Don’t Kill Your Darlings, Set Them Free

For writers, often the most frightening advice we receive is to “kill our darlings”¾to cut loose those Hope diamonds that, while gorgeous, are sinking the boat we’re trying to steer to shore¾the beautiful opening sentence that doesn’t tie in whatsoever with the opening paragraph (or the rest of the story), the intense supporting character who wants to take over the novel, the ending that we planned when we began writing but no longer makes sense, based on what’s transpired in the previous three-hundred pages.

For writers, often the most frightening advice we receive is to “kill our darlings”¾to cut loose those Hope diamonds that, while gorgeous, are sinking the boat we’re trying to steer to shore¾the beautiful opening sentence that doesn’t tie in whatsoever with the opening paragraph (or the rest of the story), the intense supporting character who wants to take over the novel, the ending that we planned when we began writing but no longer makes sense, based on what’s transpired in the previous three-hundred pages.

Often we cling to our darlings because we lack confidence in our own abilities (“I’ll never write something so fantastic again—how could I?”). However, by doing so, we’re both challenging ourselves to create another, more beautiful darling and proving that, yes, we are capable of another darling—many more, in fact.

So they say. Between us, I’ve never actually killed my darlings. Like Walt Disney, they’re just cryogenically frozen somewhere, in my head or on my computer, waiting for the time when the technology called Jen has the ability to revive them.

Some of these darlings are only a few sentences, a few pages, an unformed impulse or image or feeling that begged to be captured, even if it didn’t know what it wanted to be, girl, boy, giraffe, or elephant. I completely believe in recycling writing—the best line from a failed story will find its way in another, or a deleted scene from an unfinished novel will be reshaped and crafted into a stand-alone short story.

But it’s not because I’m an unconfident or lazy writer: I just think there’s something else at work when we don’t kill our darlings. I’ve learned is that writing is a huge puzzle, and sometimes the answers you’re looking for don’t present themselves for years, after the fifth or sixth draft is written, after the only thing you’ve kept from the first draft is the name of the main character.

Sometimes the answers don’t even appear in the novel on which you’re working. Your imagination is a tricky, playful thing, and like a pot, it never boils while you’re watching. It’s delicious stew, something that continues its work while you’re asleep or doing other things. And sometimes when you think you’re giving up on one novel or story and starting another, you’re not really giving up at all. Instead, you’re just working on a different part of the puzzle, a blue sky at the top when for years you’ve been working on the murky, green bog at the bottom.

Then something really magical happens—you find pieces in the middle that link the blue sky to the murky green bog. Maybe it’s a cottage or a castle, or even just a road. Maybe it’s a person, or a tornado. And suddenly two completely different novels or stories have become one. You haven’t killed your darling—you’ve just let it hibernate. And you didn’t force it to stay awake—you completely forgot about it, and it woke up on its own, when you were ready for it.

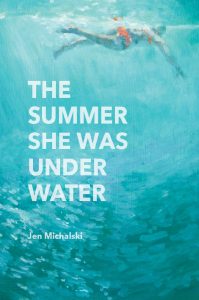

I began the novel The Summer She Was Under Water over fifteen years ago. In it, a young novelist, Sam, gets cold feet after becoming engaged to a responsible, loving, healthy boyfriend, her first (responsible, loving, and healthy, that is). She breaks off the engagement and spends the summer at the lake with her dysfunctional, blue collar family, convinced they are to blame for her brokenness. But when she is increasingly drawn to Eve, an unlikely friend she meets after getting matrimonial cold feet, she realizes that her family may not be the cause of her troubles after all.

I began the novel The Summer She Was Under Water over fifteen years ago. In it, a young novelist, Sam, gets cold feet after becoming engaged to a responsible, loving, healthy boyfriend, her first (responsible, loving, and healthy, that is). She breaks off the engagement and spends the summer at the lake with her dysfunctional, blue collar family, convinced they are to blame for her brokenness. But when she is increasingly drawn to Eve, an unlikely friend she meets after getting matrimonial cold feet, she realizes that her family may not be the cause of her troubles after all.

When I put the novel in a drawer to work on other things, it had the makings of a very standard, boilerplate coming-out novel. But the heart of the novel felt missing to me: Sam’s pain felt more searing, her strained relationship with her brother Steve more complicated, to me than her repressed sexuality. At the time, I considered the novel a failure, but refused to let it go, convinced I could recycle a few characters or mine a short story or two from it. I put it away, and in the years between, I wrote a magical realist novella, A Water Moon, about a man who finds himself pregnant. The pregnancy is actually symbolic of some heavy truths he must carry to term.

Although the structure, subject, and language were so completely different from Summer, somehow, the two projects felt connected to me. I slept on it, and when I woke up I realized I was still working on Summer the entire time. The pregnant man was Steve, Sam’s brother. And Steve was telling me what Sam couldn’t, was perhaps too ashamed, too confused to tell me: Sam wasn’t having cold feet because she was a repressed lesbian but because of something more dark, confusing, and painful. It was only coming to Summer from a different perspective that I was able to get away from its convention, from its predictable storyline, from what I was comfortable with happening.

Sometimes you find answers to your writing where you least expect them. Although I’m not saying to go through all your unfinished drafts and try to piece them together, I think that writing is a marathon, not a race, and a lot of the work is subconscious, mysterious. There are clues here, there, in your work, and one piece may not even present itself as important until you’ve written another piece, years later. So while it’s important to “kill” your darlings in one sense, don’t ever give up on them. Forget about them, but don’t quit them. Trust that the writer in you will find the answers you need—what you thought you ended years ago may only be the beginning.

—

Jen Michalski’s second novel, The Summer She Was Under Water, was published in 2016 by Queens Ferry Press. She lives in Baltimore.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Great post! I completely agree, it’s much easier to let your darlings go if you know you can keep them for a rainy day 🙂

Fabulous piece Jen! I never ‘kill’ my darlings completely either. I may kill an idea for the current story, but I hate throwing creativity away. So it’s all kept for other projects, awaiting that perfect, magical moment of resurrection!

What an insightful and wonderful article. As a psychiatrist/novelist, I really appreciate what you’ve discovered and share here. I, too, learned that the subconscious is working and making links for us. For example, when I was working on my now-published novel The End of Miracles, I had to attend to my full-time work as a psychiatrist in academia. So sometimes, when I was actively writing a particular chapter, I’d say to myself in the morning: OK, brain, I have to go to work now, but you work on this chapter in the meantime. And sure enough, many evenings when I sat down for a bit to write, just the right paragraphs came very easily and almost full-formed. Another note: my novel also has a false pregnancy central to it! I will be looking up your book next. Monica

I, too, enjoyed the piece, as it was informative, interesting and, believe it or not, something I had never actually considered, nor practiced, beforehand, even though, I must admit, it makes perfect sense, now that I see it in writing.

Yes! Reworking your darlings is a much better idea. That sentence that didn’t quite fit the mood, tone or action of one scene is still a good sentence and can find a home in another as can that slightly strange plot turn of quirky character. Nice piece – thank you.