Authors Interviewing Characters: Elaine Neil Orr

Elaine Neil Orr, interviewing Isabel Hammond from Dancing Woman, Blair, 2025

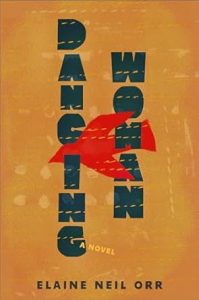

DANCING WOMAN

Elaine Neil Orr, born in Nigeria to expat parents, brings us an indelible portrait of a young female artist, torn between two men and two cultures, struggling to find her passion and her purpose.

Elaine Neil Orr, born in Nigeria to expat parents, brings us an indelible portrait of a young female artist, torn between two men and two cultures, struggling to find her passion and her purpose.

It’s 1963 and Isabel Hammond is an expat who has accompanied her agriculture aid worker husband to Nigeria, where she is hoping to find inspiration for her art and for her life. Then she meets charismatic local singer Bobby Tunde, and they share a night of passion that could upend everything. Seeking solace and distraction, she returns to her painting and her home in a rural town where she plants a lemon tree and unearths an ancient statue buried in her garden. She knows that the dancing female figure is not hers to keep, yet she is reluctant to give it up, and soon, she notices other changes that make her wonder what the dancing woman might portend.

Against the backdrop of political unrest in Nigeria, Isabel’s personal situation also becomes precarious. She finds herself in the center of a tide of suspicion, leaving her torn between the confines of her domestic life and the desire to immerse herself in her art and in the culture that surrounds her. The expat society, the ancient Nigerian culture, her beautiful family, and even the statue hidden in a back room—each trouble and beguile Isabel. Amid all of this, can she finally become who she wants to be?

This interview takes place after the end of the novel in Richmond, Virginia, Byrd Park Court, Historic District

Me: Am I early? I thought we said noon.

Isabel Hannond: Oh, right. Is it already noon? I lose track of time when I’m painting.

Me: I can understand. That’s how I am when I’m writing.

Isabel: Come in. Catherine is with her father somewhere. We’ll have tea. We’ll sit in the kitchen.

(Seated)

Me: Thanks so much for taking the time to visit. I’ve missed you.

Isabel: I know the feeling. Of missing.

Me: It must be hard living in two worlds. I mean, your Catherine was born in Nigeria. And now she’s, what, two and a half and you’re on the other side of the Atlantic. How did she adjust to the U.S.? It must have been disorienting.

Isabel: It was at first. She wouldn’t wear her shoes, even when it snowed in late November. She would peel her clothes off outdoors. Now that she’s finally gotten used to things here in Virginia, I find I’m the one who is homesick. For Nigeria, I mean. No one here understands who I am anymore. They think it was a hardship living there because we didn’t have air conditioning or television and couldn’t run to the A&P at four in the afternoon and pick something up dinner. We had to plan, you know, sometimes weeks in advance, to have what we needed. But life seemed easier.

Me: You had some very important friendships. You had more than a friendship with a particular gentleman.

Isabel: And there’s no one to talk with about it. My dear Dutch friend, Elise; I could tell her the most damning things about myself and she still loved me. She understood. I don’t have anyone like that here.

Me: Yet. You don’t yet.

Isabel: I don’t know if I ever will. Those four years were so full. I was newly married, trying to impress my young husband and the people in his USAID world. I lost myself. And I nearly lost him, my husband, Nick, in more than one way. Ultimately I think I found myself. Those years were like an enormous, muscular wave. I don’t think I could withstand that kind of shifting and change and discovery again. The kettle!

(Pause)

Isabel: Your tea. I hope it’s okay. I added a square of sugar and just a little cream.

Me: It looks delicious. Tell me more about your homesickness.

Isabel: I miss smells. The smell of fires. Or the market. Or the rain. We have rain in Virginia, but it doesn’t pound the earth so hard nor does it raise such a bouquet of earth smell. We lived more outdoors there. It was also easier to get out with my paints. I could just walk out the backdoor and down the lane and find something to paint: a goat, a tree, a woman pounding yam.

Me: Don’t similar scenes occur here, very close by? Wasn’t your first painting of a bird, a robin as I remember?

Isabel: Sure. I guess it’s seeing things for the first time that makes them magical. It’s hard to see something newly when it’s common to one’s first world. But, you know, that’s what art is really about, painting, I mean. Seeing something again for the first time. That’s what my first teacher taught me, the one who helped me with the robin. It must be the same with writing; you’re trying to get readers to see the ordinary world as extraordinary.

Me: Exactly. Dishwashing can be a euphoric experience for a character who is thinking through a problem and suddenly comes to an insight because of the way a bubble grows in size and reflects light and then finally pops.

Isabel: Now you make me want to dirty some dishes so I can paint bubbles. Catherine would love to help me with that particular painting.

Me: Are you finding ways to teach now that you’re back in Virginia? I know how you poured yourself into teaching the young Hausa children in Kufana. I was actually a little surprised by that since at the time you were still a little insecure about your own capacities.

Isabel: I have! I’m rotating among three middle schools here in Richmond. I go to several classes at each school once a week eleven, twelve, thirteen year olds. We try a little of everything. I started with clay because they’ve used Play Doh and it feels familiar to them. We start with slab pots and then we try a mug and, at the one school that has a wheel, I let them try throwing a pot. Even if it’s imperfect, we dry and fire it and then they get to glaze it and see how it comes out of the kiln. We’ve also done macrame and collages and drawing. And next is watercolor. I’m especially excited about that, as you may imagine.

Me: Are they as excited and creative as your students in northern Nigeria?

Isabel: Ultimately, yes. But I have to coax them. They grew up with coloring books. They think there’s a particular way to create an image on the page. Their first efforts are often predictable and lack much personality. I really have to get them to release their imaginations. I ask them to put their pencil on the page and tell them to draw something without ever lifting pencil from paper. This really loosens them up. They’re surprised to see that what they end up with is actually more interesting than what they had tried to copy even though the lines overlap and go sideways and repeat. I even put blindfolds over them and ask them to draw without seeing. We have great laughs over the results. But sometimes what they come up with is uncannily like the object, only in a new way they couldn’t have planned. Once they let go a little, they’re freer to step away from convention and into imagination. That’s where I really see growth.

Me: That must be very rewarding.

Isabel: It is. As long as I’m teaching, I have to keep experimenting and growing.

Me: That sounds like a great anti-aging device.

Isabel: It is! So you must keep writing as well.

Me: I will! No doubt about it.

BUY HERE

Elaine Neil Orr is the author of five books, including the novels A Different Sun and Swimming Between Worlds. She was born and grew up in Nigeria, the daughter of missionary parents, and most of her writing is grounded in both the American South and the Nigerian South. She is a professor of literature at N.C. State University and serves on the faculty of the Brief-Residency MFA in Writing Program at Spalding University. She lives in Raleigh. https://www.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing