Navigating The Fact-Fiction Divide

The professor walked through the rows of desks, returning our latest assignments. Mine was a feature piece on a kids’ program in Chicago’s western suburbs. I had been doing well in grad school, finding my voice and feeling confident that I was in the right place. No longer an extracurricular pursuit, journalism would be my career. It would be the thing. I was on my way.

She approached my desk, and I smiled, anticipating the praise I had routinely received. The story landed in front of me. Her fingers tapped the top of the page.

“F,” circled in red pen. “See me.”

I scoured the article for edits but found none that would warrant such a grade. At the end of class, she explained.

“You included an incorrect address. ‘F’ is for factual error.”

I flipped to the spot.

“People are going to read your work because you wrote it, even if it’s about cement,” she said. “If they go to the wrong address, they will never trust you again.”

The lesson has stayed with me for 30 years. I haven’t made a factual error since. I share the experience with my own students and hope it carries the same weight, particularly in the questionable information landscape we now have.

In nonfiction, accuracy is everything. Craft, for journalists covering news, is secondary to getting the facts straight. But what happens when you are a writer, too, as committed to the style, sound and rhythm of the words on the page as much as you are to covering what you see or hear or smell?

I turned to features, which allow for freedom in the narrative form. This sort of storytelling, which examines the how and why, fired up my powers of observation – of place and people. And it naturally led to the essay, which led to the short story, which led to the novel. As a natural observer trained to be even more of one, I’ve found that when writing fiction, I’m most comfortable beginning with something real.

The trick is figuring out how to take what you need from the truth and then break free of it. The most challenging is knowing how to switch back and forth without losing your mind. I must say that there are moments when I am not quite sure if something truly happened or if I fabricated it. It feels as if my characters are having fun confusing me.

In my novel, At the Seams, I used an event from my family’s past to set the characters in motion. A newborn dies in the hospital. No one talks about it, for fear of upsetting the mother. The mystery surrounding the incident, combined with the decision not to address it, seeps through the generations with varying effects. Ultimately, the grandchild investigates, drawing tragic conclusions about how her grandmother suffered in silence.

In real life, I am the grandchild. And, I reported out facts of the baby’s – my uncle’s – death as well as I could. What I couldn’t determine, based on the dissolution or lack of records and absence of primary and secondary sources, I fictionalized.

So, true events can spark an idea, giving you a skeleton for what you need to fill out a story. They can provide an actual sequence of events, setting and cast of characters. Your memory of them, whether you watched them from afar or experienced them personally, is already preserved in pictures in your mind. You describe in words what you see and hear in your head. Often, the intimacy with the scene leads to heightened specificity.

I suppose that different writers veer at different points and in different ways. Some may stick to the structure of the tale but change the characters or their actions. Some may find inspiration from a person they know and give him a new story. Some may remember an image – a dress an aunt wore to a funeral – and take off from there. The methods for fictionalizing reality are really a game of “What if.” What if the aunt really wore the dress, but the widow hated it? What if the funeral was for the aunt’s secret lover? What if he had given her the dress as a gift?

If you’re a nonfiction writer new to fiction, you may have to remind yourself that you can maneuver the facts. You are allowed and encouraged, as odd as that may feel at first. You are creating your own reality, with its own facts. And while you may depart from whatever prompted it, the details contained within that new world need to align. They need to be accurate, or true to the plot, people, time and place that you are inventing. So, if your character walks into a room and the piano is on the left, it should be on the left the next time he enters. Unless, of course, someone secretly replaced it and returned the counterfeit instrument to a different spot. Create consistency with the details that you dream up, or account for lapses in ways that move the story along.

The fact-fiction divide seems pretty clear when it comes to concrete verifiable statements. A car crashed into a pole. The mayor is six feet tall. The grass was cut on a windy day. But the impressions that we draw from these occurrences and conditions muddy the demarcation since they change, depending on who is being impressed. Might one writer feel the wind more harshly? Less? And why choose to include the gusts in the first place? For writers of fiction, though, we need not check our notes or interview recordings or call the National Weather Service. We can manufacture as many tornadoes as we like. How downright wild is that?

—

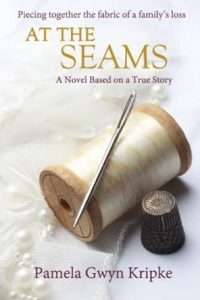

AT THE SEAMS: A NOVEL BASED ON A TRUE STORY

Piecing together the fabric of a family’s loss.

Piecing together the fabric of a family’s loss.

For precocious eight-year-old Kate Nichols, life in suburban New York seems pretty ordinary for the late 1960s. There are ballet classes, pet bunnies and air raid drills, outings to grandparents’ homes and humiliating boys in chino pants. She derives strength from the surgeon father she idolizes and her family’s lineage of dressmakers, all of them sewers who plan and execute with precision.

But Kate’s understanding of her world is shattered when she learns of an uncle who died inexplicably in the hospital just days after his birth. As she navigates adolescence, she must choose whether to crack open the mystery or acquiesce to the family’s established pattern of secrecy and repression. It’s not until she is a single mother that her own feelings of loss trigger a search into the past, revealing a tale of generational trauma, maternal strength and how far we’ll go to protect the people we love.

BUY HERE

Pamela Gwyn Kripke is a journalist and author whose writing has appeared in publications including The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, The Chicago Sun-Times, The Dallas Morning News, The Huffington Post, Slate, Salon, Medium, New York Magazine, Parenting, Redbook, Elle, D Magazine, Creators Syndicate, Gannett Newspapers and McClatchy. Her debut novel, At the Seams (Open Books, 2023), received the Arch Street Press First Chapter Award and was excerpted in Embark and West Trade Review. Pamela’s fiction and creative nonfiction have been published in Folio, The Concrete Desert Review, The Barcelona Review, Brilliant Flash Fiction, Book of Matches, The MacGuffin, Meet Me At 19th, The Woven Tale Press, Underwired, Doubleback Review and Round Table Literary Journal. She holds degrees from Brown University and Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism and was selected to attend the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop for Summer 2022. Pamela has taught journalism at DePaul University and Columbia College in Chicago and has held magazine editorships in New York and Dallas.

Category: How To and Tips