Author Interviewing Characters: Author Maggie Anton Interviews Shifra

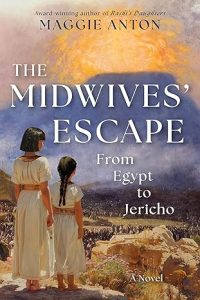

THE MIDWIVES’ ESCAPE

After years of archaeological research and biblical studies, award-winning author Maggie Anton has created a historical novel filled with adventure, warfare, and romance, that is true to both Torah and to history.

After years of archaeological research and biblical studies, award-winning author Maggie Anton has created a historical novel filled with adventure, warfare, and romance, that is true to both Torah and to history.

The Bible contains many extraordinary stories of a sometimes benevolent, sometimes vengeful deity, who guides the Israelites out of slavery, across the Sea of Reeds and through the wilderness to the Promised Land.

Maggie Anton’s THE MIDWIVES ESCAPE: From Egypt to Jericho brings to life this exceptional Biblical journey through vivid descriptions of what daily life was like at this time, epic battlefield scenes and a colorful cast of characters.

An Egyptian mother and daughter, Asenet and Shifra, a midwife and her apprentice, wake up on the morning of the tenth plague to find Asenet’s husband and son, both firstborns, dead. Asenet’s sister Pua, married to an Israelite, urges Asenet’s family to leave Egypt with them, which they reluctantly do, along with Asenet’s wainwright father and his two apprentices. Recognizing that the Hebrew god is more powerful than any of the Egyptians’ gods, other non-Israelites join the exodus, including Hittite and Nubian palace guards. Once hearing and accepting God’s commandments at Mt. Sinai, these two Egyptian midwives join the Israelites on their forty-year journey to The Promised Land where they tend to the wounded, share hardship and adversity, fall in love, and start a new home and a new generation.

With THE MIDWIVES’ ESCAPE, Anton has written an original and stunning recreation of the trials and tribulations on the road to the Promised Land.

Author Interviewing Characters: Author Maggie Anton Interviews Shifra

Maggie: Shifra, thank you for walking and talking with me today; and to your mother Asenet for watching the children while you do. I’d like to start by asking how you ended up with all these sand cats? Don’t you have enough to do with your four children?

Shifra: When Gitlam and I were just children ourselves, we found two orphaned kittens in a cave. They weren’t more than a week or two old, and we couldn’t just let them starve. So we took them back to our tent where Mother took one look at what we carried, then rushed off and returned with two rags and a bowl of goat milk. She twisted the rags, submerged them in the goat milk, and held them up to the kittens’ noses. To our great relief, the kittens took hold and began to suck. I lined an old reed basket with a worn blanket, and that’s where they slept.

A month later, the basket was full of manna, which the kittens eagerly ate when we mixed it with goat milk. Both kittens were female and eventually found mates, which led to litter after litter of more sand kittens. Ultimately, unlike their orphaned mothers who’d been raised by people, these kittens eventually disappeared into the desert. But the females did return when they need to birth their kittens.

Maggie: Why did they stay with you? How did you domesticate them?

Shifra: They stayed with us as long as we fed them goat milk mixed with manna. When they started playing together, although it looked more like fighting to me, they liked to sneak into Grandfather’s woodshop. He tried to discourage them by throwing dowels at them, without using enough force to hurt them. The kittens considered this an excellent game and batted the dowels around relentlessly. When they tired, they would curl up next to me or Gitlam, then let us pet them until they fell asleep.

Maggie: Forgive me if my next question is too private for you to answer.

Shifra: You want to ask about my two husbands? Right?

Maggie: Yes. You three have such an unusual arrangement.

Shifra: I understood that by becoming betrothed to Eshkar, I was also promised to his younger brother Gitlam. That was the Lagash tradition. Their mother also wed brothers and lived with both at the same time. Plenty of men have two wives; why shouldn’t a woman have two husbands? So nine years after my wedding to Eshkar, I married Gitlam. We couldn’t celebrate our nuptials the same way—with an elaborate banquet, musicians and dancing. But we initiated our marriage the same way. My mother, a midwife, had cut my hymen a week before my wedding to Eshkar, so I was healed when we first used the bed together.

Maggie: How do you determine which husband sleeps where, and when? When a man has more than one wife, he must provide a separate tent and maidservant for each wife.

Shifra: I alternate between the brothers, sleeping with Eshkar for two consecutive nights and then spending the next two nights with Gitlam. When I have my menses, I sleep with my sister.

The system works better than I’d expected. The Amalekite copper mine our warriors captured on the way to Mount Sinai has been reopened by the Egyptians and Akkadians previously enslaved there. To protect the workers and mining equipment, Joshua posted a modest regiment of soldiers. Some of them alternated duty, spending two nights at the mines followed by two nights back home in the camp.

Eshkar, now an accomplished swordsman, asked to be one of the guards. So for the two nights I sleep with Gitlam, Eshkar is away at the mining camp. Thus he isn’t confronted with us sleeping together in the tent nearby. Plus, he receives a share of the smelted copper for his efforts. Gitlam, however, has spent years knowing that his brother was sleeping with me. Apparently it didn’t bother him then any more than it does now.

Maggie: But only your family knows that you were Eshkar’s wife in addition to Gitlam’s. How do you decide which of your husbands is the father of which children?

Shifra: I wondered if having two husbands would make me more or less likely to conceive. Not that I can tell which of my children are Eshkar’s and which Gitlam’s. But that is probably just as well. I must admit that despite the conflicts common between women married to the same man, Eshkar and Gitlam never seemed to quarrel. They amicably drink from the same cup, just not at the same time. I shared a bed with Gitlam exclusively for the wedding week, during which I learned that despite his being tutored in marital skills by Eshkar, his bed practices were different than his brother’s.

Maggie: You don’t need to go into details.

Shifra: “It’s like with my sons. They’re different, but I love them all and don’t prefer one over the other.”

Maggie: Which brother is the headman? When a man has more than one wife, one of them, usually the eldest, is the head wife.

Shifra: Eshkar, older than Gitlam by several years, has been his family’s headman ever since his father and uncle died together when a hippo overturned their fishing boat. But now that he and Gitlam live with my family, Grandfather is still the headman.

PREORDER HERE

—

Maggie Anton is an award-winning author of historical fiction, as well as a Talmud scholar with expertise in Jewish women’s history. She was born Margaret Antonofsky in Los Angeles, California, where she still resides. In 1992 she joined a women’s Talmud class taught by Rachel Adler. There, to her surprise, she fell in love with Talmud, a passion that has continued unabated for thirty years. Intrigued that the great Jewish scholar Rashi had no sons, only daughters, she started researching the family and their community.

Thus the award-winning trilogy, Rashi’s Daughters, was born, to be followed by National Jewish Book Award finalist, Rav Hisda’s Daughter: Apprentice and its sequel, Enchantress. Her latest work is The Choice: A Novel of Love, Faith and the Talmud, a wholly transformative novel that takes characters inspired by Chaim Potok and ages them into young adults in 1950s Brooklyn. Since 2005, Anton has lectured about the research behind her books at hundreds of venues throughout North America, Europe and Israel. She still studies women and Talmud, albeit mostly online. You can also friend her on Facebook and Goodreads.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing