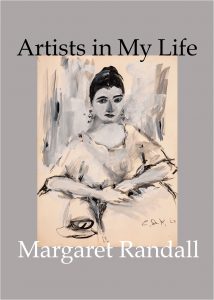

Artists in My Life: Process and Product

Margaret Randall

Of the many books I have written in my 85 years, Artists in My Life may seem like a departure. It’s not. I have always had a profound relationship with visual artists. My mother was a sculptor and the original work of many artists hung on the walls of my childhood home. Visiting museums was a thrill in any city where we traveled. During the late 1950s and early 1960s I lived among the abstract expressionists in New York City; they became close friends, some of them mentors. In Mexico, where I founded and for eight years edited an important bilingual literary quarterly, EL CORNO EMPLUMADO / THE PLUMED HORN, we published drawings by hundreds of vanguard artists. I continued to have many artist friends, as I went on to live in Cuba and Nicaragua.

Of the many books I have written in my 85 years, Artists in My Life may seem like a departure. It’s not. I have always had a profound relationship with visual artists. My mother was a sculptor and the original work of many artists hung on the walls of my childhood home. Visiting museums was a thrill in any city where we traveled. During the late 1950s and early 1960s I lived among the abstract expressionists in New York City; they became close friends, some of them mentors. In Mexico, where I founded and for eight years edited an important bilingual literary quarterly, EL CORNO EMPLUMADO / THE PLUMED HORN, we published drawings by hundreds of vanguard artists. I continued to have many artist friends, as I went on to live in Cuba and Nicaragua.

In 2015, I was invited to lead a gallery tour for Elaine de Kooning’s exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. Preparing the script I would use, I realized I’d written more about visual art than I thought. Eventually I expanded that text, and it became the first chapter of this book. A fortuitous reconnection with the daughter of two sculptors who visited us in Mexico in the mid-sixties led to the research and memories that went into chapter two. I began to think seriously about the visual artists whose work has accompanied and impacted my creative journey. Names like Leandro Katz, Jane Norling, and Gay Block came to mind. I knew I wanted to include photographers, sculptors, muralists, and architects, as well as painters. Soon I realized that I had a great deal to say about the artists I have known, and the book unfolded from there.

Artists in My Life speaks in revealing ways about a dozen or so visual artists whose work has impacted my own. Some drew on rock walls or in desert sands thousands of years ago. Some were mentors or close friends. Some I never met but their work is a constant. One I married. I look at these artists’ lives and at what they have created from interwoven angles: as makers of art, social commentators, women in a world dominated by male values, and in solitude or collaboration with communities and the larger artistic arena. I go beneath the surface, asking questions and telling stories.

I have wanted to answer questions such as: Why is it that visual art—drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, architecture—grabs me and, in particular instances, feels as if it changes me at the molecular level? Where does the image continue to live in my memory and how do art and memory interact? How do reason and intuition come together in art? In what ways is art necessary to the health of society? What does it take to be an artist? What is it about the work of certain artists that touches my emotions? Do women and men make art differently? What have women artists had to give up in order to make their art? What does anyone who devotes his or her life to making art have to give up in societies that don’t support artistic creativity? How do sexual identity—male, female, lesbian, gay, transgender, and nonbinary—as well as class, race, and ethnicity impact the making of art? Does great art change the viewer? Does it change the artist? How does art act upon human relationships? Upon the environment? Upon the future? Can art calm violence, heal the human spirit? How has art making preserved ancient ways of telling or recast itself across cultures and centuries? What impact do new—or old—technologies have on the art-making process? How does art travel through time? Are visual artists different from the rest of us; how are they shaped by the ways in which they understand and render perception, perspective, energy, scale, color, line?

To respond to these questions, I’ve dug deep, interrogating my living subjects as well as those artists long gone by looking at their lives and work through the lenses of class, race, gender, and culture. Those who are friends were forthcoming through many conversations and generous in allowing me to reproduce their work. I’ve reached back to examine art left ten thousand years ago on rock walls in the canyons of the US American Southwest and compared it with what members of the mural movement paint on modern-day walls in San Francisco. I’ve considered the intricate drawings made by European explorers of Mexico’s Maya kingdom and a photographer who looked through his camera at the same structures several hundred years later. Time and place are also protagonists in this book.

And of course, I wanted a publisher who would be willing to design the book like the work of art it should be, including the more than 60 full-color plates that illustrate the text. Previous experience with New Village assured me it was the press I wanted for this project, and I was happy when it found a home there. From the very beginning of its time in the world, Artists in My Life has generated the kind of response I’ve hoped for. Mary Gabriel, who provided one of the book’s two forewords, wrote: “In reading Artists in My Life, we, the readers, become part of Margret’s expanding universe, and she part of our.” Ed McCaughan, in the other, explains: “A photographer’s eye, a poet’s voice, a woman’s sensibilities, a revolutionary feminist’s consciousness, an oral historian’s understanding of biography bounded by time and place: Margaret Randall brings all these to this meditation on some of the artists and artworks most meaningful to her life.” Art historian Roberto Tejada says: “These essays on the radiant living that art enables are crafted with an eye to scene structure and narrative economy within the accidental landscapes of recollection. Randall’s accounts relate forms as configured differently by artists, many of them women, who have challenged the social calibrations of power and its interpersonal complexities.” And readers who may not have given much thought to the connections between visual and written artistic expression, have begun to contact to me with their own stories to tell.

—

Margaret Randall is a feminist poet, essayist, translator, photographer, and social activist. A New York native, she lived among the city’s abstract expressionists in the 1950s, Mexico in the ‘60s, Cuba in the ‘70s, and Nicaragua in the ‘80s. She returned to the US in 1984 only to fight deportation due to the controversial content of her books. She is the founder and former editor of the bilingual literary journal El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn, which started an iconic bridge between cultures in the 1960s. She has more than 150 published books in several genres.

https://nyupress.org/9781613321591/artists-in-my-life/

Category: On Writing