Consequences of Truth-Telling: Self-Censorship in Memoir

Consequences of Truth-Telling: Self-Censorship in Memoir

Consequences of Truth-Telling: Self-Censorship in Memoir

Memoirists tell the truth. Whether it’s about abuse, the trials of parenting, sex, or marital conundrums, we tell the truth without inhibitions. At least, that’s the rule. That’s the goal. The fact that people will read your truth is a whole other concern that is most disconcerting to memoir writers.

How can you give voice to your reservations about mothering with the knowledge that your children will one day read those internal thoughts that you bury with easy smiles and expected sacrifice? How can you write about your marriage and the secret passions you encounter in the smile and touch of other men, possibly other women, when your spouse is sure to read all about it? How can you write about your children’s sexuality as bi, gay, or trans when you know that you will be outing them and that coming out is a step only they can take for themselves?

How can you express your dissatisfaction with life, with your family, with your role as wife and mother, while still entrenched in date nights and carpools and SAT and college-seeking preparations that involve the entire family’s cooperation?

Memoirists write the truth, but quite often the truth is not just about them. Their truth reveals the lives and secrets and pains of those with whom they share their most intimate and personal experiences, and by exposing these truths as their own, they are in fact also exposing those they love — who may not have a choice in this most necessary truth-telling.

How do we choose what to reveal, and if we do, is this real truth-telling or is it self-censorship?

Self-censorship, or soft censorship, is defined as controlling one’s views, words, or thoughts in order to avoid rejection or offending those we care about.

We self-censor all the time, even while not writing memoirs. We are conditioned early on in life to control our tongues so as not to hurt the feeling of those around us, those we love as well as those tied to our aspirations and careers. We don’t often tell the truth because the consequences that come with pure truth can be often quite painful and full of repudiation.

So we lie.

As memoirists, however, our veracity is always in question, so we are held to a higher standard to tell the truth and nothing but the truth, no matter how ugly, morose, or degrading it may be. In some cultures, writing about the family is cause for castigation. An example of this comes to us from an article that looks at the prevalence of memoirs written by Jewish Iranian women like Azra Nafisi, author of Reading Lolita in Tehran, and a few others who have written autobiographies to counter the western stereotypes that limit Muslim women as caricatures of passive and unlearned objects of control.

Farideh Goldin, author of Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman concedes to the pressures she encountered by her own family: “Even before I decided to write my autobiography, I received messages from relatives threatening lawsuits if I spoke about family matters in my [work].”

The wonderful writer and feminist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie notes a similar conflict she encounters when she writes memoir over fiction:

[B]y its very form, memoir is as much about what the writer puts in the book as it is about what the writer leaves out. In writing memoir, I am very aware of my own self- censorship, very aware of the “I” as a character, very aware of protecting people I love… When I write fiction, I am free. I am free of thinking of an audience, free of self- censorship.

In writing memoir, most writers self-censor when they feel they have to acquire permission from the people they write about in their work. This gives others the power to reject the writing that needs to be expressed as well as the writer that needs to exhume the ghosts of her life in order to make sense of it and move on. I don’t believe in asking permission to write, even if in our writing, we expose the behavior of those with whom we share our lives.

It’s another way to silence us, to make us occupy even smaller spaces — not just in our lives but also in the book industry. Our stories have to be told; we need to tell them, or else, we wouldn’t be writers, call ourselves memoirists. We write because we are called to it, and the stories that come from us need to take up as much space as they need to reach our readers.

According to editor and columnist Gabino Iglesias, “Writing requires vulnerability. You have to turn off your self-preservation instincts. You have to take off your skin and dance, bleeding and screaming with your worst nightmares, while your angels and demons watch.”

All writers have to do this, bleed into their writing, but fiction writers are free to conceal their truth behind characters and events that could be centered on real occurrences. Writing your truth as fiction makes the process of writing truth less threatening. Memoirists are sworn to tell the truth, not secrecy.

There is no hiding.

Everything has to be real, honest, even dialogue. We cannot hide, and we shouldn’t want to hide. Our stories give readers words with which to communicate their own pain, a mirror that lets them know they do not exist in oblivion. Stories came to my life when I needed them most, and even today, in my loneliest and most dejected moments, I look for books to guide me in the way that the people in my life cannot and will not. I look to the lives of other women to show me that I am not alone, not forsaken.

