Writing MUSE: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind art History’s Masterpieces

I remember the day vividly well. Due to Covid, we were all in a strict and first imposed lockdown in London. I was working in the upstairs bedroom when I saw the new email pop into my inbox. It came bearing neatly typed bad news from my publisher: with much regret, they were going to have to put my book on indefinite hold as their team were being furloughed due to the pandemic.

I remember the day vividly well. Due to Covid, we were all in a strict and first imposed lockdown in London. I was working in the upstairs bedroom when I saw the new email pop into my inbox. It came bearing neatly typed bad news from my publisher: with much regret, they were going to have to put my book on indefinite hold as their team were being furloughed due to the pandemic.

I had been just days away from finalising, and signing, the contract for my first book with them. To have this deal taken away now, because of forces beyond my control, felt deeply unfair. I cried into my computer, inside that claustrophobic room.

It had taken me many months to get to this stage; I had contacted no less than 30 literary agents – only 1 replied with their politely-worded rejection. I also sent submissions to over 40 different publishers without success. Only silence.

“J. K. Rowling sent her manuscript to 12 publishers” a supportive friend told me during the process of write, review and submit. “Just 12? That’s nothing!” I told her.

Determined to get published, I had also decided to go part-time in my day job to commit to this goal. On one particularly tedious afternoon I recall being cornered in the bathroom by a manager:

“I hear you’re going part-time. You know, once you reduce your days, you can’t come back full time”.

She swung out into the corridor without giving me the chance to reply.

But also ringing in my ears was some golden advice from a professional scriptwriter friend of mine:

“If you want to be a writer, it’s simple. You have to commit to it. Only you really care if you get published”.

I knew he was right. I would have to say no to events and gallery openings, and to bosses who didn’t want my focus elsewhere.

“NO” I scribbled onto a pink post-it note, sticking it onto the case of my old laptop.

I saw that note now, still clinging on.

I’ll never forget that day. Not only did it prove to me just how much I wanted to get published. It was also the greatest rejection I ever received.

That small publisher didn’t get in touch again for a year. But in the meantime, something big happened. Or rather, I made something big happen.

A few weeks after learning that the book – which would tell the story of Birmingham’s art history – wasn’t going to leave my laptop anytime soon, I reached out to a publishing contact.

I told her what had happened, and she gave me some beautifully frank advice:

“Why don’t you think of another idea? For a larger audience? And not a coffee table book, as they are expensive for publishers to produce”.

She sent me some examples of paperback style art books, including ‘Girl in a Green Gown: The History and Mystery of the Arnolfini Portrait’ by Carola Hicks.

I’d just written 2 features on the true stories, and real-life individuals, behind famous artworks. Who is the Mona Lisa? Or Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring? What about Picasso’s Weeping Woman? I’d been researching, and writing about, this very topic.

I’d also been reflecting on the idea of the muse, as one editor had asked me NOT to use that term. It’s come to carry pejorative and sexist connotations, of a young female model posing naked for an older male artist. But I had also begun to think about how unfair, and untrue, this stereotype was.

And so, I wrote. And wrote.

My publishing contact had kindly offered to look at future proposals and within 3 weeks I had the beginnings of a new one. Playing to my strengths, as a feminist and modern art historian, I wrote a sample chapter on Dora Maar, who has been immortalised in the image of Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’.

This portrait is often read – in patriarchal narratives that frame women as mere romantic partners – as an inflection of her troubled relationship, and the abusive way in which Picasso treated her. But, if you look closely, you can see black war planes in her eyes, proving Maar’s political convictions, which had a profound impact on Picasso.

In her darkroom, the successful Surrealist photographer Maar taught Picasso complex photographic processes. Outside of it, she also indoctrinated the painter in her ultra-Left-wing politics, which infused not only Picasso’s portraits of her, but the epic anti-war mural, ‘Guernica’ (1937). In fact, it was Maar who found Picasso a site large enough for this huge protest painting — it was the former headquarters of her radical political group, Contre Attaque.

Inside the space, Maar photographed Picasso making the mural and helped him with sections of painting it. Leaving his bright palette behind, he created ‘Guernica’ in black and white, influenced by Maar’s photography. There is even a darkroom spotlight in the picture, beneath which appears, for the first time, Picasso’s famous ‘Weeping Woman’

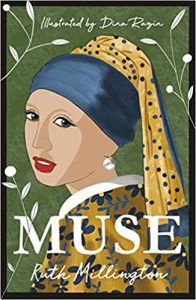

This would be a chapter in my next manuscript, which I had tentatively, but ambitiously, titled in capitals, ‘MUSE’.

Just a few hours after emailing over the proposal, my contact emailed back. “Ruth, this is wonderful!”.

She loved the idea of a book focused on the art world’s most famous muses, with that word centre-stage. I had argued, in my pitch, that it was time to reclaim the term for patriarchal narratives and prove that muses were active agents in art history.

From here, I worked on a formal proposal which I sent to Square Peg Books, an imprint at Penguin Random House. They require over 50 pages of an introduction, sample chapters, a conclusion, synopsis and author biography. Who would be my audience? How would I market it? Which competitor titles were there? It took me 6 months to research 30+ muses that would be included, answer these questions, and shape a compelling proposal. I often doubted myself: was this unpaid labour going to pay off?

It was on Wednesday October 21st, 2020, just after 11am, that I opened the email from my editor-to-be at Square Peg Books:

“You have no idea how delighted I am to finally bring you this offer letter. I am so excited for Muse to be out in the world and for Square Peg to be a home for your book. Thank you endlessly for your patience over the past few months and relentless commitment to reshaping this to make it the brilliant work it is. I am thrilled to be offering you this and I hope to continue you to grow you as a writer beyond this book and for this to be the start of a brilliant career for you.”

From that first no, I now had my yes, and not just one yes but many. Since opening that offer, I have since sold the rights to Muse across the world, from the US to Ukraine and Brazil.

Muse was meant to be my first book.

—

About the Author: Ruth Millington is an art historian, critic, and author specializing in modern and contemporary art. She has written for various publications, including The i newspaper, Sunday Times, Telegraph, Daily Mail, Sorbet Magazine and BBC Online. She has been featured as an art expert on TV and radio, including BBC Breakfast, Sky Arts and ITV News.

Muse: Uncovering the hidden figures behind art history’s masterpieces

Meet the unexpected, overlooked and forgotten models of art history.

Who was Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’?

Who was Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’?

Why was Grace Jones covered in graffiti?

How did Francis Bacon meet the burglar who became his muse?

The perception of the muse is that of a passive, powerless model, at the mercy of an influential and older artist. But is this trope a romanticised myth? Far from posing silently, muses have brought emotional support, intellectual energy, career-changing creativity and practical help to artists.

Muse tells the true stories of the incredible muses who have inspired art history’s masterpieces. From Leonardo da Vinci’s studio to the covers of Vogue, art historian, critic and writer Ruth Millington uncovers the remarkable role of muses in some of art history’s most well-known and significant works. Delving into the real-life relationships that models have held with the artists who immortalised them, it will expose the influential and active part they have played and deconstruct reductive stereotypes, reframing the muse as a momentous and empowered agent of art history.

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips