A FEW THOUGHTS ABOUT ART AND WRITING

When I was seventeen my father gave me an autobiography called The Magic of a Line. It’s out of print now and the author Laura Knight, an English Impressionist artist, is relatively unknown in America. The book has sat on my bookshelf for years. I’ve always kept it despite many moves, partly because it was my father’s gift to me—he inscribed it—but also because I loved the title. The line referred to is that of drawing, but it could just as well relate to the line of a story. The magic of a line is just one of many principles shared by the crafts of painting and fiction.

Beginning artists learn how to outline a subject and to grasp the essential shape of an object, whether that’s a tall vase of flowers, a flat horizon in a landscape, or the curve of a figure’s back. A skilled artist can use a line to provoke an emotional response even without using color to fill out the form. The artist Degas had great respect for line drawing and is quoted as saying, “Drawing is not what you see but what you must make others see.” His colorful paintings of ballerinas and horses are strengthened by the bold outlines and compositions of his preliminary sketches.

People often ask me how I approach my own watercolor botanical paintings. The answer: I start with a pencil drawing. By following the form of a flower, stem, and leaves, I can position a painting on a page without thinking too much about the composition. Nature excels at composition! I’m always impressed at how little I can convey of a flower’s complexity and true color. However, a good drawing is a beginning.

I’ve practiced painting all my life, but have only come to appreciate the aesthetic and artistic possibilities of writing relatively recently. As I took classes in fiction writing and learned more about the craft, I found that many principles I had learned in painting applied also to writing. Line is just one of them: the storyline in a novel serves a similar function to the drawing in a painting. Sometimes called a through-line, it’s the thread, usually about the protagonist, that runs through the entire work, one that holds the fabric together and allows the story to fray around the edges. Without the framework, a long story would be difficult to follow, in the same way that a painting might appear confusing if the composition lacked the skeleton of a drawing.

In researching material for my novel Estelle, I found information about Degas’s technique for creating strikingly bright whites. Many of his paintings of dancers exemplify his skill at painting dancers’ dresses which appear almost luminescent on stage in the glare of the spotlight. He used a black monotype shape under an application of white paint tinted with undertones of blue, yellow, or pink, then reinforced the image with pastel strokes to create the impression of the gauzy material. Degas’s compositions have a strong graphic sense, in large part because of the dark outlines.

In the same way that a painting needs a framework, a good story needs a plot, a series of events that holds the reader’s attention from beginning to end. Writers have different approaches to developing it. Some outline scenes at the beginning, while others write and make things up as they go along. In the end, it doesn’t matter which approach they use, as long as the story makes sense and is satisfying to the reader.

A good painting needs differences in value, areas of dark as well as light. Degas’s dancers shine against subdued backgrounds, producing scenes bursting with drama. Writers create tension and drama by moving a story from a place of calm to a place of discomfort. While words, dialog, and actions can relay drama, the reader can experience it best when the writer portrays the contrast between calm and unsettled states in hyper-reality.

Mood, or ambiance, draws the viewer or reader into the story of a painting or novel. A painting can sometimes appeal solely on the merits of its mood, where color can set the tone. A landscape consisting of mostly gray and brown tones appears somber; the same scene in blue and yellow looks cheerful. The predominant tone of a novel might be described as dystopic, comic, or tragic. Without a distinctive and appropriate atmosphere, any work may seem flat.

Of utmost importance in art of any genre is the artist’s voice, the characteristic that makes every painting and every book unique. Degas’s brush strokes, his slanted compositions, his layered rendering of dancers’ dresses, his bold colors, are almost instantly recognizable. A writer’s style is like a handshake.

The more I understand about these artistic principles, the more my admiration grows for artists and writers who have mastered their craft. But no matter how skilled, most of them appreciate encouragement to produce their best work. Estelle, Degas’s cousin, encouraged him to paint family portraits while visiting her and their Creole relatives in New Orleans in 1872. It was a time when the artist questioned his artistry and the direction to take in his work. He reluctantly completed paintings of several individual family members until, shortly before he left New Orleans, he painted his family’s cotton business, a large painting depicting his brothers and uncle at work. The result, A Cotton Office in New Orleans, established his reputation.

—

Linda Stewart Henley is an English-born American who moved to the United States at sixteen. She is a graduate of Newcomb College of Tulane University in New Orleans. She currently lives with her husband in Anacortes, Washington. ESTELLE is her first novel.

Find out more about her on her website https://www.lindastewarthenleyauthor.com/

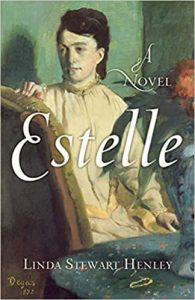

ESTELLE

When Edgar Degas visits his French Creole relatives in New Orleans from 1872 to ’73, Estelle, his cousin and sister-in-law, encourages the artist―who has not yet achieved recognition and struggles to find inspiration―to paint portraits of their family members.

When Edgar Degas visits his French Creole relatives in New Orleans from 1872 to ’73, Estelle, his cousin and sister-in-law, encourages the artist―who has not yet achieved recognition and struggles to find inspiration―to paint portraits of their family members.

In 1970, Anne Gautier, a young artist, finds connections between her ancestors and Degas while renovating the New Orleans house she has inherited. When Anne finds two identical portraits of Estelle, she discovers disturbing truths that change her life as she searches for meaningful artistic expression―just as Degas did one hundred years earlier.

A gripping historical novel told by two women living a century apart, Estelle combines mystery, family saga, art, and romance in its exploration of the man Degas was before he became the artist famous around the world today.

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing