Channelling Marilynne: Translation as Possession, Envy and Belonging

By Gwen Davies, translator of The Jeweller by Caryl Lewis

‘I get it!’ my author announced. ‘You may not be on my side but you definitely want the best for my work.’ She’d just been at the brutal end of my red pen as we came towards the end of several proofs with me as creative-, then copy-editor then creative proofreader of her crime novel set in Rhyl.

Gwen Davies (pic by Jessica Raby)

Oh, I see,’ said another, light dawning as we both emerged from Round Three as her London-set male first-person narrative about music, homelessness and suicide lay palpitating but still alive on the ring floor. ‘You care so much about my novel because it reflects your taste in books!’

A third, whom I was mentoring (comfy-sounding but with same knife-wielding potential), was flushed, in a happy way, as we came out of our final meeting. ‘What I love most,’ this author of a satirical campus novel about metrocentricism chirruped, ‘is that you talk about my characters as if they’re real.’ She’s right: I do, and they are real to me, if she’s done her job. And my job is to give her work a workout, not to give her Reiki Healing.

What have these salutary tales to do with translating from Welsh a gothic novel about rebirth, possession, belonging and envy called The Jeweller?

Well, my theory is that editing is an elevated form of reading; translation is an enhanced level of editing, and that reading leads to a superlative level of imagining, a facility for which belongs to us all. I may have started off sounding arrogant but you’ll come to see that my approach is profoundly democratic.

The setting of a fine harbour town goes through the mill of Reader Jacob’s mind and may hook into a memory of some Regency house he once visited. Or a character like Mari (lodging alongside a monkey, an emerald and some vintage nighties) catches the tail-echo of someone Reader Esther once met and spins into visions of who she would like to become. Or Reader Martha starts dreaming the dialogue of a middle-aged market-stallholder called Mo, with a line in tiger-print bras, and wakes up speaking with a slight west Wales accent. What was once an author’s possession now belongs to the reader; to us all. An image, resonance, dark motivations and the denouement, all become transformed in the grit of each of our individual imaginations. Writing is about the pulls and levers but in reading lies the magic. I’m on side of the reader.

Are you saying that a translator comes to possess a novel she is working on, in the same way that an author ‘owns’ their book?

Well, that is contested territory, the subject of much academic theory and debate around translation and authorship, which, one could argue, might be coloured a little green by envy for the translator’s ‘easier’ craft (the translator gets to write a book without worrying about plot, characters or setting: all they have to do is ‘do’ the language and approximate a voice). Or paranoia (the author can remain blissfully ignorant of a translator’s battles to get her name on a cover or copyright notice). But I repeat: translation is an enhanced level of editing. And, for me, it means that the language will receive an even greater degree of pummelling.

Caryl Lewis, photo by Keith Morris

Are you suggesting that an author’s creation is just grist to your mill as translator, or even that such work is in need of ‘improvement’?

No, I’m not. But the process is a creative collaboration, of the original author’s imaginative world, culture and language, and the translator’s ditto, having been filtered through, in this case, my own subjective imaginative seawater. And whatever careful patterning I may have achieved, of alliteration, so that it falls roughly in the same paragraph as this author had in her original…. Or whichever attempts of mine were successful to convey in English Caryl Lewis’ use of the ancient strict-metre Welsh poetry in prose…. The translation still has to work on its own terms, in English, without recourse to footnote or borrowed quotation.

You’ve talked about ‘belonging’, ’envy’ and ‘possession’ in relation to the translation process: how are these themes relevant to the novel?

The protagonist, Mari, was left a foundling on church steps, and brought up by the vicar. She lives alone, apart from a cat and pet monkey. And while running her thrift and jewellery stall in a market threatened by redevelopment, she might seem to be at the hub of a community and its history – as she does helping Mo with local house clearances – she remains apart. She’s troubled by her lack of family and it’s her mission to find it by combing through letters and cast-off possessions.

Her craft in setting the perfect emerald, and the kitting-out of a beautiful doll’s house, explore an individual’s quest for finding a better fit. Possession and envy are very close cousins. Mari becomes almost possessed by the emerald – which represents her worst insecurities – as she cuts it. And envy is part of that dark force. She holds both a lover and his son far too tightly, and fails to see their own wider settings: a wife, a real mother; other people whose power and right to love may be truer than her own. Without giving the plot away, Mari must seek and find before she can herself give away her old, troubled identity.

Which brings us to the final theme you mentioned?

Yes: rebirth. In a Welsh-language novel, the undercurrents, language and symbolism of faith remain, and it can be a challenge to reinterpret that to a more secular, or indeed multicultural UK-wide readership. But I tried to think of Caryl’s themes of baptism – and all its innovative manifestations in stand-up washes, fever-bathing bandages and sea-soaked swaddling – in American Mid-western terms. I tried to channel Marilynne Robinson in Gilead. I’m sure I didn’t succeed. But envy can be the mother of creation.

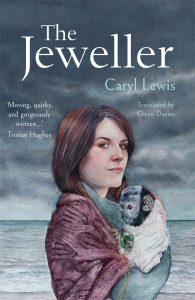

The Jeweller by Caryl Lewis and translated by Gwen Davies, is published by Honno on 19 September 2019 at £8.99

THE JEWELLER

That was the horror of love: your sweetheart could stick a knife into your eyeball and sharpen it a notch every chance they got.Mari supplements her modest stock as a market-stallholder with the trinkets she acquires clearing the houses of the dead. Living in a tiny cottage by the shore – alone apart from a pet cat and the monkey, Nanw – she surrounds herself with the lives of others, combing through letters she has gleaned and putting up photographs of strangers on her small mantelpiece for company.

That was the horror of love: your sweetheart could stick a knife into your eyeball and sharpen it a notch every chance they got.Mari supplements her modest stock as a market-stallholder with the trinkets she acquires clearing the houses of the dead. Living in a tiny cottage by the shore – alone apart from a pet cat and the monkey, Nanw – she surrounds herself with the lives of others, combing through letters she has gleaned and putting up photographs of strangers on her small mantelpiece for company.

Mari is looking for something beyond saleable goods and borrowed memories. As she works on cutting a perfect emerald, she inches closer to a discovery that will transform her life and throw her relationships with old friends into relief. To move forward she must shed her life of things past and start again. How she does so is both surprising and shocking…

—

Caryl Lewis has published eleven Welsh-language books for adults, three novels for young adults and thirteen children’s books. Her novel Martha, Jac a Sianco (Y Lolfa, 2004) won Wales Book of the Year in 2005. Caryl wrote the script for a film based on Martha, Jac a Sianco, which won the Atlantis Prize at the 2009 Moondance Festival. Her television credits include adapting Welsh-language scripts for the acclaimed crime series Y Gwyll/Hinterland.

Translator Biography:

Gwen Davies grew up in a Welsh-speaking family in West Yorkshire. She has translated into English the Welsh-language novels of Caryl Lewis, published as Martha, Jack and Shanco (Parthian, 2007) and The Jeweller and is co-translator, with the author, of Robin Llywelyn’s novel, published as White Star by Parthian in 2003. She is the editor of Sing, Sorrow, Sorrow: Dark and Chilling Tales (Seren, 2010). Gwen has edited the literary journal, New Welsh Review, since 2011. She lives in Aberystwyth with her family.

Category: Interviews, On Writing