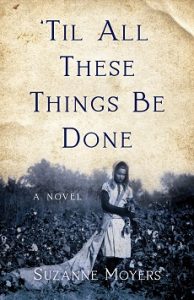

Authors Interviewing Characters: Suzanne Moyers

About ‘Til All These Things Be Done

An…intensely gratifying page turner…Love, longing, and the hard persistence of hope shine in this debut novel. –Elizabeth Crook, author of Monday, Monday and The Which Way Tree

Set within the unique but troubled history of ‘blacklands,’ Texas, during an earlier era of pandemic and social upheaval, ‘Til All These Things Be Done will grip your heart and never let go.

Even as dementia steals other memories, eighty-three-year-old Leola Rideout can’t forget her father’s disappearance in 1919. Now, as Papa appears in haunting visions, she relives the circumstances of that loss like they’re happening anew: the terrible accident that steals Papa’s livelihood, forcing him to seek work in faraway Houston; an old family scandal that still wounds; and Leola’s growing unease with her cruelly bigoted society.

After Papa vanishes, Leola struggles to keep her family—and dreams—alive, ever hopeful of his return. That hope fades when she exposes a dark crime, jeopardizing a tantalizing clue to Papa’s whereabouts. It’s a choice that echoes into the future, as new details of her father’s whereabouts suggest such painful betrayal, she vows to forget him forever. Only in old age, with those ghostly visions of Papa growing more urgent, does Leola fully confront her deepest loss, leading to a remarkable family discovery that could bring the peace she seeks.

Suzanne Moyers interviews her protagonist, Leola Rideout, as an elderly woman.

SM: Thanks for taking the time to speak with me today.

LR: No trouble, dear. What would I be doin’ otherwise but staring out the window, recollecting days of yore?

SM: In fact, I was hoping to ask you a few questions about your past, especially when you were a young woman in rural Texas. I know it was a difficult time…

LR: …because Papa left then, yes. But I have good memories too.

SM: Any in particular you can share?

LR: I did enjoy automobile outings with my dear chum, Mary Shipley. (A brief sadness falls over her face, and she pauses.) And stealing away with my sweetheart, Joe Belfigli, to spend some quality time together. (Laughs.) And then there were the feasts we’d enjoy after onerous chores like goose plucking or hog killing. My great-aunt Malvina made a larrupin’ good mayhaw trifle. (We both smack our lips.)

SM: My grandparents grew up in similar circumstances so I know it was far from fun and games.

LR: Oh, yes. The chores were endless: doing laundry, shelling corn, sweeping our limestone yard. And after Papa lost his job, I picked cotton to earn wages. It was commonplace then, for young people to support their families.

SM: One of my grandmothers picked cotton. She liked the pay but not the hard labor.

LR: Sure was hard, all that stooping and reaching, the broiling sun. Snakes too! (Glances down as if checking between cotton rows.) At least I had hopes of winning a college scholarship, escaping a lifetime of such labor—which wasn’t true for others. Take that harridan, Opal Suggs. For all she was a thorn in my side, I did pity the girl at times.

SM: Why?

LR: Opal’s family was illiterate, even poorer than mine, not a patch of dirt nor nothing much else to their names. Low-lifers, people called them. White trash. Papa disapproved of such terms, saying the only thing separating them from us was a too-long stretch of bad luck. (Shakes her head.) How right he was about that!

At least the Suggs, being white, had more opportunity than the Black laborers. Wasn’t just kids out there pickin’, either, but young men in their prime, doing the rare job Black folks were allowed to do. ‘Course, they often got cheated at weighing time and heaven forbid they complain about it!

SM: It was a time of vicious racial oppression, not just in Texas but other parts of the country. Although you were white, it must’ve had an effect on you.

LR: As a child, I didn’t think much of it. Like when a Black person stepped off the sidewalk to let us pass, or an old man got called Boy and then had to call me Miss in turn. We were taught such customs by example and repetition, along with our ABCs. But that summer I turned 16, things changed—in the world as in my heart.

SM: How so?

LR: I read stories in the newspapers about Black veterans home from WWI, agitating for freedoms long overdue, and whites answering with the worst kind of savagery…

SM: Did you ever witness that violence firsthand?

LR: I hadn’t at that point but it didn’t take physical brutality to open my eyes. Was something else, an everyday act I’d seen committed thousands of times before.

SM: Can you talk more about that?

LR: I was at the dry goods store when our family friend, George Gumbs— himself a soldier of the Great War—got treated like he was invisible or worse. George spoke up against it too! I’d never seen that before. It made me realize how wrong everything was. (She stares into her lap.) I’m afraid didn’t do much about it until much later on.

