Why Are We Afraid To Talk About Death?

Photo by Kristina Amelong

Death is a constant presence, an inherent part of life, a fact of humanity. Yet in much of western culture, we pretend this isn’t the case. We are afraid to talk about death, or acknowledge it in any way. We avert our eyes, lower our voices, and avoid bringing up our own or others’ losses, as if that will protect us from the heartbreak.

But it won’t, as I know all too well.

I was seventeen when my thirteen-year-old brother Jay was killed while riding his bike—an accident he had predicted over a year in advance, down to the color of the car that hit him. He told us he’d seen his fate in a dream. “I will die young,” he told my mom and I repeatedly, his voice calm and sure. “It won’t be much longer, I want you to be prepared.” He stated it as a simple fact, a truth he carried like a quiet flame. Yet for those of us who loved him, those words were heavy, almost unbearable. We didn’t want to hear them. We couldn’t face the possibility of his absence, couldn’t swallow a reality in which accidental death was imminent, let alone foreseeable. We tried to ignore his message.

Then, when Jay’s tragic death unfolded exactly as he told us it would, we tried to deny reality. My mother retreated from the world, and from me. There was no space to grieve and no one to grieve with, as if everyone who had known Jay had died along with him. From the few people who remained in my life, I repeatedly got the message that I needed to move on and get over it, so I turned to drugs and alcohol, common coping tools in my family culture. I tried to forget I’d ever had a little brother, to live within a mirage of marijuana smoke and drunken one-night-stands. It wasn’t really living, but for a while it was the best I could do.

Photo of Jay, Kristina’s mother Carol, and Kristina I, taken by a Victorian photo service circa 1978.

The thing that really scared me straight, so to speak, and helped me get into treatment, was actually my heightened fear of death. I realized that if I continued on the way I was going, my mother wouldn’t have any living children, a tragedy that seemed too great to allow. I got clean and sober, though I lived in constant terror. I had formed a conclusion that death was all around, haunting me, that it is inherently traumatic, painful, inevitable. From what I can see, this is how many people relate to death, especially those who have experienced loss firsthand.

Now, however, after more than thirty years of healing through counseling, meditation, crying and screaming, colon cleansing, and so many other therapies, not only am I living healthily into my sixties; I have an entirely different perspective on death. I believe what Rainer Maria Rilke wrote: “Death is our friend precisely because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, that is natural, that is love.”

Jay seemed to live by this understanding, as if he had made peace with death’s proximity. He lived with urgency and purpose, not as if he were racing against time but as if he were deeply aware of its fleeting nature. His words and actions held a weight, a depth. Though I didn’t realize it until much later, it was a gift to be close to someone who was unafraid to face the inevitable head on. Death presses us to cherish what we have. Jay’s ability to embrace this truth taught me that to speak openly about death is to honor life. In denying it, we lose sight of what makes each moment sacred.

This isn’t to say I’m disconnected from all fear surrounding death—I still feel fear from time to time, and honor that fear in myself and others. Death carries so many unknowns, so many questions: What happens when we die? Will I be remembered? Will it hurt? Is it the end of consciousness? These questions demand a closeness to truth, and truth can feel too raw, too exposing. To speak of death is to confront our own impermanence and the fragility of everything we hold dear. Yet if we only live in the avoidance of death, we miss the opportunity to be intimate with what does bring us to truth.

It took many years before I could speak openly about Jay’s death, and after I started to do so, each time brought more healing. I understand why we avoid the conversation. Death is unpredictable, beyond our control. To admit its inevitability feels like surrender, like giving up the illusion that we can keep what we love forever. But I have learned that in speaking of death, we are not surrendering; we are awakening. We are making space to cherish the fragile beauty of life, to notice its fleeting wonders; to ponder the mystery of consciousness, to notice its cosmic nature.

Photo of Kristina’s brother Jay as a boy, taken by her mother Carol.

A couple years ago, a friend of Jay’s told me a story about Jay that shocked me. Apparently, minutes before the accident that would kill him occurred, Jay announced, “I don’t care what happens to me when I die!” Could it be that knowing the certainty of his death erased the fear of the unknown that most of us feel? What if death isn’t an end, but a transition? Carrying the torch of Jay’s story has taught me that death holds a profound mystery—one that underscores the beauty of life. Instead of fearing it, we can view it as a teacher, inviting us to live more fully. In talking about death, we can learn how to live.

—

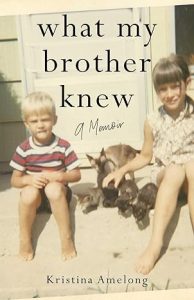

WHAT MY BROTHER KNEW: A MEMOIR

For readers who were inspired by Alua Arthur’s Briefly Perfectly Human, an emotional, eye-opening account of one woman’s journey from loss and abuse to healing and spiritual awakening.

For readers who were inspired by Alua Arthur’s Briefly Perfectly Human, an emotional, eye-opening account of one woman’s journey from loss and abuse to healing and spiritual awakening.

As a boy, Jay Amelong predicted the accident that caused his death, down to the color of the car that hit him. “I will die young, while riding my bike,” he told friends and family repeatedly. “It won’t be much longer, I want you to be prepared.” These were baffling words to hear from the mouth of a content thirteen-year-old—but when Kristina Amelong was only seventeen, her brother’s tragic death unfolded exactly as he said it would, radically changing her life.

Propelled down a self-destructive path of drug addiction and reckless sex, Kristina spent much of her young adult years wanting to die. Once or twice she came close. Always, Jay’s bizarre story and his inexplicable acceptance of his own death lived in her body.

More than thirty years after losing Jay, Kristina embarks on a journey of discovery, seeking truth about herself, her brother, and the universe. The result of her investigation is a memoir that defies belief. Charting a life path from loss and abuse to healing and spiritual awakening, What My Brother Knew demonstrates the transformative power of facing the mystery of death head-on and our incredible ability, as humans, to do just that.

BUY HERE

Kristina Amelong is the founder and owner of Optimal Health Network, a holistic health business. She has written two books: Ten Days to Optimal Health: A Guide to Nutritional Therapy and Colon Cleansing and What My Brother Knew: A Memoir. She is a senior board member for the Center for World Philosophy and Religion, a nonprofit organization dedicated to a reweaving of the human story that will guide humanity through the current evolutionary crisis. She has a passion for photography, gardening, and pickleball. Kristina resides in Madison, Wisconsin, with her three dogs and a brood of chickens.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing