referred to octopi as “a soft intelligence.” His crew spent several weeks diving to a huge octopus colony. They fed the octopi, who grew to expect their visits. Then they started presenting the octopi with their favorite food, lobster, in an enclosed bottle. Within seconds, the octopi would figure out how to open the bottle, whether by removing a cork or twisting a sealed lid. Gradually the divers realized that no matter what time of day or night they dove, no matter how soundlessly they approached, the octopi would have emerged from their shelters and were waiting for them. They appeared to be not just problem solving, but telepathic. In captivity, octopi do not live long. The humans who visit them spew hatred at them all day. Soon the octopi no longer dance, but huddle, brick red with anger, or pale with grief, in a sullen knot far from the glass. Soon, they perish.

Because our culture is xenophobic, afraid of what is strange, afraid of the “other,” we assume that this is a normal human characteristic. But most cultures have a tradition of the stranger as being sacred. Hospitality and protection offered to any unknown person approaching one’s house are still practiced in many of the world’s more traditional cultures. In a polytheistic, pantheistic society, the Gods are ubiquitous; shape-shifting, they can assume any form. Robert Heinlein once observed that an armed society is a polite society. A polytheistic society is also a polite society; it is never a good idea to offend the Gods, and since the Gods might inhabit any being at any time, polite consideration of all creatures becomes a way of life.

In 1803, the Lewis and Clark expedition set off to cross the North American continent to the Pacific. One of the team members was York, Clark’s slave. In most of the Indian villages they encountered, the inhabitants had encountered white trappers, but had never seen a black man. They were electrified to discover a man with black skin, with hair as curly as their sacred buffalos’. In each village where they stopped, tribesmen asked York to sleep with their wives so their village could have some people who looked like him. Two years later, when the expedition returned across the continent, the Indian women who had successfully conceived during these visits emerged from their homes triumphantly holding their little curly-haired babies above their heads. Did they think York had powers? Did they imagine he might be a buffalo deity? Or did they just think he was cute?

We can’t know what they thought, but we can deduce from their behavior that they were not afraid of his differentness, but rather, found it valuable and attractive.

The Cherokee people have a very sophisticated set of psychological and sexual teachings called the Chuluaqui-Quodoushka. One of the teachings of this tradition is that different beings have different orende levels. Orende could be translated as energy, or vibration. A rock, typically, has an orende level of one, a plant would likely have an orende level of two. An average human might have an orende level of four, five, or six. (Higher orende is not seen as better or worse, simply as different.) A powerful shaman or a bodhi- sattva might have an orende level of eight or nine. Humans are complicated. A person might have a physical orende level of seven, a spiritual level of four, an emotional expression of five, an intellectual marker of six, leading to an overall orende level of five. When one person has an orende capacity two or more levels above or below another, repulsion is the natural response. The Quodoushka counsels that curiosity can bridge that gap. By stopping ourselves in mid-recoil, and wondering how the other person thinks and feels and organizes reality, we can become interested rather than judging and rejecting.

The Cherokee people have a very sophisticated set of psychological and sexual teachings called the Chuluaqui-Quodoushka. One of the teachings of this tradition is that different beings have different orende levels. Orende could be translated as energy, or vibration. A rock, typically, has an orende level of one, a plant would likely have an orende level of two. An average human might have an orende level of four, five, or six. (Higher orende is not seen as better or worse, simply as different.) A powerful shaman or a bodhi- sattva might have an orende level of eight or nine. Humans are complicated. A person might have a physical orende level of seven, a spiritual level of four, an emotional expression of five, an intellectual marker of six, leading to an overall orende level of five. When one person has an orende capacity two or more levels above or below another, repulsion is the natural response. The Quodoushka counsels that curiosity can bridge that gap. By stopping ourselves in mid-recoil, and wondering how the other person thinks and feels and organizes reality, we can become interested rather than judging and rejecting.

An octopus can squeeze into any space big enough for its eye. When we use the eyes of the heart, we can do the same.

—

Cerridwen Fallingstar is a shamanic Witch who has taught classes in magic and ritual for over thirty years. She gives lectures tying together psychology, spirituality, history, contemporary issues, and politics in an entertaining, enlightening, and humorous format. She is the author of Broth from the Cauldron: A Wisdom Journey through Everyday Magic as well as three historical novels based on her past lives: The Heart of the Fire, White as Bone, Red as Blood: The Fox Sorceress, and White as Bone, Red as Blood: The Storm God. She lives in Marin County, California.

Category: On Writing

Thanks Emerald! Hope you continue to enjoy the Broth.

Blessings,

Cerridwen

I have already ordered and received this book (as a result of reading one of your previous pieces on this site) but have not started reading it yet. This excerpt makes me look forward even more to doing so! A simply gorgeous account of such beautiful recognitions. Thank you.