Children Need To Write

All the teachers and parents I know are struggling to climb the piles of shoulds and coulds and woulds on behalf of the school age children they care for. They’re making learning choices for students who have been home from school for months, who will now be home all summer, and who may yet still be home next fall.

All the teachers and parents I know are struggling to climb the piles of shoulds and coulds and woulds on behalf of the school age children they care for. They’re making learning choices for students who have been home from school for months, who will now be home all summer, and who may yet still be home next fall.

Nobody thinks parents should try to replicate the traditional classroom. That isn’t possible, or even advisable. In fact, a lot of meaningful learning can take place within our normal family lives, revolving around food, garden, pet and other household tasks. So, I’m not arguing that conventional, sit-at-your-desk schooling is something you should imitate at your kitchen table.

But, even in a typical, non-Covid, summer, children experience literacy learning loss, losing one or two months-worth between school-end in June and back-to-school in late August or September, requiring quite a bit of make-up work when they’re back in the classroom.

According to research gathered by the Brookings Institute, these losses are largely income-based, with middle class students sometimes showing improvement in reading skills in their time out of school, if they experience summer as an opportunity to linger over slow activities like reading, while lower-income students much more often lose those reading opportunities and skills.

Experts call this the faucet theory. They say the educational resource faucet is on for all students during the school year, so everybody learns. But over the summer, for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, that educational faucet slows to a trickle. High-income students continue to get educational opportunities over summer because their parents are in a position to arrange it. It’s easy to imagine–children from wealthy families sometimes have more books at home than children from impoverished families. (And sometimes wealth buys products other than books.)

But why does this especially matter? Education Week says that, “A student who can’t read on grade level by third grade is four times less likely to graduate by age nineteen than a child who does read proficiently by that time. Add poverty to the mix, and a student is thirteen times less likely to graduate on time than his or her proficient, wealthier peers.”

It’s a pretty literal correlation. But the good news is we can interrupt this sad trajectory through creative writing activity. This might matter even more now, in the time of Covid, than it has mattered before, as, for many children, the faucet is off. We can turn it on again.

Creative writing can be a fun activity that interrupts learning loss and supports literacy growth (as well as a lot more than that). When we engage children in positive, non-judgmental creative writing activities, we create the circumstances in which they can learn to love writing and reading and language. That means they’ll not only improve their academic achievement, but they’ll begin to enjoy their education more, starting a virtuous cycle of joy and accomplishment.

To be clear, there are specific ways to ideally lead children to love creative writing, involving non-judgmental response—hearing what they write, showing that it has an effect on you, even if it’s not perfect. There is a lot of time for fixing and the best time isn’t at the very beginning of the process.

But how and why can such non-judgmental creative writing processes achieve this, as compared to, say, grammar flash cards or sentence diagramming? Researchers Broekkamp, Janssen and Van Den Bergh conducted research in Dutch schools that tended to focus their literacy education on children’s ability to read, interpret and appreciate literary texts by known authors. Upper grade students almost never spent time writing creative or literary texts themselves.

They found that creative writing positively influences those academically-desired reading skills. The school-age creative writers they studied developed an eye for style and an awareness of narrative structure that also wound up helping them read and respond to literary texts in academic tasks.

More importantly, creative writing grew students’ general reading engagement and motivation in the literature classroom. Writing creatively made the tested students more interested in reading a variety of books, which tended to set them out on a positive path through adulthood.

According to research by creative writing non-profit, 916 Ink, that isn’t even the biggest benefit of creative writing programs for children. When they write creatively in a supportive environment, they process their anxiety, cope with stress, and build resilience. All of this matters all the time. But especially now.

How does creative writing develop resilience? When children are regularly supported in practicing creative writing tasks, they experiment with inventive processes, which can turn into habits, which then become ways of thinking. They become creative or reinforce their existing creativity. Most studies on the subject suggest that resilient people are creative people, whether because it is a natural personality trait, a learned behavior or a practiced habit.

Children in the habit of working creatively can see a thing in a variety of ways. They can connect dots the rest of us can’t. They can reframe difficult scenarios, which is a defining trait of resilient people. Creative children can find new ways to respond to their problems and stresses.

Also, creative writing stimulates our alpha waves, causing a state of relaxation, in which we’re more likely to have an aha moment and find a solution to what troubles us.

Maybe the most-relevant side effect is that when children are supported in a creative writing practice, they then begin to understand that their own voice is important, that they have a right to use it, that they have reason to use it. They can see through the writing and sharing of their own creative ideas in a positive setting that their words have power. And there is very little the world needs now more than for children to believe in their own power to make positive change, to move mountains and molecules with their words.

—

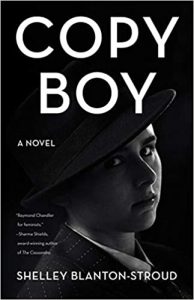

COPY BOY, Shelley Blanton-Stroud

“This is Raymond Chandler for feminists.” ―Sharma Shields, author of The Cassandra

“This is Raymond Chandler for feminists.” ―Sharma Shields, author of The Cassandra

Jane’s a very brave boy. And a very difficult girl. She’ll become a remarkable woman, an icon of her century, but that’s a long way off.

Not my fault, she thinks, dropping a bloody crowbar in the irrigation ditch after Daddy. She steals Momma’s Ford and escapes to Depression-era San Francisco, where she fakes her way into work as a newspaper copy boy.

Everything’s looking up. She’s climbing the ladder at the paper, winning validation, skill, and connections with the artists and thinkers of her day. But then Daddy reappears on the paper’s front page, his arm around a girl who’s just been beaten into a coma one block from Jane’s newspaper―hit in the head with a crowbar.

Jane’s got to find Daddy before he finds her, and before everyone else finds her out. She’s got to protect her invented identity. This is what she thinks she wants. It’s definitely what her dead brother wants.

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: How To and Tips

Today generation are very active and hard to control parents and teacher have to focus more to children