Chapter excerpt from Just Another Epic Love Poem by Parisa Akhbari

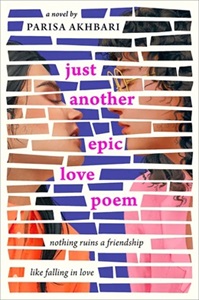

Just Another Epic Love Poem

Best friendship blossoms into something more in this gorgeously written queer literary romance.

Best friendship blossoms into something more in this gorgeously written queer literary romance.

For the past five years, Mitra Esfahani has known two constants: her best friend Bea Ortega and The Book—a dogeared notebook in which she and Bea have been exchanging poems since they were thirteen.

The rules of The Book are simple: No lies, no secrets, and no punctuation. This is a never-ending poem, as epic and everlasting as their friendship. Nothing is too messy or too complex for The Book— not Mitra’s convoluted feelings about her absent mother, or Bea’s heartache over her most recent breakup.

Nothing except the one thing with the power to change their entire friendship: the fact that Mitra is helplessly in love with Bea.

Written in lyrical prose and snippets of poetry, Parisa Akhbari’s debut novel brilliantly captures the euphoria and heartache of a friendship evolving into something more.

Chapter excerpt from Just Another Epic Love Poem by Parisa Akhbari

Bea and I were thirteen when we met, when I transferred into her eighth-grade classroom at Holy Trinity. Bea would fight me on this part, but our friendship—and everything after—began with her pelting me in the back of the head with a wad of paper.

Not that I was a stranger to fielding other people’s spit wads. But my first day had already been off to a miserable start, mainly because of the uniform jumper. It hung in this thick, carpet-like fabric down my body, a pleated headache of red and gold plaid.

This is the first day of the rest of your life, I thought. I looked like a human Christmas tree ornament. And maybe that was the point of Catholic school. How would I know?

We had just moved to Crossroads, the one almost-affordable pocket in the uber-rich city of Bellevue, Washington. I loved our new neighborhood because of its proximity to the Crossroads Shopping Center, home of the only Iranian-owned pizza parlor I had ever heard of. I also loved it because we were surrounded by other brown people. Crossroads felt like a little belly button of familiarity in a giant and strange new city.

But our new school wasn’t in Crossroads. It was in Medina, where everyone had a home tennis court or a pool. And it wasn’t like my old school, which my dad referred to as a “crunchy hippie place” when he found out I spent science class sifting through trash bins to start a composting system. Holy Trinity was a private Catholic school. Which was a weird choice, given that my dad was raised Muslim.

Dad had ushered my eleven-year-old sister, Azar, and me into our new student orientation with a pep talk about how Catholics valued education above all else, and how the teachers would only care that we studied hard. I guess he believed that good grades would shield us—like nobody would notice that we were clearly Iranian American, and didn’t know a thing about Catholicism, because intellect would render us into amorphous orbs of knowledge.

The idea of Catholic school had me convinced I’d be transported into a staging of The Sound of Music, nuns and all. From the brochures, the entire student body of Holy Trinity looked like a beaming sea of von Trapp children. I half expected them to twirl around in their matching jumpers and suit coats and serenade me with “Do-Re-Mi” on my arrival.

Turns out, didn’t happen.

Dad pulled up to the school grounds that first day, sneak-attack kissing my and Azar’s foreheads. “Make it a good day,” he shouted as we slipped out of the car, his accent snagging the attention of some tall boys in blazers. “Make it the best day of your life!”

That’s how Dad said goodbye to us every day since we left Mom—a charge to make the best of crappy times.

Azar and I headed toward the complex of brick buildings, and she immediately broke away from me, flocking toward a gaggle of sixth-grade girls on the lawn. I kept my eyes on the scattered leaves in front of me, not looking up until I reached the arch at the school’s entrance, which was engraved with the words: May God Hold You in the Palm of His Hand.

Each building on campus was named after a Jesuit priest or saint, their faces embossed above the doors so that some old, dead white guy was always scowling down at you upon entry.

Xavier—or Creepy Goatee Dude, as I came to think of him—was cavernous, with a long, dark hallway parting two rows of lockers. The space was packed with students huddling by their respective lockers, every single one of them glued to a phone. The front door thudded behind me, and some of the kids looked up, glaring, before going back to sending their last messages before first period. I didn’t even have my own phone; Azar and I shared my dad’s old Galaxy, which meant she was constantly wrestling it out of my hands so she could play Pet Rescue Saga or video chat the gazillion friends she left behind in Sacramento. I didn’t need my own phone, because I didn’t have anyone to talk to.

As I worked my way toward the classroom, I snuck glances of the Holy Trinity girls. They all looked so shiny and wholesome, like they ate apple pie every night and said prayers and flossed their teeth before bed. Some of them had cross necklaces over their jumpers, and they were all wearing knee-high socks, not the crew-cut ones my dad had picked out for me at the sporting goods store. I’d have to ask my dad for a cross necklace so I could go incognito for as long as humanly possible. I wondered how soon it would be before everyone found out that Azar and I weren’t Catholic.

Behind the door of Ms. Byrne’s eighth-grade classroom, thirty-three sets of eyes zeroed in on me. This was the problem with transferring to a new school in October: Everyone had already established a routine, and here I was, shattering their normalcy with my unfamiliar face and my weird crew-cut socks. I tucked into a desk in the corner of the classroom and stared at the crucifix by the doorway. Jesus, blue-eyed and bleeding, hung stretched out on the cross. Beads of red paint circled the nails in his palms and feet. His head lolled to one side under a crown of thorns. It struck me as pretty graphic for a school where you weren’t allowed to expose your collarbones or wear nail polish.

—

Parisa Akhbari (@authorparisa) is a mental health therapist and writer from Seattle, Washington. Her debut YA novel, Just Another Epic Love Poem, follows two queer best friends in Catholic school as they fall in love through the pages of a never-ending poem they’ve been writing back and forth for five years.When not writing or therapizing, Parisa can be found trying to replicate her grandmother’s drool-worthy Persian recipes, riding ferries around the Puget Sound, and dancing around the kitchen with her wife and dogs. Sign up for her newsletter for a monthly dose of fun arts and culture finds with a spotlight on marginalized creators.

Category: On Writing