Author Interview: Jennifer Ouellette

Jennifer Ouellette is a science writer and blogger in Los Angeles, California. She is the author of three popular science books for the general public, and has been published in a number of different magazines.

When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer, and what influenced your decision to choose this career? Why did you decide to go into science writing?

If you ask my mother, she always knew I would be a writer of some kind. It’s probably more surprising that I can actually make a living as a writer. I could read by a very young age and quickly became a voracious bookworm and lover of words. It was just a matter of time before I started creating my own oevre, I suppose.

When I was in grade school, I wrote a bunch of short stories and several very bad poems – more like ditties, actually, since I had only a faint grasp of what poetry was supposed to be. And by junior high, I’d penned a complete romance novel – also very bad, and more risqué than my naïve 12-year-old self realized. I majored in English in college, and edited my college newspaper, but when I moved to New York City after graduating, I was just one of thousands of aspiring writers in the Big Apple.

I didn’t plan on becoming a science writer; it was just a coincidence. I needed a job to pay the rent and took a position with the American Physical Society, the leading membership organization for physicists in the United States. They needed someone to write up short news stories for the membership newspaper and that led to covering the actual research presented at meetings, and writing for other science publications. I had no idea this was an option, and it turned out to be the perfect career for me.

What do you find to be the biggest challenge in science writing?

Because I lack a formal science background, one of the biggest challenges (especially starting out) was to make sense of the science – physics is a pretty esoteric subject with some very specialized jargon. Although the concepts and experimental descriptions were straightforward enough, once I translated it all into plain English. In the long run, though, all that extra research gave me a pretty decent informal science education.

Another writer, many years ago, took offense when I mentioned that I found science writing more difficult than the other things I’d written. It’s true that all writing is hard; every form has its challenges. But science writing is still unusual, I think, because it’s so incredibly difficult at times to preserve accuracy while still making it accessible – and being honest about where there is bona fide “debate” versus strong consensus. There is always the temptation towards false equivalence in the culture of journalism, but often, in science, there is a right and wrong answer, albeit a nuanced one. You can’t present both sides fairly if one side is flat-out wrong (e.g. climate change, the anti-vaccination movement, “free energy” schemes). Those are just a couple of the unique challenges inherent in science writing.

How would you describe your books to someone who has never read them?

I write popular science books for people like my former self, who hated math and physics in high school and have avoided the topics ever since. We miss out on many wonderful things by doing so, as I discovered when I started interviewing physicists and visiting labs. It’s nothing like what we were taught in high school (the standard high school curriculum basically stops at Isaac Newton in the 17th century). It’s about curiosity and discovery, and I am continually in awe of what scientists accomplish.

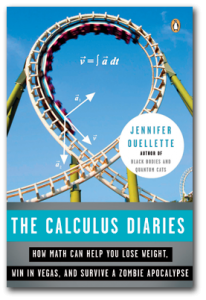

So that’s what I try to convey, by making it relevant to daily life, with references to popular culture wherever I can manage to include them. For example, in The Calculus Diaries, I showed how the rides at Disneyland, gas mileage, architectural arches, zombie epidemics, and house-hunting could all tie into mathematical functions in calculus.

What has been the highlight of your writing career up to this point?

Each one of my books has been a highlight, but honestly I was most thrilled about the use of the opening paragraph of The Calculus Diaries in the New York Times acrostic puzzle one Sunday. I’m a crossword fan, needless to say, and did those New York Times Sunday puzzles religiously for years, so to see my own book being featured – well, that was a special moment.

Tell me a little bit about your Scientific American blog, Cocktail Party Physics, and your alter-ego, Jen-Luc Piquant. What prompted you to start blogging, and what do you hope readers will take away from reading your blog?

Cocktail Party Physics only recently moved to Scientific American a year ago, after five years as an independent blog. I started it when my first book came out, on the advice of my then-editor, and found I was a natural-born blogger. It’s very much in the spirit of what I do, namely, provide a lively account of physics and related research, tied in with popular culture and/or daily life – just enough to give you something to chat about at the average cocktail party. The original blog even had a bunch of physics-themed cocktails in the sidebar, although those didn’t fit in with the Scientific American site design. Jen-Luc Piquant started out as the little mood avatar at the start of each post. I thought it would be fun to name her, and she kind of took on a life/persona of her own. You can read the full backstory here.

—

Visit Jennifer’s website.

Connect with Jennifer on Google+ or subscribe to her Facebook page.

Follow Jennifer on Twitter: @JenLucPiquant.

Browse Jennifer’s novels on her Amazon author page.

Category: Being a Writer, Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing, US American Women Writers, Women Writers, Women Writing Fiction

I find this fascinating because, like you, I was turned off science in school but it now intrigues me and it is difficult to study without the foundations. I am utterly intrigued by light but have wondered if I really could study it. If I could find an accessible book on the subject I would buy it. Thank you for this.