SM: You were poor, young, and female. The Klan was active in those days, targeting Blacks worse than ever but others too, including white folks who protested such treatment.

LR: Maybe. I’d certainly had my own experience with those Kluxxers, when they abused Joe for being Catholic and the son of an immigrant. My own neighbors too, spouting Do Unto Others, then acting so cruel…Left a mark on my soul sure as the influenza left a scar on my lungs.

SM: Speaking of which, we’ve had our own pandemic of late, nearly a century after the one you survived.

LR: Another influenza plague?

SM: It was a different virus, COVID, but just as contagious and deadly. Living through it gave me a better understanding of what you experienced. I’m sure the influenza was a real obstacle in finding your father.

LR: Didn’t help, what with the railroads and telegraph offices shut down for weeks. All those rounds of quarantine. Then Mama and me got sick. Afterwards, I was too busy caring for my sisters to conduct a proper search.

SM: Did anyone try to help you find him?

LR: Mrs. Valchar, our guardian angel in Waxahachie. Was her sleuthing, turned up the first real clues to Papa’s fate.

SM: But she didn’t learn everything, right?

LR: No. The rest I discovered for myself over the years. Nearly broke me. (Her face quickly brightens.) But recently I got better news, something that eased my heart. (She winks.) For that, I had help from Papa himself.

SM (looking confused): But you’re almost ninety years old. Papa must’ve passed a long time ago…

LR: Grief denied can raise the dead right up, dear, don’t you know? ‘Course when I told everyone he’d returned, no one believed it. Said it was my failing mind, playing tricks on me. (She scoffs.) Guess I showed them…

SM (gulping): Your father was here? Like, his spirit?

LR: Never did give much credence to such supernatural nonsense but the fact is, life’s full of things we can’t understand but know in our hearts to be true.

SM (checking over shoulder): So does Papa, uh, still haunt you?

LR: Not so much in his ghostly form, though he does still visit me in a way. Quite often, in fact.

SM: I’d ask you to explain except I’m guessing it would ruin the ending to a certain, ahem, novel.

LR: You’re right. If folks want to learn how the story comes out, they ought read it themselves. (Checks her watch.) And speaking of stories, my soap’s on soon. Anything else you’d like to know?

SM: What helped you survive so much adversity?

LR: Forgiveness. If I hadn’t forgiven those I love—and myself—countless times, my heart would’ve turned to stone and I’d be completely alone. Not to say you should put up with just any treatment, but understanding others keeps the hurts from eating you alive.

SM: Good advice, and the perfect note to end our interview on. Thank you again for doing this.

LR: Pleasure was all mine, dear. (She leans forward, whispering.) Papa’s too.

—

Suzanne Moyers, a former teacher, spent more than 20 years as an editor and writer for the education press. Suzanne is an avid history buff who, when she isn’t writing, enjoys metal detecting, mudlarking, and volunteering for archeological digs. The mom of two amazing young adults, Sara and Jassi, Suzanne lives outside NYC with her husband, Edward, and their perpetual fur toddler, Tuxi. ‘Til All These Things Be Done is her first novel.

Find out more about Suzanne on her website https://suzannemoyers.com/

Twitter https://twitter.com/SuzanneMoyers

‘Til All These Things Be Done

Set against the rich but often troubled history of Blacklands, Texas, during an era of pandemic, scientific discovery, and social upheaval, the novel offers a unique—yet eerily familiar—backdrop to a universal tale of triumphing over loss.

Set against the rich but often troubled history of Blacklands, Texas, during an era of pandemic, scientific discovery, and social upheaval, the novel offers a unique—yet eerily familiar—backdrop to a universal tale of triumphing over loss.

Even as dementia clouds other memories, eighty-three-year-old Leola can’t forget her father’s disappearance when she was sixteen. Now, as Papa appears in haunting visions, Leola relives the circumstances of that loss: the terrible accident that steals Papa’s livelihood, sending the family deeper into poverty; a scandal from Mama’s past that still wounds; and Leola’s growing unease with her brutally bigoted society.

When Papa vanishes while seeking work in Houston and Mama dies in the “boomerang” Influenza outbreak of 1919, Leola and her young sisters are sent to an orphanage, where her exposure of a dark injustice means sacrificing a vital clue to Papa’s whereabouts. That decision echoes into the future, as new details about his disappearance suggest betrayal too painful to contemplate. Only in old age, as her visions of Papa grow more realistic, does Leola confront her long-buried grief, leading to a remarkable family discovery that could offer peace, at last.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing