A Confederacy of Authors

L B Gschwandtner

A few years back, I read an article on HuffPo titled Sticks & Stones: The Changing Politics of the Self-Publishing by Terri Giuliano. She made the case that a) self publishing or, as it’s now known Indie Pubbing, is growing fast, b) some authors published by traditional houses resent this, c) sales for ebooks are climbing, d) sales of paperback books are declining, and e) a bunch of other points too numerous to detail here but they’re all in the original article.

A few years back, I read an article on HuffPo titled Sticks & Stones: The Changing Politics of the Self-Publishing by Terri Giuliano. She made the case that a) self publishing or, as it’s now known Indie Pubbing, is growing fast, b) some authors published by traditional houses resent this, c) sales for ebooks are climbing, d) sales of paperback books are declining, and e) a bunch of other points too numerous to detail here but they’re all in the original article.

While the article is well researched and full of juicy nuggets, it climbs like ivy all over the edifice that is publishing, making so many cases that it’s a bit like trying to identify one speck of dust in a maelstrom. But, among all the points tossed out for consideration, one struck me particularly and I’ll focus he

In the old days, determined authors turned to self-publishing—or vanity presses, as they were called—as a last resort. Serious authors, concerned about being black-balled, dared not self-publish. As a result, talented authors like John Kennedy Toole, whose posthumously published masterpiece, “A Confederacy of Dunces,” won a Pulitzer Prize (1981), went to their grave believing their work did not measure up.

Now, I do not know what fast track the writer of this article had to author John Kennedy Toole’s conscious, unconscious, or subconscious mind but to state that he went to his grave believing his work did not measure up seems a bit overstated and presumptuous. Not to mention, since she uses the pronoun “their,” other [unnamed] writers who, similarly discouraged by the lack of a publishing contract in New York, did themselves in.

The story of Toole’s many rejections by the publishing world are legendary. The story of his mother’s continued efforts to get his one book, A Confederacy Of Dunces, published after his death are also legendary. That’s what we know. We do not know what was in his mind before his death or why he succumbed to such despair that he gained an enormous amount of weight and consequently took his own life.

Did Hemingway go to his grave believing his work just did not measure up? Or did Sylvia Plath? How about Virginia Woolf, Jack London, Hunter S. Thompson, Jerzy Kosinski, Anne Sexton, and many others, all of whom had publishers solidly in their corners. They also had public adulation and big bucks in their pockets. Yet they still went to their graves by their own hands.

Does this tell us something? Is there a clue lurking in these tales of despair? Is the writer of this article trying to say – in some veiled way – that not getting a publishing deal and recognition by some agent or editor in New York can kill a writer? OMG, hopes dashed, nothing left to live for, no agent likes my work.

Reading between the lines of Toole’s book, and taking a lot for granted in making certain assumptions, one could – let me rephrase – I could venture to guess that John Kennedy Toole, much like his protagonist, Ignatius J. Reilly, felt very much the post adolescent outcast. Or at least he identified with that feeling enough to write about it in excruciating detail matched only, perhaps, by Holden Caulfield’s adolescent angst.

Ask any psychiatrist and you’ll find that adolescent brains are not fully formed and what’s there is kinda mushy (not especially technically accurate but apt I think). Anyone who’s observed a teen can see it. It’s not a great leap to imagine that Toole could have come out of his own adolescence severely depressed

A reading of William Styron’s Darkness Visible should make clear to anyone what depression does to a person’s brain function. Basically depression shuts off all but the worst feelings and makes life so unbearable that death seems like an appealing alternative. It is a mental process with the most severe physical manifestations including lethargy, sleeplessness, weight changes, drug or alcohol abuse, and others. But this has nothing to do with publishing houses.

So, while the article provides many fascinating and salient facts about what’s happening in publishing today, and shows readers that alternatives to a closed market are always better than a market that is controlled at the top by a select few, it also makes some assumptions that are uninformed at best and destructive at worst.

The next time a writer feels really low, he or she should look not toward New York but much closer to home (even if home is New York). And get some help. Because it’s out there. And being a writer can be a lonely, self absorbing occupation that does not lend itself to simple self repair.

It seems to me, at this point in our collective culture as writers, there are two kinds of authors, whether self published or traditionally published.

The first is the group of writers who consider writing a profession like any other. Nuts and bolts, write because you have to make a living, satisfy a market niche, promote the hell out of your work, and deposit your checks somewhere safe because the work is too hard to risk the rewards on a hot stock.

The second is the group – Like Toole – who have something very personal to say, about themselves and the culture that influences and informs them. You won’t find them writing about vampires or shape shifters. You won’t find sex scenes every ten pages in their books. You won’t be inundated in their books by cutesy witches who fall in love with handsome hunks or lady detectives who wear provocative skirts and kick back with the boys in the squad room.

Sometimes the two groups overlap – Jack London comes to mind. So even though some writers, based solely on their writing, are more angst ridden than others, even the nuts and bolts genre writers can be depressed. But depression and suicide are not limited to writers. And I suspect that John Kennedy Toole’s problems pre-dated any rejections by New York publishing houses. It’s a sad fact that he was gone from our sight so early. It’s a sad fact that so many other writers took the same path. It’s a sad fact that the world can be a cruel and unfeeling place. Writing requires resilience. Emotional and psychological resilience. While writers are developing their skill set, they must keep this in mind and not allow the world to tell them who or what they are and how to value themselves. Because the sad fact is that the world just does not give a damn. So we, as writers must.

—

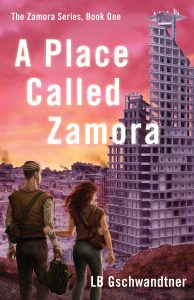

LB Gschwandtner has attended numerous fiction-writing workshops―the Iowa Writers Workshop and others―studied with Fred Leebron, Bob Bausch, Richard Bausch, Lary Bloom, Joyce Maynard, Sue Levine, and Wally Lamb, and published five adult novels, one middle-grade novel, and one collection of quirky short stories. She began her professional career as an artist, became a magazine editor in 1980, and began writing fiction in 1986. She’s won awards in literary contests and independent publishing contests, and been published in literary digests and magazines. A Place Called Zamora is her eighth book.

A PLACE CALLED ZAMORA

Niko and El are trapped in a politically corrupt dystopian city where brutality rules. After winning a cynical race where only one rider can survive, Niko tosses aside his chance to join the city’s corrupt inner circle by choosing lovely, innocent El as his prize—thus upsetting the ruling order and placing them both in mortal danger. With the Regime hunting them and the children of the city fomenting a guerrilla revolt, the two attempt a daring escape to the possibly mythical utopia, Zamora. But as events unfold, the stirrings of love El once felt for Niko begin to morph into mistrust and fear. If they reach Zamora, will Niko ever claim his secret birthright? And what will the future hold if he loses El’s love?

Niko and El are trapped in a politically corrupt dystopian city where brutality rules. After winning a cynical race where only one rider can survive, Niko tosses aside his chance to join the city’s corrupt inner circle by choosing lovely, innocent El as his prize—thus upsetting the ruling order and placing them both in mortal danger. With the Regime hunting them and the children of the city fomenting a guerrilla revolt, the two attempt a daring escape to the possibly mythical utopia, Zamora. But as events unfold, the stirrings of love El once felt for Niko begin to morph into mistrust and fear. If they reach Zamora, will Niko ever claim his secret birthright? And what will the future hold if he loses El’s love?

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: On Writing