I feel seen and accepted in the stories that unfold from real lives lived by women whose experiences reflect my own. And this is why I write, perhaps to give back, to help women’s pain be articulated and seen.

I’m a nonfiction writer. A memoirist. I write out my life whether about my childhood, my sexuality, my marriage, the dark parts of the mothering of my children, and my recurring battle with suicidal ideations. Because I was silenced for the first twenty years of my life, I refuse to be silent in my late forties.

I have found my voice as a writer, and I have to tell my stories not because I am selfish or vengeful but because I will die from the silence if I don’t. In writing memoir, we have to write for ourselves, not for the ones we write about.

Don’t ask their permission.

Only concern yourself with your permission, and tell the truth, no matter how ugly or depraved it is. By censoring ourselves, we censor the parts of our narratives that need to be given voice and form and utterance. Self-censorship is silence and silence deprives us of power. Dance, bleed, and write what you know. All of it.

Spare nothing.

Spare no-one. Not even yourself. As Toni Morrison once noted, “artists must never be silent…there is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That’s how civilizations heal.”

—

Marina DelVecchio is a former high school English teacher with twenty years’ teaching experience in literature, creative and academic writing, and research. She has acquired an MS in English and Secondary Education from Queens College in New York, thirty credits towards her Doctorate at St. John’s University in New York, specializing in Gender Studies, 19th and 20th Century American Literature, and Feminist Criticism, and an MFA in Creative Writing from the Queens University in Charlotte. She has also completed a Certificate in Women’s Studies from the University of Massachusetts – Dartmouth and teaches writing, women’s studies, and literature as a full-time Professor at a local community college in North Carolina.

She has received several awards for her writing from The Writer’s Digest Annual Writing Competition (2011-2015), and her work has been published by The Huffington Post, WE Magazine for Women, The New Agenda, and BlogHer. She has worked as a contributing book reviewer of women’s literature for Her Circle Ezine and as Assistant Editor of Poetry and Non-Fiction for QU Literary Magazine (2014-15). In print, her work has been published by Cengage Learning’s anthology on Media and Violence against Women (2013) and She Writes’ collection of essays titled Three Minus One (2014). She was a finalist in the 2015 Tiferet Writing Contest, and her craft essay on writing immersion memoirs was published by The Tishman Review in June 2016.

Currently represented by the Keller Media Literary Agency for a nonfiction project related to music and female sexuality, Marina DelVecchio has established a strong online presence via her writing on empowering girls and women through education, positive female role models, and writing as an act of resistance.

Find out more about Marina on her website https://marinadelvecchio.com/

Follow her on Twitter https://twitter.com/Marinagraphy

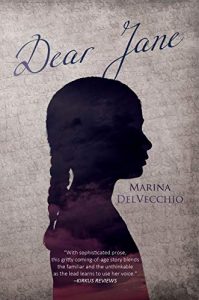

DEAR JANE

Kirkus Reviews’ Best Indie Books of 2019

Kirkus Reviews’ Best Indie Books of 2019

2019 Maxy Awards “Best Young Adult”

“With sophisticated prose, this gritty coming-of-age story blends the familiar and the unthinkable as the lead learns to use her voice.” –KIRKUS REVIEWS

Kit Kat was born in Athens, Greece. Her mother was a prostitute, and their protector was a pimp. After an early childhood marked by violence, homelessness, and time in an orphanage, a Greek-American woman adopted her and moved her to New York. Kit Kat was eight years old, with a new name, a new country, and a new mother who tried to silence her memories and experiences. She sought refuge in books, and after a failed suicide attempt at the age of thirteen, she discovered Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. This book saved her life, and at fifteen, Kit Kat begins to write letters to Jane Eyre as a means of surviving a childhood she still remembers, the family she left behind, and the new mother that refuses to acknowledge her past.

Kit Kat’s letters to Jane Eyre demonstrate the resilience and power that she derives from Jane’s own dark narrative and the parallels between their lives that include being neglected, unloved, poor, orphaned, and almost destroyed by the madwoman in their lives. This coming of age and semi-autobiographical novel is about family, loss, forgiveness, and the power of a good book.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers

A wonderful article touching on all aspects of a memoir writer’s dilemma. I totally concur as a memoir writer myself.

This is a wonderful post about the courage it takes to be a memoir writer.